The most prominent portrayal of demigods in recent years occurs in the American author Rick Riordan’s mythology-based middle-grade children’s books, which include the series Percy Jackson & the Olympians (published 2005 – 2009), The Heroes of Olympus (published 2010 – 2014), Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard (published 2015 – 2017), and The Trials of Apollo (published 2016 – 2020). Since Riordan’s books have an enormous fanbase and Percy Jackson & the Olympians is currently being developed into a new series for Disney+, I thought I would write this post in which I will explore how the portrayal of demigods and their powers in ancient Greek mythology and literature differs from the portrayal in Riordan’s novels.

Riordan’s novels portray demigods as having supernatural powers that correspond to specific aspects of the domains their divine parents preside over. The reality, though, is that, in actual ancient Greek and Roman sources, demigods do not typically possess any special powers or abilities that correspond in any way to the specific domain of their divine parent. Instead, what they typically inherit from their divine parent are more general exceptional qualities that correspond to the demigod in question’s gender more than their divine parentage.

Demigod men are typically said to display exceptional qualities that the Greeks and Romans considered inherently masculine, such as extraordinary physical strength and skill at fighting. Meanwhile, demigod women are typically said to display exceptional qualities that the Greeks and Romans considered inherently feminine. Notably, although both demigod men and women in general are said to possess extraordinary physical beauty, the sources tend to emphasize this aspect more for women than for men. Both demigod men and women are said in some cases to possess extraordinary cunning. By far the most important thing that makes demigods in the Greek tradition special, though, is that their divine parents look out for them and are willing to give them things they ask for.

Demigods in Rick Riordan’s novels

Before I talk about how demigods are portrayed in actual ancient Greek sources, I feel I should discuss how they are portrayed in Rick Riordan’s novels for the sake of those readers who may not have read them. The eponymous protagonist of Percy Jackson & the Olympians is Percy Jackson, who returns as one of several protagonists in The Heroes of Olympus and as a recurring character in The Trials of Apollo. In the novels, Percy is the son of Poseidon, the god of the sea, so he has special powers that are connected to the sea. For instance, he can control water in any form with his mind and talk to sea creatures.

Annabeth Chase is the deuteragonist and Percy’s main love interest in Percy Jackson & the Olympians. She returns as one of the main protagonists in The Heroes of Olympus, as a recurring character in Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard, and as a minor character in The Trials of Apollo. She is the daughter of Athena, the goddess of wisdom, strategy, war, crafts, and weaving, so she has a genius intellect, extraordinary talent at strategy, an ability to remember everything she hears, supernatural skill at weapons and fighting, extraordinary skill with mechanisms and machines, and supernatural skill at weaving.

ABOVE: Official illustrations of the characters Percy Jackson (left) and Annabeth Chase (right) by the Ukrainian artist Viktoria Ridzel (also known as Viria)

In Percy Jackson & the Olympians, Thalia Grace, who is the daughter of Zeus, the god of the sky and lightning, can summon and control lightning and electricity with her mind. She also has some ability to control the weather. In The Heroes of Olympus, her brother Jason Grace, who is the son of Jupiter, Zeus’s Roman equivalent, can also summon and control lightning and electricity and control the weather. He can also control air with his mind.

Nico di Angelo, who is a recurring character in Percy Jackson & the Olympians, one of the main protagonists in The Heroes of Olympus, and a recurring character in The Trials of Apollo, is the son of Hades, the ruler of the underworld, so he can control rocks and the earth with his mind, summon and control the dead, control bones, control shadows and darkness, control temperatures, and astral project his consciousness through dreams.

ABOVE: Official illustrations of Thalia Grace (left), Jason Grace (center), and Nico di Angelo (right) by Viktoria Ridzel

In The Heroes of Olympus, Piper McLean is the daughter of Aphrodite, the goddess of erotic desire, beauty, and sex, so she possesses the ability to cause other people to experience feelings of love and lust, effortlessly read other people’s emotions, convince other people to do whatever she tells them through supernaturally enhanced persuasion known as “charmspeak,” always appear stunningly beautiful no matter the circumstances, and speak French (the “language of love”) fluently, despite having never learned it.

Also in The Heroes of Olympus, Leo Valdez is the son of Hephaistos, the god of fire, metalworking, and craftsmanship, so he possesses supernatural knowledge of machines, has some degree of ability to influence machines with his mind, can supernaturally detect traps, can summon and control fire with his mind, and is immune to fire.

These are just a few examples of some of Riordan’s characters and their respective abilities. As you can see, the demigods in his novels possess specific divine powers closely related to the domains of their respective divine parents. Contrary to this portrayal, however, the ancient Greeks seem to have rarely ever thought of demigods as inheriting specific powers in this manner.

ABOVE: Official illustrations of Piper McLean (left) and Leo Valdez (right) by Viktoria Ridzel

A note regarding sources

Before I discuss what kinds of abilities demigods in Greek mythology have, I first must make a couple of important notes. The first of these is about sources. Two of the earliest and most important sources of information about Greek mythology are the Iliad and the Odyssey, two long ancient Greek epic poems in dactylic hexameter that are rooted in the oral poetic tradition and most likely became fixed in something resembling the form in which they have been passed down to the present day in the early-to-mid seventh century BCE.

Together, these epics are known as “Homeric” because they are traditionally attributed to a mythical poet named Homer. As I discuss in this post I wrote back in July 2019, a number of other poems were attributed to Homer in antiquity, including some which survive to the present day, but those poems are more obscure, modern scholars don’t typically refer to them as “Homeric,” and I won’t be referencing any of them in this particular post.

In addition to the Homeric epics, however, I will also be referencing other surviving ancient Greek sources, including poems by poets such as Hesiodos of Askre (who composed in dactylic hexameter and most likely flourished in around the early seventh century BCE, around the same time as the Homeric epics) and Pindaros of Thebes (lived c. 518 – c. 438 BCE).

I will also be extensively referencing various tragedies (i.e., plays about legendary people of the distant past) that were originally performed in Athens in the fifth century BCE, especially several composed by the Athenian tragic playwright Euripides (lived c. 480 – c. 406 BCE).

I have a degree in Greek and Latin and will be quoting some words and passages in Ancient Greek, but I do not expect my readers to be familiar with the Greek language and, anytime I quote material in Greek, I will provide an English translation.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons showing a Roman marble bust showing how someone imagined the mythical poet Homer might have looked, based on a Greek original of the second century BCE (left) and photograph from Wikipedia Commons of an ancient portrait bust of the Athenian tragic playwright Euripides (right)

Who actually counts as a demigod in Greek mythology?

My second prefatory note concerns the definition of the word demigod. The Greek word that is usually translated as “demigod” is ἡμίθεος (hēmítheos), which is formed from the prefix ἡμι- (hēmi-), meaning “half,” and the word θεός (theós), meaning “deity.” The word therefore literally means “half-deity.” There is, however, little to no consistency in who counts as a hēmítheos in Greek mythology.

Most people in the western world in the twenty-first century have at least some degree of familiarity with modern biology, which has established clear and consistent rules of heredity. When modern people read ancient sources, they often anachronistically project their own expectation that hereditary should work according to clear and consistent rules into the ancient sources. Ancient authors, however, did not have this expectation.

For instance, Dionysos is usually said to have been the son of Zeus and the mortal woman Semele. Based on his parentage, one would expect him to be a demigod, but, instead, he is a full Olympian god on fully equal ground with children of Zeus who have divine mothers, such as Apollon, Artemis, Hermes, etc.

By sharp contrast, in the Iliad, Sarpedon, the son of Zeus and the mortal woman Laodameia, is a mere mortal demigod—and not even an especially remarkable one at that. Although Sarpedon is characterized as a great warrior, Achilleus’s companion Patroklos, the son of two mortal parents, kills him in battle after a relatively quick fight in the Iliad 16.419–507 during his aristeia (i.e., the scene in which he has his moment of glory or best moment).

There is no clear mythical rule or explanation for why Dionysos and Sarpedon are so drastically different in power, even though they are both sons of Zeus by mortal women.

ABOVE: Detail from Wikimedia Commons of a black-figure painting by Psiax on the interior of an Attic plate dating to between c. 520 and c. 500 BCE, found at Vulci in Etruria, depicting the god Dionysos holding a kantharos of wine (left) and detail from Wikimedia Commons showing Side A of the Euphronios Krater, an Attic red-figure kalyx-krater painted by Euphronios dating to c. 515 BCE, depicting the death of Sarpedon (right)

To make matters even more confusing, there are also figures in mythology who are of purely divine ancestry, with no mortals involved, but yet who are still treated in most sources as merely mortal demigods. The most famous example of this is probably Medeia. There are several different traditions about her ancestry, but the oldest and most common tradition (which is first attested in Hesiodos of Askre’s Theogonia 956–962) holds that her father was Aiëtes, the king of Kolchis, who was the son of the god Helios and the Okeanid nymph Perseïs. Meanwhile, according to this same tradition, Medeia’s mother was the Okeanid nymph Idyia.

By ancestry alone, one would expect Medeia to be a full-blooded goddess, since both of her parents are purely divine. Hesiodos at least seems to consider her a full-blooded goddess, since he describes her marriage to the mortal hero Iason in a passage describing weddings between mortals and deities. Most ancient sources, however, including Euripides’s tragedy Medeia, first performed at the City Dionysia in Athens in 431 BCE, and Apollonios of Rhodes’s epic poem Argonautika, which he composed in the third century BCE, portray her as a mere mortal demigod.

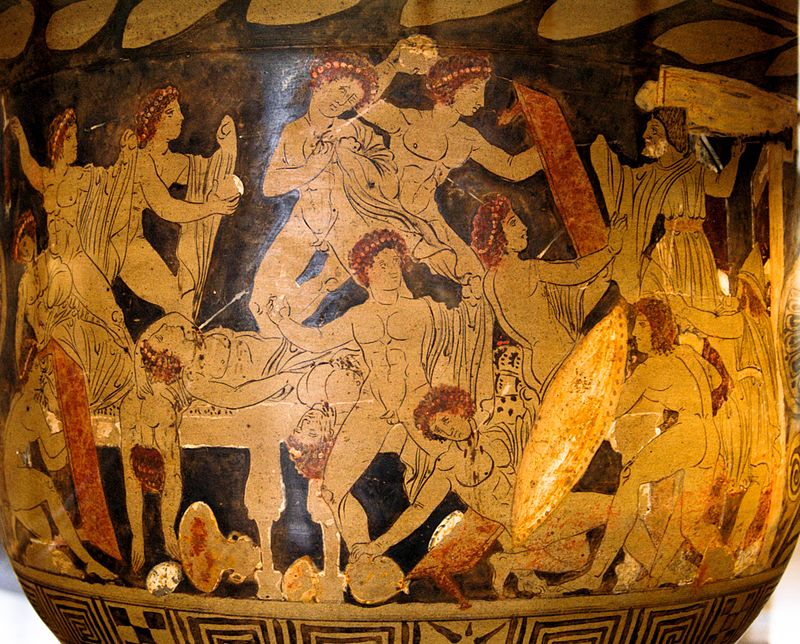

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons showing a Lucanian red-figure kalyx-krater by the Polychoros Painter dating to c. 400 BCE depicting Medeia flying away in a chariot pulled by two drakontes (i.e., giant serpents or “dragons”) while the bodies of her two sons whom she has murdered lie sprawled atop an altar on the ground

Demigod men

With those notes out of the way, let’s discuss the kinds of abilities that demigods in Greek mythology typically possess. I will start out with the men, since demigod men receive vastly greater attention in the ancient sources than the women.

In general, demigod men possess extraordinary physical beauty, extraordinary strength, and extraordinary skill at fighting. For instance, in the Iliad, Achilleus is the son of the mortal man Peleus and the goddess Thetis and he is repeatedly described as the best fighter of the Achaians. (Achaians, for those who are not familiar, is the most common name the Homeric epics use for the Greeks.)

In Book One of the poem, when Achilleus is having a bitter quarrel with Agamemnon, the commander of the Achaian army, the elderly commander Nestor intercedes in an attempt to settle the dispute (which ends up being futile). He appeals directly to Achilleus, trying to win him over in part by praising his strength, which he explicitly links with the fact that Achilleus’s mother is a goddess. He says in the Iliad 1.280–281:

“εἰ δὲ σὺ καρτερός ἐσσι θεὰ δέ σε γείνατο μήτηρ,

ἀλλ᾽ ὅ γε φέρτερός ἐστιν ἐπεὶ πλεόνεσσιν ἀνάσσει.”

This means, in my own translation:

“And, forasmuch as you are strong and a goddess mother bore you,

even so, this man [i.e., Agamemnon] at least is better, since he rules more men.”

Next, Nestor turns to address Agamemnon, but continues to praise Achilleus for his fighting ability. He says in Iliad 1.282–284:

Ἀτρεΐδη σὺ δὲ παῦε τεὸν μένος: αὐτὰρ ἔγωγε

λίσσομ᾽ Ἀχιλλῆϊ μεθέμεν χόλον, ὃς μέγα πᾶσιν

ἕρκος Ἀχαιοῖσιν πέλεται πολέμοιο κακοῖο.”

This means:

“And you, Son of Atreus, cease your anger; for I at least

beseech you to relinquish your wrath toward Achilleus, who is

a great defensive wall for all the Achaians from evil war.”

When Achilleus goes out to fight the Trojans on the field for the first time in the poem at the beginning of Book Twenty, in possibly the greatest testament to his fighting ability in the whole poem, Zeus orders all the deities to go out and aid whichever side in the battle they happen to favor. He explains this decision by saying, essentially, that no mortal is even close to being a match for Achilleus in battle and, unless the Trojans have deities on their side directly aiding them, then Achilleus may single-handedly storm the walls and sack the city of Troy all on his own before the fated time. He decrees in the Iliad 20.26–30:

“εἰ γὰρ Ἀχιλλεὺς οἶος ἐπὶ Τρώεσσι μαχεῖται

οὐδὲ μίνυνθ᾽ ἕξουσι ποδώκεα Πηλεΐωνα.

καὶ δέ τί μιν καὶ πρόσθεν ὑποτρομέεσκον ὁρῶντες:

νῦν δ᾽ ὅτε δὴ καὶ θυμὸν ἑταίρου χώεται αἰνῶς

δείδω μὴ καὶ τεῖχος ὑπέρμορον ἐξαλαπάξῃ.”

This means, in my own translation:

“For, if Achilleus alone fights against the Trojans,

then not even for a short time will they hold the swift-footed son of Peleus.

Even before this time, they were trembling even when they saw him

and now, when he indeed is raging terribly in his heart for his companion,

I fear that, even against fate, he may storm the wall.”

The other warriors in the Iliad who are sons of deities, including Sarpedon (who is the son of Zeus) and Aineias (who is the son of Aphrodite) are similarly characterized as exceptional fighters, albeit not nearly to such an extent as Achilleus.

ABOVE: Detail from Wikimedia Commons showing an ancient Greek polychrome vase painting depicting Achilleus fighting the Aithiopian king Memnon, dating to around 300 BCE or thereabouts, now held in the Rijksmuseum voor Oudheden in Leiden, The Netherlands

Men of partly divine ancestry in Greek mythology also sometimes display extraordinary cunning. In the Iliad and the Odyssey, Odysseus is a remote descendant of two major Olympian deities. His father Laërtes is the son of Arkesios, who is the son of Zeus, making Odysseus Zeus’s great-grandson. For this reason, one of Odysseus’s main epithets in the Homeric epics is διογενής (diogenḗs), which means “born of Zeus.” Meanwhile, Odysseus’s mother Antikleia is the daughter of Autolykos, who is the son of Hermes and a mortal woman whose name is usually given as Chione, thereby making Odysseus Hermes’s great-grandson as well.

In both of the Homeric epics, Odysseus is physically strong and a skilled fighter, but he is not the best fighter. Instead, his true talent lies in his ability to skillfully lie and trick his way out of messy situations and into getting whatever he wants. Perhaps no episode illustrates this more clearly than in the Odyssey, Book Nine, when Odysseus describes his encounter with the Kyklops or one-eyed giant Polyphemos, who is the son of Poseidon.

First, Odysseus and his men come ashore on a beach opposite an island that is all wilderness. Odysseus himself crosses over to the island with a company of his men to find out who the natives of the land are. They find a cave with a giant sheepfold outside it that is made of slabs of stone between great tree trunks and full of sheep and goats.

Odysseus goes into the cave, bringing his twelve best fighters and a flask of the finest wine with him. They find that no one is in the cave when they go in, so they start a fire, eat some of the cheese they find, and wait for the owner to return. When Polyphemos, the owner of the cave, finally returns, he immediately seals the entrance to the cave shut with a giant slab of stone. When he sees Odysseus and his men, he immediately demands to know who they are and where they are from.

Odysseus tells him that they are Achaians who served under Agamemnon who have come from Troy and that Polyphemos should treat them well, since Zeus will punish the host who mistreats his guests. Polyphemos scoffs at this; he says that the Kyklopes care nothing about Zeus or any of the other deities and demands to know where Odysseus’s ship is. Odysseus lies, telling him that the ship has been wrecked and the men who are there in the cave are the only survivors (Od. 9.282–286). Upon hearing this, Polyphemos reaches down, grabs two of Odysseus’s companions, bashes their brains out on the cave floor, dismembers them, and eats them raw (Od. 9.287–298).

Trapped in the cave, Odysseus formulates a plan to escape. First, when Polyphemos leaves the cave and seals the entrance behind him, trapping Odysseus and his men inside alone, they fashion a long pole they find in the cave into a weapon by sharpening the end to a point and then hide it in a pile of dung in a corner of the cave (Od. 9.318–330). When Polyphemos returns to the cave, he kills and eats two more of Odysseus’s men. Odysseus offers him the wine he brought with him into the cave (Od. 9.344–352). Polyphemos drinks all the wine in one gulp (Od. 9.353–354). He asks Odysseus’s name, promising to give him a gift in return if he tells him (Od. 9.355–359).

Odysseus replies (Od. 9.363–367) that his name is Οὖτις (Oûtis), which means “No One.” As I note in the post I wrote about the Kyklops episode way back in May 2019, this name is a pun, because another way to say “No One” in Ancient Greek is μήτις (mḗtis), which sounds exactly like the word μῆτις (mêtis), which means “cunning.” Upon hearing this, Polyphemos reveals to Odysseus his gift: a promise that he will eat him last, after all his companions (Od. 9.368–370). Then, drunk from all the wine, he falls over, fast asleep, hiccupping and drooling wine and bits of human flesh (Od. 9.371–374).

As soon as Polyphemos is sleep, Odysseus takes the sharpened pole, chars it in the embers of the fire and, with the aid of his men, plunges it into the Kyklops’s single eye (Od. 9.375–414). Waking up, Polyphemos tears the pole out of his eye and lets out a cry of pain that brings the other Kyklopes to the cave to ask why he is screaming (Od. 9.395–406). Polyphemos replies that “No One” is trying to kill him, so the other Kyklopes, who are apparently not especially bright, assume he must be fine and leave (Od. 9.407–414).

With Polyphemos now blinded, Odysseus and his men are able to escape the cave by clinging to the underbellies of Polyphemos’s sheep. When the Kyklops opens the cave to let his sheep out, he touches each one on the back as it leaves to make sure it is really a sheep and there is no one riding it, but he neglects to touch their underbellies and therefore fails to notice the men who are clinging underneath.

ABOVE: Detail from Wikimedia Commons showing the neck of the “Eleusis Aphora,” a proto-Attic funerary amphora dating to around 660 BCE, depicting Odysseus and his men plunging a sharpened stake into the eye of the Kyklops Polyphemos, blinding him, now held in the Archaeological Museum of Eleusis

Demigod women

There are far fewer demigod women in Greek mythology than demigod men and they tend to receive much less attention in the sources, but they are generally said to possess extraordinary physical beauty. The most famous demigoddess in Greek mythology and literature is most likely Helene of Sparta. She is said to have been the daughter of Zeus and the mortal woman Leda, who was the daughter of King Thestios of Thessalia and the wife of King Tyndareus of Sparta.

Helene is renowned in the ancient sources for having supposedly been the most beautiful mortal woman who ever lived. As I discuss in this post I wrote back in August 2019, ancient written sources and artistic depictions show no consistency concerning any specific detail of her appearance, but they do all agree in describing or depicting her as extraordinarily beautiful.

In Book Three of the Iliad, the goddess Iris coaxes Helene to go up onto the walls of Troy to view the battlefield from above the Skaian gates with King Priamos and the elder men of Troy. These elder men have undoubtedly seen Helene before, but, when she appears, her beauty instantly stuns them nonetheless. In fact, when they see her, the men say that they cannot blame the Trojans and Achaians for fighting and dying in this long and bloody war just for her, since she looks “terrifyingly” just like a goddess. They say to each other, in the Iliad 3.156–158:

“οὐ νέμεσις Τρῶας καὶ ἐϋκνήμιδας Ἀχαιοὺς

τοιῇδ᾽ ἀμφὶ γυναικὶ πολὺν χρόνον ἄλγεα πάσχειν:

αἰνῶς ἀθανάτῃσι θεῇς εἰς ὦπα ἔοικεν:”

This means, in my own translation:

“It is no blame that the Trojans and well-greaved Achaians

on account of such a woman have for such a long time suffered pains;

she is terrifyingly just like the immortal goddesses for the eye.”

This passage magnificently drives home the point that Helene, as the literal daughter of Zeus, has enough of the divine in her that she is actually dangerous, and it is terrifying merely to stand in her presence. She is dangerous and terrifying not because she has inherited her father’s ability to hurl lightning bolts, but rather because she physically looks just like a goddess.

ABOVE: Lithograph illustration by the English illustrator Walter Crane (lived 1845 – 1915) for the book The Story of Greece: Told to Boys and Girls by Mary MacGregor, showing what he imagined Helene might have looked like standing on the walls of Troy

Demigod women can also sometimes display extraordinary cunning, much like demigod men. Notably, Odysseus’s wife Penelope is said to have been the daughter of King Ikarios of Sparta and his wife, the naiad Periboia. In the Odyssey, she embodies the role of the ideal wife. She remains loyal to Odysseus and does not remarry to another man in his absence, even though it has been twenty years since she last saw him, she believes that he is dead, and over a hundred suitors are at Odysseus’s home clamoring to marry her. Instead, she uses her exceptional cunning to avoid marrying any of the suitors as long as possible, devising clever tricks to buy herself time.

The story of Penelope’s most famous trick is told not only once, but three different times in the Odyssey with almost the exact same wording each time (Od. 2.93–110, 19.137–156, and 24.129–148). The story goes that Penelope promised the suitors that she would pick one of them to marry only once she had finished weaving a burial shroud for Odysseus’s father Laërtes (who, at the time the Odyssey takes place, is still alive, but very elderly) in anticipation of his death and funeral.

But all of this was a trick. She would weave the shroud during the day while other people were watching, but then, each night, when she was alone, she would secretly undo her own weaving so that the shroud would never be finished. She is supposed to have held off the suitors for three years in this manner. Eventually, though, her enslaved handmaid Melantho happened to catch her one night undoing her weaving and she revealed her mistress’s clever subterfuge to her lover Eurymachos, one of the suitors.

ABOVE: Penelope and the Suitors, painted by the English Pre-Raphaelite painter John William Waterhouse between 1911 and 1912

Later, in Book Twenty-One, Penelope introduces a contest to decide which of the suitors she will marry. First, she brings out Odysseus’s old bow, which Iphitos, the son of Eurytos, gave to him and which she knows no person other than Odysseus himself can string (Od. 21.1–66). Then she declares that she will marry the suitor who is best able to string the bow, notch and draw an arrow, and shoot the arrow “through” twelve iron axes (Od. 21.67–79).

As the New Zealand classicist Peter Gainsford discusses in this post he wrote on his blog Kiwi Hellenist in September 2019, it is unclear what exactly the Odyssey is describing when it talks about shooting an arrow “through” twelve axes. There are four different scholarly interpretations of this part of the challenge. One interpretation holds that the axes are standing upright with the axeheads in the air, that the axeheads are intricately shaped and have some sort of gaps or holes in them, and that the challenge is to shoot an arrow through these gaps or holes.

A different interpretation holds that the axes are all upside-down, with the axeheads toward the ground and the handles sticking up in the air, and that the challenge is to shoot an arrow through the hanging rings on the butt ends of the handles. A third interpretation holds that the axeheads have been removed from their shafts and have been set up with the blades sticking in the ground and that the challenge is to shoot an arrow through the sockets of the axeheads that the shafts would normally go through.

The interpretation that Gainsford and I both strongly favor, though, is that the axes are standing upright and that the challenge is to fire an arrow so powerful that it literally pierces and passes through twelve solid iron axeheads in succession. This would, of course, be physically impossible for someone to do in real life, since an arrow cannot pierce through an iron axehead at all, let alone through twelve of them. Nonetheless, this reading takes the Odyssey’s description of the challenge at its most literal meaning. The Greek text of the Odyssey makes no unambiguous mention of any holes, hanging rings, or sockets. Instead, the Greek phrase that it uses (at Od. 21.328) is “διὰ . . . σιδήρου,” which literally means “through the iron.”

Furthermore, the physical impossibility of the task actually makes sense if we interpret the test of the bow as another one of Penelope’s tricks to avoid marrying any of the suitors. In other words, according to this interpretation, Penelope is intentionally giving the suitors a challenge that she knows from the beginning will be impossible for any of them to accomplish.

ABOVE: Engraved illustration made by the English engraver Robert Hartley Cromek for an 1806 edition of Alexander Pope’s English translation of the Odyssey, based on an earlier painting by the Swiss artist Henri Fuseli (lived 1741 – 1825)

All the suitors take turns attempting the challenge, but not a single one of them is even able to string Odysseus’s great bow. Then Odysseus himself, whom Athena has miraculously disguised as an elderly beggar, comes forward and asks to have a turn (Od. 21.273–284). The suitors are furious at his audacity to even suggest that he might participate and Antinoös, the cruelest and most unpleasant of the suitors, scolds him (Od. 21.274–310).

Despite their objections, though, Penelope (who may or may not have secretly figured out by this point that the beggar is actually her husband) and Odysseus’s son Telemachos (who definitely knows that the beggar is really his father, since Odysseus has told him and he is in on the plan) both speak out in his favor and they give Odysseus a turn (Od. 21.311–353).

The suitors mock Odysseus as he takes up the bow in preparation. Nonetheless, he, being the superhuman demigod he is, easily strings it, notches and draws back an arrow, and shoots it straight through all twelve axes without even bothering to stand up from his seat (Od. 21.392–423). The suitors are all stunned.

As Odysseus rises from his seat, Athena restores to him his natural appearance, revealing his true identity. Then, in the epic climax, Odysseus, Telemachos, and two of Odysseus’s loyal slaves—the swineherd Eumaios and the cowherd Philoitios—mercilessly slaughter all the suitors in the hall in a bloody massacre.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons showing Side A of a Campanian red-figure bell-krater by the Ixion Painter dating to c. 330 BCE depicting Odysseus, Telemachos, and Eumaios slaughtering the suitors of Penelope, now held in the Louvre Museum in Paris

Medeia is an interesting example of a demigod woman who possesses special abilities, but ones that seemingly have nothing to do with her specific divine ancestors. Her paternal grandfather is Helios, the sun-god, and her paternal grandmother and mother are both Okeanid nymphs, so, based on the logic of demigod powers in Rick Riordan’s novels, someone might expect her to have sun and ocean powers. Instead, she has the power of spells and potions.

It is not clear how Medeia came to possess her magic powers. One possibility is that she has inherited them from her divine ancestors and therefore possesses them innately. Another possibility is that they are powers that anyone can learn and she has acquired them from having studied magic for many years and mastered it. A third possibility is that she has acquired them through some combination of natural aptitude as a result of her ancestry and personal study.

In any case, Medeia is absolutely ruthless in her willingness to murder basically anyone to get what she wants. The historian Pherekydes of Athens (fl. c. 465 BCE) in a fragment (FGrHist 3.F.32a–c = EGM 32a–c) and Euripides in his tragedy Medeia (lines 167 and 1334) both reference the story that, when Iason and Medeia were fleeing her homeland of Kolchis after stealing the Golden Fleece from her father Aiëtes, she murdered her own brother Apsyrtos, chopped up his body, and scattered the pieces in the sea behind Iason’s ship the Argo to slow down her father’s ship as he pursued them, knowing that he would stop to collect the chopped up pieces of his murdered son’s body.

Another myth that is referenced by several Classical Greek authors, including the poet Pindaros of Thebes in his Pythian Ode 4.250, Pherekydes of Athens in a fragment (FGrHist 3.F.105 = EGM 105), and Euripides in his Medeia (lines 9, 486–487, and 504–508), holds that, when Medeia returned with her lover Iason from her own homeland of Kolchis to his homeland of Iolkos, it was still ruled by his uncle Pelias, who had usurped the throne from his half-brother, Iason’s father Aigias, and who refused to return the throne to Iason as its rightful heir.

Medeia therefore devised a clever plot to get rid of Pelias. First, she showed Pelias’s daughters how she could miraculously make an old ram young again by chopping it to pieces and throwing the pieces into a boiling cauldron that she had filled with magic herbs. The ram sprang forth from the cauldron as a rejuvenated young kid.

Having seen this, Pelias’s daughters attempted to use the same trick to make their aging father young again. They chopped him up and threw his pieces into a boiling cauldron. This time, however, Medeia did not give them the magic herbs needed to complete the spell, so Pelias remained dead and did not spring out from the cauldron rejuvenated like the ram. Thus, Medeia tricked Pelias’s own daughters into killing him.

ABOVE: Illustration from 1894 by Dugald Sutherland MacColl after a scene from an Attic black-figure amphora from Etruria, depicting the ram rising from the cauldron rejuvenated, now held in the collection of the British Museum

In Euripides’s tragedy Medeia, Medeia and Iason have married, she has given birth to two sons, and they are living in the city of Corinth, but Iason has recently betrayed and divorced Medeia in order to marry Kreusa, the daughter of Kreon, who is the king of Corinth (Med. 16–45). Kreon declares that Medeia is banished from Corinth forever and must take the two sons she has had with Iason with her in her exile (Med. 271–276). Medeia begs him to let her stay in Corinth just one more day (Med. 340–347) and Kreon reluctantly agrees (Med. 348–356).

Medeia immediately begins plotting to use the single day she has been granted to make Iason suffer the most (Med. 364–409). She sends her two sons to deliver a beautiful dress and golden headband to Kreusa as marriage gifts for her wedding to Iason (Med. 1136–1155). Kreusa eagerly puts on the dress and the headband, not knowing that Medeia has secretly covered them in an invisible deadly poison (Med. 1156–1166).

Suddenly, her skin changes color, white foam bubbles from her mouth, her eyes roll back in their sockets, the headband catches fire, the gifts become stuck to her body so she cannot remove them, her skin melts off, she dies a horrifying and torturous death, and her corpse is so horribly disfigured that she is no longer even recognizable from her appearance (Med. 1167–1203).

Kreon, the girl’s father, enters the room, sees her corpse lying on the ground, and immediately rushes to embrace her and kiss her, but, when he does, he finds himself stuck to her dress (Med. 1204–1214). He struggles to extricate himself, but all his efforts are in vain and he too dies a horrifying and torturous death from Medeia’s poison (Med. 1215–1221).

But Medeia does not stop here. She murders both of her own sons in order to cause Iason even more pain by depriving him of heirs (Med. 1236–1317). Iason confronts her and then she escapes with her sons’ bodies in a flying chariot pulled by two drakontes, or giant serpents (Med. 1318–1419). She flees to Athens, where King Aigeus has already promised her sanctuary.

This story demonstrates Medeia’s extraordinary cleverness, her ability to use spells and potions, and her ability to wreak devastating vengeance upon anyone who dares to cross her.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of Side A of a Campanian red-figure neck amphora by the Ixion Painter dating to c. 330 BCE, discovered at Kyme, depicting Medeia murdering one of her own sons, now held in the Louvre Museum in Paris

Deities protecting and aiding their demigod offspring

One of the most important abilities that demigods in Greek literature possess actually has nothing to do with their own innate abilities; instead, it is the fact that their divine parents look out for them and are willing to grant them extraordinary favors. In Rick Riordan’s novels, the deities more-or-less ignore their children and don’t really look out for them, but, in actual ancient Greek literature, it is precisely the fact that deities do look out for their own children that makes demigods so dangerous to mess with.

The whole plot of the Iliad sets into motion in Book One when Chryses, the Trojan priest of Apollon, begs Agamemnon to return his daughter Chryseïs, whom the Achaians have captured and whom Agamemnon is keeping as his slave, offering to pay splendid ransoms for her return.

When Agamemnon angrily refuses and insults Chryses, the priest prays to Apollon to unleash his wrath upon the Achaians. Apollon rains down his arrows of plague upon the Achaian army and, at Achilleus’s behest, the Achaian leaders consult the seer Kalchas, who informs them that Agamemnon must return Chryseïs in order for the plague to end.

Agamemnon, angry that Apollon is forcing him to return Chryseïs, takes Briseïs, the woman Achilleus is keeping as his slave, as his own. Achilleus, absolutely enraged over this, declares that he will no longer fight for the Achaians, nor will any of the Myrmidons, the soldiers under his command.

Furthermore, he begs his goddess mother Thetis to call in a favor with Zeus to give the Trojans the upper hand and cause the Achaians to suffer and die until Agamemnon agrees to apologize and return Briseïs. Thetis goes to Zeus and begs him to grant this favor for her son and Zeus gives his nod of assent. Thus, the Iliad only unfolds the way it does because Thetis is willing to call in personal favors with the other deities to help her son.

ABOVE: Thetis and Zeus, painted by the Ukrainian Neoclassical painter Anton Losenko (lived 1737 – 1773)

The other Achaian characters in the epic also perceive Achilleus as possibly having greater knowledge of the divine than they do themselves because of his goddess mother. Notably, Patroklos suspects at one point that Thetis may have told Achilleus some “θεοπροπία . . . πὰρ Ζηνὸς” (“divine prophecy . . . from Zeus”) that the other Achaians do not know (Il. 16.36–37).

After Patroklos dies and Hektor strips Achilleus’s armor from his corpse, Thetis calls in a favor with Hephaistos to persuade him to make a new shield and suit of armor for Achilleus (Il. 18.368–617). The divinely wrought armor is so spectacular that Achilleus himself is the only mortal character who is able to gaze directly upon it (Il. 19.12–19).

Later, when Achilleus is grieving for Patroklos, he adamantly refuses to eat or drink any mortal sustenance (Il. 19.205–214 and 319–320), so Zeus orders Athena to secretly put ambrosia and nektar—the food and drink of the deities—in him to nurture him (Il. 19.340–351).

ABOVE: Detail from Wikimedia Commons of an Attic black-figure hydria dating to between c. 575 and c. 550 BCE depicting Thetis delivering the new armor forged by Hephaistos to her son Achilleus

In the Iliad, Aineias is the son of the goddess Aphrodite and the mortal Dardanian prince Anchises. The Iliad describes no less than three separate occasions in which Aineias finds himself in danger and deities quickly swoop in to rescue him.

First, in Book Five, the Achaian warrior Diomedes lifts up an enormous boulder, severely wounds Aineias, and is about to kill him (Il. 5.302–310), but then Aphrodite, sensing that her son is in danger, appears out of nowhere (Il. 5.311–313). She swiftly grabs Aineias, wraps her dress around him to shield him from Diomedes, and carries him away (Il. 5.314–318). Diomedes chases after her and manages to cut her hand with the tip of his spear. Shrieking in pain, she drops Aineias, but Apollon catches him and protects him in his arms with a cloud of dust (Il. 5.343–346).

Later, in Book Twenty, Aineias confronts Achilleus. Achilleus taunts him saying that he attacked Aineias once before, but Zeus and the other deities rescued him, and says he does not think they will rescue him this time (Il. 20.178–198). They fight. Then, when Achilleus is right about to kill Aineias, Poseidon takes notice (Il. 20.288–292).

Poseidon summons a cloud of mist, removes Achilleus’s spear from Aineias’s shield, grabs Aineias, and flies with him over the men fighting, removing him to the furthest edge of the battlefield (Il. 20.318–329). Once they have reached safety, Poseidon scolds Aineias for his reckless bravery in trying to fight Achilleus (Il. 20.330–340). When the mist clears and Achilleus sees that Aineias is gone, he expresses his astonishment at just how beloved Aineias must be to the deities (Il. 20.341–352).

Elsewhere in the Iliad, when Patroklos is about to kill Sarpedon, Zeus desperately wants to intervene to save his son (Il. 16.431–338). The only reason he stops himself is because Hera warns him that it would go against Fate, that the other deities would not approve, and that it would lead other deities to rescue their sons from combat when it was fated for them to die, which would result in chaos (Il. 16.439–461).

ABOVE: Detail from an Attic red-figure krater dating to between c. 490 and c. 480 BCE depicting Diomedes (the warrior on the center-left) aided by Athena (behind him on the far left) attacking Aineias (the warrior on the center-right) as Aphrodite swoops in on the far right to rescue her son

In the Odyssey, right after Odysseus and his men have escaped from Polyphemos, as they are sailing away, Odysseus foolishly shouts his real name to the Kyklops on the shore in an act of hubris (Od. 9.502–505). Polyphemos, in turn, blindly hurls immense boulders in the direction of Odysseus’s ship. Then he prays to his divine father Poseidon and begs him to ensure that Odysseus will never return home or, if it is fated that he must return home, ensure that he will only do so after many long years of pain and suffering, after losing all his men, and making his return journey under a foreign sail to find his home in disorder (Od. 9.526–535).

Odysseus claims that Polyphemos’s curse is the reason why he is forced to spend years trapped at sea, unable to return home. Thus, we see that, despite all Polyphemos’s own strength, what ultimately causes Odysseus the most suffering is the fact that Poseidon listens to his son’s prayer and goes to great lengths to ensure that Odysseus only returns home after many years of suffering.

ABOVE: Painting made by the Italian Baroque painter Guido Reni between 1639 and 1640 depicting the blinded Polyphemos lifting a boulder to hurl at Odysseus’s ship as he sails away

In Euripides’s tragedy Hippolytos, which was first performed at the City Dionysia in Athens in 429 BCE, Theseus, the king of Athens, is the son of Poseidon. He has a wife named Phaidra and an illegitimate son named Hippolytos. Hippolytos spurns erotic attraction, despises all women with a fiery hatred, and refuses to pay due respect to the goddess Aphrodite. Instead, he only worships Artemis, the virgin goddess of the hunt.

Aphrodite, seeking to punish Hippolytos for his refusal to pay her the proper respect, causes Phaidra to lust madly after him. Phaidra tries to resist her longing for Hippolytos and is determined to starve herself so that she will not act on her shameful desire and bring dishonor to her husband. Nonetheless, she confesses her longing for Hippolytos to her nurse. The nurse tells Phaidra that she can make a potion for her that will cure her longing (Hip. 433–481).

Then, without Phaidra’s permission, the nurse goes to Hippolytos, tells him that Phaidra sexually desires him, and encourages him to return her affections. Hippolytos is absolutely shocked and disgusted and delivers a full-on misogynistic tirade (Hip. 616–668), in which he denounces and curses all women, but Phaidra and her nurse especially, and declares that he will tell Theseus about Phaidra’s lust for him at the soonest possible opportunity.

Phaidra overhears the conversation between Hippolytos and the nurse and hangs herself (Hip. 669–789). Theseus returns to find Phaidra’s body with a wax tablet tied to her hand with a suicide note written on it (presumably by either Phaidra herself or the nurse) claiming that she killed herself because Hippolytos raped her (Hip. 790–886). Theseus, horrified, prays to his father Poseidon and begs him to kill Hippolytos. He declares, in lines 887–890:

“ἀλλ᾽, ὦ πάτερ Πόσειδον, ἃς ἐμοί ποτε

ἀρὰς ὑπέσχου τρεῖς, μιᾷ κατέργασαι

τούτων ἐμὸν παῖδ᾽, ἡμέραν δὲ μὴ φύγοι

τήνδ᾽, εἴπερ ἡμῖν ὤπασας σαφεῖς ἀράς.”

This means, in my translation:

“But, oh father Poseidon, those three curses

which you once promised to me, fulfill one

of them: my son. And let him not flee this present day

if truly you bestowed to me distinct curses.”

Hippolytos comes in right after this to see Phaidra’s body. He emphatically denies that he ever raped Phaidra (Hip. 983–1035), but Theseus, disbelieving him, banishes him from the city forever. Hippolytos gets in his chariot to ride away. Then, as he is riding past the shore, an enormous wave rises up and an immense bull rises from it (Hip. 1205–1214). The bull gives a loud bellow (Hip. 1215–1217), instantly causing Hippolytos’s horses to panic and run in the opposite direction (Hip. 1218).

Hippolytos manages to keep control at first, but then the bull appears again, charging from the other direction, and the horses run the other way, with the bull keeping pace until the chariot flips over on some rocks (Hip. 1219–1233). Hippolytos, tangled in the reins, is dragged along by the horses (Hip. 1234–1237). His head smashes upon on a rock, his flesh is shredded, and he dies a horrifying death in pain and agony (Hip. 1238–1239). In the final scene of the play, Theseus finds his son dying on the beach. Artemis reveals to Theseus the truth and swears that she will obtain vengeance against Aphrodite for what she has done to her favorite mortal.

In the play, Theseus has no special powers of his own; instead, his power comes from the fact that Poseidon is willing to listen to him and heed his prayers because he is his son. Hippolytos’s grisly demise is only possible because Poseidon heeds Theseus’s complaint.

ABOVE: Roman fresco from the city of Herculaneum dating to the first century CE depicting Phaidra (left), the nurse (center), and Hippolytos (right), now held in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples

Examples of demigods who do display abilities associated with their divine parents

There are a few examples of demigods in Greek mythology who display special abilities associated with their divine parents’ specific domains—but, in every case that I am aware of except one, the sources are unambiguous that the demigod in question received their abilities from their divine parent as a gift and did not inherit those abilities naturally.

I will start out with the one exception that I can think of, which is the demigod Asklepios, who is said to have been the son of Apollon, the god of plague, medicine, and healing, and the mortal woman Koronis. Asklepios is said to have possessed supernatural skill at medicine, which he used to save the lives of many people who were near death. He is even said to have been able to bring the dead back to life. The Greek historian Diodoros Sikeliotes (lived c. 90 – c. 30 BCE) writes the following in his Library of History 4.71.1, as translated by C. H. Oldfather, with some edits of my own:

“Now that we have examined these matters we shall endeavour to set forth the facts concerning Asklepios and his descendants. This, then, is what the myths relate: Asklepios was the son of Apollon and Koronis, and since he excelled in natural ability and sagacity of mind, he devoted himself to the science of healing and made many discoveries which contribute to the health of mankind. And so far did he advance along the road of fame that, to the amazement of all, he healed many sick whose lives had been despaired of, and for this reason it was believed that he had brought back to life many who had died.”

Diodoros Sikeliotes presents Asklepios’s skill as a physician as resulting from a combination of his own natural talent that he inherited from his divine father and his dedication to the study of medicine. Heredity is certainly not the only factor in this story, but it does seem to be a factor.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons showing a Roman marble statue of the medicine god Asklepios dating to the early third century CE

The legendary thief Autolykos, the maternal grandfather of Odysseus, is said to have been the son of Hermes, the god of thieves, and a mortal woman who, according to the most common version of the story, was named Chione. The Roman writer Pseudo-Hyginus, who most likely wrote sometime around the second century CE or thereabouts, records in his Fabulae 201 that Hermes gave Autolykos the ability to steal anything and never be caught and the ability to shapeshift from one form to another. He writes, as translated by R. Scott Smith, with some minor edits of my own:

“Mercurius [i.e., the god the Romans equated with Hermes] endowed Autolycus, his son by Chione, with the gift of being the most thievish of all men and never being caught doing a theft. So that he could steal anything, Mercurius gave him the power to change into whatever appearance he wished: from white to black or black to white, from having horns to not having them, and back again.”

Notice that, unlike Diodoros Sikeliotes with Asklepios, Pseudo-Hyginus clearly presents Autolykos’s abilities as something his father gave him as a gift, rather than any kind of innate ability that he inherited on his own.

Interestingly, these kinds of stories do not just occur in mythology. The Greek philosopher Herakleides Pontikos (lived c. 390 – c. 310 BCE) apparently told a story in one of his works that the philosopher Pythagoras of Samos (lived c. 570 – c. 495 BCE) had claimed that, in one of his past lives, he had been a son of Hermes named Aithalides and that his father had granted him the ability to always remember all his previous incarnations.

Sadly, Herakleides Pontikos’s work in which he told this story has not survived to the present day, but the later Greek biographer Diogenes Laërtios, who flourished in around the third century CE or thereabouts, preserves the story through summary in his work The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 8.1.4–5. He writes, as translated by R. D. Hicks, with some edits of my own:

“This is what Herakleides Pontikos tells us he used to say about himself: that he had once been Aithalides and was accounted to be Hermes’s son, and Hermes told him he might choose any gift he liked except immortality; so he asked to retain through life and through death a memory of his experiences. Hence in life he could recall everything, and when he died he still kept the same memories. Afterwards in course of time his soul entered into Euphorbos and he was wounded by Menelaos.”

“Now Euphorbos used to say that he had once been Aithalides and obtained this gift from Hermes, and then he told of the wanderings of his soul, how it migrated hither and thither, into how many plants and animals it had come, and all that it underwent in Hades, and all that the other souls there have to endure.”

“When Euphorbos died, his soul passed into Hermotimos, and he also, wishing to authenticate the story, went up to the temple of Apollon at Branchidai, where he identified the shield which Menelaos, on his voyage home from Troy, had dedicated to Apollon, so he said : the shield being now so rotten through and through that the ivory facing only was left.”

“When Hermotimos died, he became Pyrrhos, a fisherman of Delos, and again he remembered everything, how he was first Aithalides, then Euphorbos, then Hermotimos, and then Pyrrhos. But when Pyrrhos died, he became Pythagoras, and still remembered all the facts mentioned.”

It is impossible to say whether this story really goes all the way back to Pythagoras himself, since Herakleides Pontikos was writing well over a century after his death. In any case, it serves as a kind of origin myth for how Pythagoras supposedly knew about μετεμψύχωσις (metempsýchōsis) or the transmigration and reincarnation of souls, which was an important Pythagorean teaching.

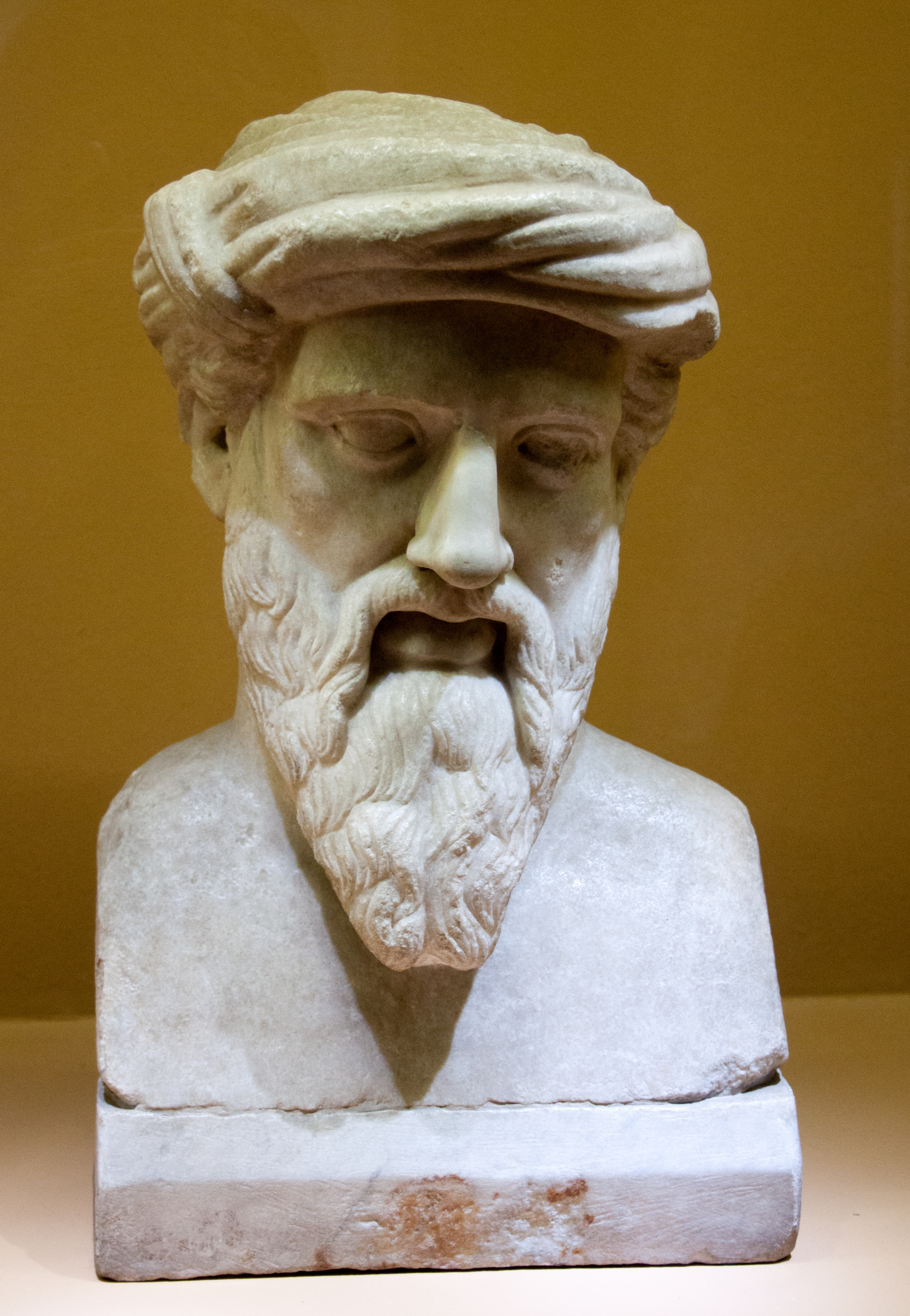

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons showing a Roman marble bust dating to the first or second century CE intended to represent the Greek philosopher Pythagoras of Samos, based on an earlier Greek original, now held in the Musei Capitolini in Rome

Conclusion

To circle back around to the where we started, the portrayal of demigods in Rick Riordan’s novels is generally not reflective of the portrayal of demigods in Greek mythology. Instead, the demigods in Riordan’s novels more closely resemble modern superheroes.

The powers they possess (such as the power to control water with one’s mind, the power to control lightning, the power to raise and control the dead, the power to summon and control fire, etc.) are much more along the lines of the kind of superpowers that one might expect a character to have in a Marvel movie than the more general kind of exceptional qualities one would expect for a demigod in a work of ancient Greek literature.

This does not, however, mean that Riordan’s novels are “wrong” or that he has necessarily misunderstood Greek myths. His novels are specifically intended as modern, American reinterpretations of ancient stories, so it makes sense that he has modernized and Americanized the kinds of powers that demigods have. I am writing this post not so much to “correct” Riordan and more to give people who may have grown up reading his novels like I did or who may have read them with their children a resource about some of the ways he departs from the Greek sources and what the Greek sources actually say.

There are also some interesting evidence that hints to there being demigods in the Bible. For example the brief passage in Genesis 6:1-4 that talks of the sons of God (i.e. Elohim; which can be used as its original plural meaning for gods or simply a generic name for God) having sexual relations with the daughters of mortals and giving rise to the Nephilim, described as “the heroes that were of old, warriors of renown.” I recommend checking this article that goes into a little more detail about them: https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/hebrew-bible/who-are-the-nephilim/

Some figures in the Bible also act not too similar from demigods, the biblical judge Samson comes for example to mind. Even though he’s not of divine parentage (though who knows if this was originally the case or simply editing by Deuteronomic Historical editors), some of his actions are comparable to Greek heroes like Heracles or Perseus, like killing a thousand Philistines with nothing but the jawbone of a donkey.

Yes, I am quite well aware of both the Nephilim and Samson. In fact, I actually have a post that I will probably make sometime very soon in which I will discuss the Nephilim in particular in some detail. Nonetheless, I thank you for sharing these examples here for anyone who might be reading the comments who may not have already heard of them.

I’m a bit of a Bible nerd.

So am I.

Plato might also be relevant here. Diogenes Laertius reports a story where his father was actually Apollo rather than the mortal Ariston. Presumably the people who came up with this story assumed some qualities of the divine parent would be inherited by their child, since they picked a god associated with knowledge as the great philosopher’s true father.

Ah yes! I forgot about that. That is a good example.

Also, although the oldest surviving sources that mention Orpheus identify him as the son of the Thrakian king Oiagros, some later sources identify him as the son of Apollon.

That was very interesting thanks. In fact, regarding innate abilities versus learned or gifted ones I’ve heard that Greece is the first place you have the idea magic didn’t come from the gods (e.g. not having to beg them for new spells). Do you know if that’s true?

I must admit that I haven’t heard that claim before. I strongly suspect that it is incorrect, but I cannot think of any sources off the top of my head to disprove it.

Wait — Athena has a daughter??!

I had to stop there and be very surprised. Already it prejudices me against these stories.

Riordan’s novels have an explanation for it, which is that Athena can miraculously produce children through her mind, without participating in any kind of sexual relations. Thus, according to the novels, she is able to have children while still remaining a perpetual virgin.

Pyhtagoras’ story leads me to ask – did the Greeks, and the people of the pre-christian mediterranean in general, believe in re-incarnation? I had thought that generally, the western world (including the “near east”) had always believed in an eternal afterlife – whether Ancient Egyptain, Greek, Roman, Norse or Christian, and that re-incarnation was more of an eastern concept, as it is prominent in the dharmic traditions and to this day.

Some Greeks did believe in reincarnation. This is said by Herodotos (2.123.3), without specifying what were their names. The Pythagoreans certainly believed this, as is attested by one of the surviving fragments of Xenophanes (21 B 7 Diels-Kranz, apud Diogenes Laertios, 8.36), and it’s very likely that the historian was thinking of them; but it was also taught by Empedokles (see e. g. fragment 31 B 117 DK) and others. Herodotos (2.123.2) thought wrongly that this doctrine was learned by the Greeks from the Egyptians.

I truly can’t express how happy it makes me feel when I get such well-informed commenters!

I’m sure you can’t be happier than me when I read a new article from your blog. 😀

Aw! Thank you so much!

Don’t the Platonic dialogues show Socrates believed that reincarnation occurred? I heard he was influenced by the Pathagoreans somewhere-I’m not sure if that’s true. Since Greeks were in contact with Indians I hear, maybe the idea came from India to Greece over time?

Thanks Nic!

Nicolás’s comment above is absolutely correct. Many different beliefs about what happens to a person’s soul after they die coexisted in ancient Greece. The most common view, of course, was that, after a person dies, their soul goes to the Underworld and remains there forever, but there were also ancient Greek people who believed other things about what happens after a person dies, including many who believed in μετεμψύχωσις (metempsýchōsis) or reincarnation.

Metempsychosis is a doctrine that is especially closely associated with Pythagoras of Samos, his followers, and those who later claimed to have been influenced by his teachings. The pre-Socratic philosopher and elegiac poet Xenophanes of Kolophon (lived c. 570 – c. 478 BCE) was a contemporary of Pythagoras and there is a strong likelihood that he actually met Pythagoras in person or at least saw him at some point, since they were both Ionians who settled in southern Italy and most likely travelled in the same circles.

The satirical elegiac fragment of Xenophanes that Nicolás mentions (21 B 7 DK, preserved through quotation in Diogenes Laërtios’s Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 8.1.36) is probably the oldest surviving mention of Pythagoras and most likely dates to shortly after Pythagoras’s death. The fragment makes fun of Pythagoras for believing in metempsychosis. Because of this fragment, the one fact about Pythagoras’s life that we can be the most certain of is that his contemporaries believed that he taught the doctrine of metempsychosis and that some regarded him as an eccentric because of this.

Thank you!

I had forgotten another doctrine of metempsychosis from the ancient Greek world: the one taught by Karpokrates. It’s described by Eirenaios (Irenaeus) in his work Against Heresies, 1.25, and later by Hyppolitos of Rome in Refutation of all Heresies, 7.32. In the latter work it can be read (paragraphs 7-8; I reproduce here the translation by John Henry MacMahon for the Ante-Nicene Fathers collection, which is in the public domain and available at Wikisource): “(The followers of Carpocrates) allege that the souls are transferred from body to body, so far as that they may fill up (the measure of) all their sins. When, however, not one (of these sins) is left, (the Carpocratians affirm that the soul) is then emancipated, and departs unto that God above of the world-making angels, and that in this way all souls will be saved. If, however, some (souls), during the presence of the soul in the body for one life, may by anticipation become involved in the full measure of transgressions, they, (according to these heretics,) no longer undergo metempsychosis. (Souls of this sort,) however, on paying off at once all trespasses, will, (the Carpocratians say,) be emancipated from dwelling any more in a body.”

And there is another very interesting belief in metempsychosis in the early Christian world. It is attributed by Eirenaios to Simon the Magician, the same person described in the Acts of Apostles (chapter 8) as confronting with the disciples. I quote Eirenaios’s text (Against Heresies, 1.23.2) according to the translation in Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. I (by Philip Schaff et al.):

“Now this Simon of Samaria, from whom all sorts of heresies derive their origin, formed his sect out of the following materials:—Having redeemed from slavery at Tyre, a city of Phœnicia, a certain woman named Helena, he was in the habit of carrying her about with him, declaring that this woman was the first conception of his mind, the mother of all, by whom, in the beginning, he conceived in his mind [the thought] of forming angels and archangels. For this Ennœa leaping forth from him, and comprehending the will of her father, descended to the lower regions [of space], and generated angels and powers, by whom also he declared this world was formed. But after she had produced them, she was detained by them through motives of jealousy, because they were unwilling to be looked upon as the progeny of any other being. As to himself, they had no knowledge of him whatever; but his Ennœa was detained by those powers and angels who had been produced by her. She suffered all kinds of contumely from them, so that she could not return upwards to her father, but was even shut up in a human body, and for ages passed in succession from one female body to another, as from vessel to vessel. She was, for example, in that Helen on whose account the Trojan war was undertaken; for whose sake also Stesichorus[283] was struck blind, because he had cursed her in his verses, but afterwards, repenting and writing what are called palinodes, in which he sang her praise, he was restored to sight. Thus she, passing from body to body, and suffering insults in every one of them, at last became a common prostitute; and she it was that was meant by the lost sheep.”

Later authors, such as Epiphanios (Panarion, her. 21) refer the same story.

In your description of the picture on the krater with Diomedes and Aineias fighting their positions seem to be switched (if I have not forgotten how to tell left from right). Judging by the greek captions Diomedes and Athena are on the left, and Aineias and Aphrodite are on the right. At the very least it does seem like the woman on the right is dragging the guy on her side away from the battle he’s losing.

I sincerely apologize! It seems that I must not have been paying attention and must have gotten my directions reversed for some reason. I have now corrected the caption. Thank you so much for pointing that out!