There is no period in all of human history that gets quite so much bad press as the Middle Ages. Popularly known as the “Dark Ages,” most people imagine that this was the worst possible time to be alive—a thousand years of poverty, backwardness, stagnation, superstition, and obscurantism.

It is popularly believed that, during this era, obscurantist Christians deliberately rounded up classical texts to destroy them, people burned witches, no one ever bathed, everyone thought the world was flat, people were constantly slaughtering and torturing each other for no reason, all people were fanatically orthodox Catholics, scientific and technological advancement was virtually nonexistent, doctors knew less about medicine than doctors in all other eras, and everyone was always miserable.

There is very little truth to any of these notions, however. The real Middle Ages are very different from the barbarous caricature that most people are familiar with. Although some historians do use the term “Dark Ages,” they use this term to refer to a specific period in medieval western European history lasting a little over three hundred years from the collapse of the western Roman Empire in the fifth century AD until the rise of the Carolinian Empire in the late eighth century AD.

In this article, I will debunk some of the most popular misconceptions about the Middle Ages. Then, at the end, I will explain why I, like many historians, believe that the term “Dark Ages” should be retired altogether.

The “Dark Ages” in the popular imagination

The phrase “Dark Ages” was first used to describe the Middle Ages by the Italian scholar Francesco Petrarch (lived 1304 – 1374 AD). In order to understand why Petrarch used this term, you need to understand something about how ancient and medieval people thought about their place in history, a subject I treat in depth in this article from April 2020.

Many ancient Greeks and Romans had a persistent notion that they were somehow deeply inferior to their ancestors. In the Iliad, the oldest surviving work of Greek literature, the poet emphasizes that the heroes he speaks of are so much better than people of his own time; they are stronger, faster, braver, more cunning, and generally better in every way.

During the time of the Roman Empire, people looked back on the mythical heroic age, but they also looked back on earlier historical times, seeing those times as better. The Greek writer Ploutarchos of Chaironeia (lived c. 46 – after c. 119 AD), for instance, laments in his essay Precepts of Statecraft that, in his own time, the opportunities for a bright young man to display his talents are severely limited compared to the opportunities that were available in the time of Greek city-states.

After the rise of Christianity and the collapse of the Roman Empire in the west, people continued to look back on earlier times as a sort of “Golden Age.” The poem “The Ruin,” written by an English monk in around the eighth century AD or thereabouts, describes a Roman ruin and imagines the builders of the ruin as members of a great lost civilization. The opening of the poem reads as follows, as translated by Aaron K. Hostetter:

“These wall-stones are wondrous —

calamities crumpled them, these city-sites crashed, the work of giants

corrupted. The roofs have rushed to earth, towers in ruins.

Ice at the joints has unroofed the barred-gates, sheared

the scarred storm-walls have disappeared—

the years have gnawed them from beneath. A grave-grip holds

the master-crafters, decrepit and departed, in the ground’s harsh

grasp, until one hundred generations of human-nations have

trod past. Subsequently this wall, lichen-grey and rust-stained,

often experiencing one kingdom after another,

standing still under storms, high and wide—

it failed…”

Petrarch totally bought into this narrative of classical antiquity as a “Golden Age” and everything after antiquity as a decline from that “Golden Age,” but he put his own spin on it.

ABOVE: Fresco of the Italian writer Francesco Petrarch, painted in around 1450 by the Florentine painter Andrea del Castagno

Petrarch believed that he was living in a time of great darkness, but that a momentous societal change was coming and that, in the coming era, people would devote themselves to the classics and the “Golden Age” of ancient Greece and Rome would return. He writes in his poem Africa, book nine, lines 451-457, as translated by Theodore E. Mommsen:

“My fate is to live among varied and confusing storms. But for you perhaps, if as I hope and wish you will live long after me, there will follow a better age. This sleep of forgetfulness will not last for ever. When the darkness has been dispersed, our descendants can come again in the former pure radiance.”

Later historians took up Petrarch’s portrayal of the Middle Ages as a time of “darkness.” Protestant polemicists explicitly linked the supposed “darkness” of the Middle Ages with Roman Catholicism. For instance, the anti-Catholic book Popery, an Enemy to Civil and Religious Liberty; and Dangerous to Our Republic by W. C. Brownlee, published in New York in 1836, warns:

“Do Protestants not know that these ‘Dark Ages,’ of which we speak with sorrow, were, in fact, the Augustine Age of Popery? Then it flourished in the beauty and supremacy of its glory! No true Roman Catholic, except when among his heretical neighbours, ever thinks of speaking disrespectfully of those ‘Dark Ages.’ And every priest of Rome, true to the pious maxim, that ignorance is the mother of devotion, is at all times prepared to laud, in no measured terms, the glory of the reign of Catholicism in the Dark Ages!”

This portrayal of the Middle Ages as a dark time when the world was enslaved by Catholicism still shapes the way we think about the period today.

Even today, the Middle Ages are still widely politicized. In the same way that Protestant polemicists in the nineteenth century warned that the spread of “Popery” in the United States would destroy civil and religious liberties and take society back to the “Dark Ages,” it has become common for people today to warn that anything in society that they happen to dislike is threatening to do this very thing.

For instance, a headline for an article published in October 2018 on the left-wing media site Truthdig warns that a Supreme Court with Brett Kavanaugh on it will “take us back to the Dark Ages.” A headline for an article published by the BBC in November 2018 proclaims that antibiotic resistant bacteria “could take us back to the ‘dark ages.'” An article published in The Daily Mail in November 2019 even sensationally claims “The internet will send us back to the Dark Ages.”

The dominant worldview of the contemporary age is more-or-less the exact opposite of the worldview that most ancient and medieval people subscribed to. Instead of seeing the past as a “Golden Age” and the present as a time of decline, most people today see the past as a “Dark Age” and the present as a time of progress.

ABOVE: Illustration by Lucas Cranach the Elder from Martin Luther’s 1521 pamphlet Passionary of the Christ and Antichrist portraying the Pope as the Antichrist. The modern perception of the Middle Ages has been primarily shaped by Protestant propaganda.

Will the real Dark Ages please stand up?

The so-called “Dark Ages” have become so mythologized that it is often hard to tell which historical era people are actually talking about when they use this term. The term is often used by members of the general public to describe the entire Middle Ages, from the collapse of the western portion of the Roman Empire in the fifth century AD until the beginning of the Italian Renaissance in around the mid-fifteenth century AD.

At the same time, the term “Dark Ages” is sometimes used by historians to refer more specifically to the Early Middle Ages (lasted c. 475 – c. 800 AD), the period from the collapse of the western Roman Empire until the rise of the Carolingian Empire in the late eighth century AD.

This confusion about what the term “Dark Ages” refers to makes it especially difficult to write about them. Therefore, I will first address misconceptions pertaining to the Middle Ages in general. Then, at the end of the article, I will address the question of whether it is appropriate for us refer to the Early Middle Ages as the “Dark Ages.”

ABOVE: Map from Wikimedia Commons showing the Carolingian Empire at its greatest extent at the time of the death of Charlemagne in 814 AD. The Carolingian Empire was the first major empire to arise in Europe after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West.

Misconception #1: During the Middle Ages, there was a systematic campaign by Christians to destroy classical texts.

Probably the most widespread misconception about the Middle Ages is the notion that Christian authorities intentionally rounded up classical texts and burned them because they had been written by pagans. This misconception is so pervasive that even some debunkers of misconceptions about the Middle Ages have fallen for it. For instance, Richard Shenkman writes on page 40 of his book Legends, Lies & Cherished Truths of World History, which was originally published in 1993 by HarperCollins Publishers:

“That Catholic monks helped keep classical knowledge alive in the Middle Ages by assiduously copying the ancient texts is flatly untrue. In fact, the church engaged in a systematic campaign to suppress the classics, being that the classics had been produced by pagans.”

I’m usually a fan of Shenkman, but, in this particular instance, he is completely wrong; the “misconception” that he is “debunking” here is, in fact, the truth and what he claims is the truth is, in fact, the misconception.

Now, to give Shenkman credit, there is a very slight grain of truth to this misconception in that some Christian authorities in late antiquity and the Middle Ages did try to destroy a few very specific kinds of ancient texts. As we shall see in a moment, however, there was not in any way a general “systematic campaign to suppress the classics.”

The first kind of ancient text that some Christians did try to destroy were ancient Greco-Roman occult writings. The Book of the Acts of the Apostles 19:17–20, for instance, famously claims that, while Paul was preaching in the Greek city of Ephesos in Asia Minor, people who had converted to Christianity gathered up any writings they had about magic and publicly burned them. Here is what the actual passage says, as translated in the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV):

“When this became known to all residents of Ephesus, both Jews and Greeks, everyone was awestruck; and the name of the Lord Jesus was praised. Also many of those who became believers confessed and disclosed their practices. A number of those who practiced magic collected their books and burned them publicly; when the value of these books was calculated, it was found to come to fifty thousand silver coins. So the word of the Lord grew mightily and prevailed.”

The writings that this passage refers to, however, are silly and superstitious works that I don’t think any rationalist should particularly care about. For instance, here is a spell from the Kyranides, an ancient Greek collection of magical texts compiled in around the fourth century AD, as translated by J. C. McKeown in his book A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities:

“The testicles of a weasel can both ensure and prevent conception. If the right testicle, reduced to ashes and mixed in a paste with myrrh, is inserted into a woman’s vagina on a small ball of wool before intercourse, she will conceive immediately. But if the left testicle is wrapped in mule-skin and attached [we are not told how] to the woman, it prevents conception. The following words have to be written on the mule-skin: ‘ioa, oia, rauio, ou, oicoochx.’ If you are skeptical, try it on a bird that is laying eggs; it will not lay any eggs at all while the testicle is attached to it” (Kyranides 2.7).

Here’s another example from the Kyranides, also translated by McKeown:

“If you take some hairs from a donkey’s rump, burn them and grind them up, and then give them to a woman in a drink, she will not stop farting” (Kyranides 2.31).

I don’t think anyone should greatly mourn the loss of these sorts of texts. They certainly have some historical value, but I don’t think they have any serious literary or scientific value.

Furthermore, it is hard to emphasize just what miserable failures Christian authorities were at suppressing occult texts. Literally countless reams worth of Greco-Roman spells and occult writings have survived to the present day. You could probably fill a whole library with nothing but ancient Greek and Roman magical texts alone.

ABOVE: The Preaching of Saint Paul at Ephesus, painted in 1649 by Eustache Le Sueur

In addition to occult writings, some Christian authorities were also interested in destroying Christian writings that they regarded as heretical. Once again, however, they were phenomenally bad at this, as evidenced by the massive number of surviving Christian apocryphal texts, such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, the Gospel of Judas, the Apocalypse of Peter, the Pistis Sophia, and literally too many others to count. No matter how strongly Christian authorities condemned these writings, people just wouldn’t stop reading them.

The final kind of ancient text that Christians were interested in suppressing were anti-Christian polemics written by pagan authors such as the Neoplatonic philosopher Iamblichos (lived c. 245 – c. 325 AD) and the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate (lived c. 332 – 363 AD). None of these polemics have survived to the present day complete, but we have a very good impression of the kinds of arguments and accusations they made because, ironically, their arguments have been preserved through works written by Christian apologists in response to them.

To give an extreme example, in around 170 AD or thereabouts, a Greek controversialist named Kelsos wrote an anti-Christian polemic titled The True Word. In around 248 AD, the Christian scholar Origenes of Alexandria (lived c. 184 – c. 253 AD) wrote a response to it titled Against Kelsos, in which he quotes profusely from Kelsos’s original treatise, responding to each and every argument Kelsos made. Although Kelsos’s original treatise has been lost, we basically know everything it said thanks to Origenes.

ABOVE: First page of a Greek manuscript of Origenes of Alexandria’s apologetic treatise Against Kelsos

Late antique and medieval Christians seem to have had virtually no interest in destroying ancient Greek and Roman scientific, literary, or philosophical texts. On the contrary, in general, ancient and medieval Christians were actually great admirers of classical Greek and Roman literature and philosophy. Virtually all works of ancient Greek and Roman literature that have survived to the present day have survived because they were copied by Christians.

The early Christian apologist and Church Father Ioustinos Martys (lived c. 100 – c. 165 AD) argued that “τὰ σπέρματα τοῦ λόγου” (tà spérmata toû lógou), or “the seeds of the Word,” had been planted long before the coming of Christ and that Greek philosophers such as Socrates and Plato had, in fact, been unknowing Christians and that their writings were divinely inspired.

The Church Father Klemes of Alexandria (lived c. 150 – c. 215 AD), who was a Greek-speaking Egyptian convert to Christianity, was such an ardent fan of Greek philosophy that he regarded it as nothing short of a secondary revelation. In his treatise Stromateis 1.5, Klemes gives a famous description of what Christianity is like. He writes, as translated by William Wilson, “The way of truth is therefore one. But into it, as into a perennial river, streams flow from all sides.” The “streams” in this simile represent many different ideas from many different cultures. Certainly, Klemes saw Greek philosophy as one of those streams.

The theologian and apologist Origenes of Alexandria, whom I mentioned earlier in this article, was, like Klemes, deeply learned about Greek philosophy and literature and he taught ideas from all different schools of Greek philosophy to his students. Origenes’s student Gregorios Thaumatourgos writes in his Panegyric 13, as translated by David T. Runia:

“Origen considered it right for us to study philosophy in such a way that we read with utmost diligence all that has been written, both by the philosophers and the poets of old, rejecting nothing and repudiating nothing, except only what had been written by the atheists . . . who deny the existence of God or providence.”

There were a few early Christians who rejected Greek learning. Klemes and Origenes’s contemporary, the Christian apologist Tertullian (lived c. 155 – c. 240 AD), who lived in North Africa and wrote in the Latin language, was one such individual. Tertullian famously deplored Greek philosophy as a source of heresy in chapter seven of his apologetic treatise De Praescriptione Haereticorum (“On the Proscription of Heretics”), writing, as translated by Peter Holmes:

“Whence spring those ‘fables and endless genealogies,’ and ‘unprofitable questions,’ and ‘words which spread like a cancer?’ From all these, when the apostle would restrain us, he expressly names philosophy as that which he would have us be on our guard against. Writing to the Colossians, he says, ‘See that no one beguile you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, and contrary to the wisdom of the Holy Ghost.’ He had been at Athens, and had in his interviews (with its philosophers) become acquainted with that human wisdom which pretends to know the truth, whilst it only corrupts it, and is itself divided into its own manifold heresies, by the variety of its mutually repugnant sects.”

“What indeed has Athens to do with Jerusalem? What concord is there between the Academy and the Church? what between heretics and Christians? Our instruction comes from ‘the porch of Solomon,’ who had himself taught that ‘the Lord should be sought in simplicity of heart.’ Away with all attempts to produce a mottled Christianity of Stoic, Platonic, and dialectic composition! We want no curious disputation after possessing Christ Jesus, no inquisition after enjoying the gospel! With our faith, we desire no further belief.”

Tertullian, however, was a member of the Montanist sect, which was seen by other Christians at the time as heretical and extremist. It wouldn’t be entirely inaccurate to call him a “fundamentalist.” Furthermore, there is a degree of hypocrisy in Tertullian’s rejection of the classics, since he himself was highly trained in classical rhetoric and made extensive use of this training. Indeed, De Praescriptione Haereticorum itself is full of classical rhetorical appeals and arguments.

The general feeling among mainstream Christians in late antiquity and the Middle Ages was that it was good to study classical literature and philosophy, but that readers of such works needed to be careful to not let their study of pagan texts distract them from studying the Bible.

Jerome (lived c. 347 – 420 AD), the Dalmatian-born translator of the Latin Vulgate, was such an avid reader of Cicero that he tells us he feared that, on Judgement Day, God might turn him away, saying that he was a follower of Cicero, not a follower of Christ. Jerome gave up reading the classics for a period of his life, devoting himself to the study of the Bible instead, but he couldn’t stay away from the classics forever; later in life, he returned to studying them.

ABOVE: Jerome in his Study, painted in 1480 by the Italian Renaissance scholar Domenico Ghirlandaio

The reason why so many ancient texts have been lost is not because medieval Christians relentlessly hunted them down to destroy them, but rather because the texts that have been lost were simply not copied enough. In ancient and medieval times, the printing press did not exist and the only way to copy a text was by hand. Naturally, this was a very time-consuming, labor-intensive, and often expensive task.

In ancient times, people in the Mediterranean world mostly wrote on papyrus, which usually has about the same life expectancy as modern acid paper. Under normal conditions of wear and use, a papyrus manuscript might be expected to last about fifty years. In the Middle Ages, people mostly wrote on parchment, which is much more durable. Texts still had to be copied by hand, though.

It is often specifically claimed that medieval Christians intentionally burned all the works of the Greek poet Sappho (lived c. 630 – c. 570 BC). As I discuss in this article from December 2019, however, this is nothing but an urban legend that originated among western European Renaissance scholars in the sixteenth century. All of these scholars were writing many centuries after the events they describe supposedly took place and none of them cite any sources for their claims.

Furthermore, the Renaissance scholars couldn’t even agree on who it was that supposedly burned Sappho’s poems in the first place. The Italian scholar Pietro Alcionio (lived c. 1487 – 1527) thought it was a Byzantine emperor (whose name he apparently couldn’t remember). The later Italian scholar Gerolamo Cardano (lived 1501 – 1576) thought it was the eastern Church Father Gregorios Nazianzenos (lived c. 329 – 390 AD). The French scholar Joseph Justus Scaliger (lived 1540 – 1609) thought it was Pope Gregory VII (lived 1015 – 1085).

Not only is the evidence to support the claim that Christians intentionally destroyed Sappho’s poems extremely weak, it makes very little sense why Christians would target Sappho of all writers. Judging from the works that have survived, Sappho’s poems are mostly about everyday life, motherhood, old age, partings, and love. Probably the most obscene surviving passage from Sappho comes from fragment 94, which is known to us from a scrap of parchment dated to the sixth century AD. It reads as follows, as translated by M. L. West:

“You remember how we looked after you;

or if not, then let me remind

[…]

all the lovely and beautiful times we had,

all the garlands of violets

and of roses and

and … that you’ve put on in my company,

all the delicate chains of flowers

that encircled your tender neck

[…]

[…]

and the costly unguent with which

you anointed yourself, and the royal myrrh.

On soft couches …

tender …

you assuaged your longing …”

So, yeah, not very explicit at all.

On the other hand, medieval Christians kindly preserved for us all sorts of classical texts that are millions of times more obscene than anything Sappho ever wrote, such as eleven complete comedies of Aristophanes full of jokes about sex and feces, nine volumes of Martial’s Epigrams, and the Priapeia—a collection of eighty gratuitously obscene Latin poems about the fertility god Priapos, who is noted for his gigantic, perpetually erect penis.

To give you an idea what I’m talking about, here’s Martial’s Epigrams 7.67.1:

“Pudicat pueros tribas Philaenis

et tentigine saevior mariti

undenas dolat in die puellas.”

Here is a translation of the poem by Harriette Andreadis:

“That tribade Philaenis sodomizes boys,

and with more rage than a husband in his stiffened lust,

she works eleven girls roughly every day.”

Again, medieval Christians kindly preserved nine whole volumes of these epigrams, most them just as obscene as this one or even more so. It’s hard to imagine that they would tolerate this sort of filth, but, for some reason, find Sappho’s poems objectionable.

It is far more likely that the real reason why so few of Sappho’s poems have survived is not because there was a systematic campaign to destroy them, but rather because people were just less interested in reading her poems, so they didn’t get copied as much. Sappho wrote in the Aeolic dialect, which late antique audiences found notoriously archaic and difficult to understand. Furthermore, from late antiquity onwards, audiences were generally less interested in lyric poetry and more interested in rhetoric.

The idea that there was some kind of systematic campaign to eliminate Sappho’s poems is also seriously undermined by the fact that we have vastly more surviving poems by Sappho than we do for the vast majority of other early Greek lyric poets. With Sappho, we have around a dozen nearly complete poems; whereas, for most other early Greek lyric poets, all we have is a name and maybe a couple lines at the most.

ABOVE: Detail of Sappho from Raphael’s fresco Parnassus, which decorates one of the Raphael Rooms of the Apostolic Palace in Vatican City

Another popular claim holds that medieval Christians intentionally suppressed the writings of the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse (lived c. 287 – c. 212 BC) because they hated science. This claim is based on an extremely distorted and incomplete presentation of evidence that has been promoted by a variety of anti-religious writers. I’ve already written an article refuting this claim in-depth, but I will briefly summarize what really happened here.

In around the middle of the tenth century AD, a Byzantine scribe in Constantinople produced a parchment codex containing seven treatises by Archimedes. This codex is referred to by modern scholars as “Archimedes Codex C.” It contains the full Greek text of Archimedes’s treatise The Method of Mechanical Theorems, which is not known from any other manuscripts, as well as the Greek texts of the treatises Stomachion and On Floating Bodies. Arabic translations of these treatises are known from other manuscripts, but Archimedes Codex C is the only surviving manuscript containing the full Greek texts of these treatises.

In 1204 AD, the city of Constantinople was sacked by the knights of the Fourth Crusade. Somehow, Archimedes Codex C wound up in the possession of a Christian priest named Ioannes Myronas, who was living in Jerusalem. In 1229 AD, under Myronas’s ownership, the codex was unbound, the writing incompletely scraped off, and the parchment was reused to make a Christian prayer book, known as the Archimedes Palimpsest.

In the early twentieth century, the Danish scholar Johan Ludvig Heiberg (lived 1854 – 1928) transcribed the incompletely erased text of the treatises by Archimedes with the aid of a magnifying glass and a camera. He published the complete Greek text of Archimedes’s Method of Mechanical Theorems in 1907.

During the Greco-Turkish War (lasted 1919 – 1922), the Archimedes Palimpsest was stolen from the library where it was held in İstanbul. It was shuffled around on the illegal antiquities market, stored in a damp cellar for years, horribly mistreated, and eventually sold at Christie’s Auction House in 1998 for two million dollars to an anonymous American billionaire.

ABOVE: Painting from 1620 by the Italian painter Domenico Fetti showing how he imagined Archimedes might have looked (No one knows how he really looked.)

Various anti-religious writers have tried to cite the Archimedes Palimpsest as evidence that medieval Christians hated science. There are a lot of facts they leave out that seriously undermine their argument, however:

- Archimedes Codex C was originally copied by a Christian Byzantine scribe. The fact that the codex was copied at all is proof that at least some medieval Christians cared about mathematics and science.

- The decision to erase the text from Archimedes Codex C and reuse the parchment to make a palimpsest was made by one individual owner of the codex; it does not in any way indicate that all medieval Christians were militant obscurantists hellbent on destroying classical texts.

- We don’t know why Ioannes Myronas chose to reuse the parchment from Archimedes Codex C to make a prayer book. For all we know, he already had other copies of the treatises contained in it and those copies just haven’t survived. He almost certainly didn’t think he was destroying the last surviving copies of any of those treatises.

- It was extremely common for people in antiquity and the Middle Ages to reuse parchment from old manuscripts that they weren’t using to make palimpsests. The Greeks and Romans themselves did it all the time; it was by no means just a Christian thing. It was basically the ancient and medieval equivalent of recycling. The alternative was to simply throw out the old manuscript. If Ioannes Myronas had thrown out Archimedes Codex C, we probably wouldn’t have the unique texts that it contains. Because he chose to recycle, though, we have several texts that would otherwise have been lost.

Clearly, the Archimedes Palimpsest is not evidence that there was any kind of systematic effort by Christians to destroy classical texts.

ABOVE: Photograph of a page from the Archimedes Palimpsest, showing Archimedes’s text written underneath the text of the prayer book

Misconception #2: During the Middle Ages, there were widespread, church-sanctioned witch hunts.

It is widely believed that people during the Middle Ages went around burning witches. In reality, there were no widespread church-sanctioned witch hunts, witch trials, or witch burnings at all during the Middle Ages. In fact, the official position of the Roman Catholic Church throughout almost the entire Middle Ages was that witches did not exist and that anyone who believed in the existence of witches was a heretic.

The Canon Episcopi, a passage that is first attested in the early tenth century AD and that became part of the official canon law of the Catholic Church in the eleventh century AD, unambiguously states that anyone who believes in witchcraft is a heretic. The passages reads as follows, as translated by Henry C. Lea in his book Materials Toward a History of Witchcraft:

“Bishops and their officials must labor with all their strength to uproot thoroughly from their parishes the pernicious art of sorcery and malefice invented by the devil, and if they find a man or woman follower of this wickedness to eject them foully disgraced from the parishes. For the Apostle says, ‘A man that is a heretic after the first and second admonition avoid.’ Those are held captive by the Devil who, leaving their creator, seek the aid of the Devil. And so Holy Church must be cleansed of this pest.”

“It is also not to be omitted that some unconstrained women, perverted by Satan, seduced by illusions and phantasms of demons, believe and openly profess that, in the dead of night, they ride upon certain beasts with the pagan goddess Diana, with a countless horde of women, and in the silence of the dead of the night to fly over vast tracts of country, and to obey her commands as their mistress, and to be summoned to her service on other nights.”

“But it were well if they alone perished in their infidelity and did not draw so many others into the pit of their faithlessness. For an innumberable multitude, deceived by this false opinion, believe this to be true and, so believing, wander from the right faith and relapse into pagan errors when they think that there is any divinity or power except the one God.”

“Wherefore the priests throughout their churches should preach with all insistence to the people that they may know this to be in every way false, and that such phantasms are sent by the devil who deludes them in dreams. Thus Satan himself, who transforms himself into an angel of light, when he has captured the mind of a miserable woman and has subjected her to himself by infidelity and incredulity, immediately changes himself into the likeness of different personages and deluding the mind which he holds captive and exhibiting things, both joyful and sorrowful, and persons, both known and unknown, and leads her faithless mind through devious ways.”

“And while the spirit alone endures this, she thinks these things happen not in the spirit but in the body. Who is there that is not led out of himself in dreams and nocturnal visions, and sees much sleeping that he had never seen waking? Who is so stupid and foolish as to think that all these things that are done in the spirit are done in the body, when the Prophet Ezekiel saw visions of God in spirit and not in body, and the Apostle John saw and heard the mysteries of the Apocalypse in spirit and not in body, as he himself says ‘I was rapt in Spirit’. And Paul does not dare to say that he was rapt in his body.”

“It is therefore to be publically proclaimed to all that whoever believes in such things, or similar things, loses the Faith, and he who has not the right faith of God is not of God, but of him in whom he believes, that is the devil. For of our Lord it is written, ‘All things were made by Him.’ Whoever therefore believes that anything can be made, or that any creature can be changed to better or worse, or transformed into another species or likeness, except by God Himself who made everything and through whom all things were made, is beyond a doubt an infidel.”

The dogma that witches did not exist slowly began to change, starting in around the fourteenth century, as the church began to gradually endorse popular beliefs in witchcraft. Witch trials first became common and widespread in western Europe in the sixteenth century in the wake of the Protestant Reformation.

ABOVE: Imaginative nineteenth-century woodcut depicting what the artist imagined a witch burning might have looked like

Ironically, the height of the witch trials was actually in the late 1500s and early 1600s, which just so happens to be the same time period as the so-called “Scientific Revolution.” Believe it or not, revered luminaries such as William Harvey, William Shakespeare, Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, Galileo Galilei, René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, John Locke, Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, Isaac Newton, and Montesquieu all lived during the height of the witchcraft hysteria in western Europe.

The only reason why people imagine that witch hunts must have happened during the Middle Ages is because people associate the late 1500s and early 1600s with forward thought, enlightenment, and rationality; whereas, for most people, witch trials seem like the very embodiment of everything backwards, irrational, and barbarous, so people naturally assume that the witch trials must have happened during an earlier, “less civilized” time period.

ABOVE: Portrait from 1648 of the great scientist, philosopher, and mathematician René Descartes, whose life just so happens to correspond almost exactly with the height of the witch trials in western Europe

Misconception #3: During the Middle Ages, no one ever bathed and they went around covered in their own filth.

Many people today also have the impression that people in western Europe during the Middle Ages never bathed, that they were always absolutely covered in filth, and that they all stank like pigs.

This misconception has been heavily reinforced by popular culture. In films and television shows, medieval peasants are always depicted as dirty and disgusting. For instance, the 1975 British comedy film Monty Python and the Holy Grail shows all the peasants completely covered in filth, as though they had all been rolling in the mud and intentionally smearing the dirt all over their faces.

ABOVE: Shot from the 1975 British comedy film Monty Python and the Holy Grail showing peasants literally covered in filth

This idea is inaccurate, however. While it is true that personal hygiene during the Middle Ages was not nearly as good as it is today, it did exist—even among peasants. Health manuals from throughout the Middle Ages recommend washing any visible dirt from one’s body regularly and correctly describe allowing the buildup of visible dirt as unhealthy.

Bathing is frequently mentioned in medieval texts and there are many surviving medieval depictions of people bathing, indicating that it was a relatively common activity. During the Early Middle Ages, Pope Gregory I (lived c. 540 – 604 AD) recommended that people should bathe on a regular basis, although he warned against the potential for excessive bathing to become a sinful luxury.

For the rich and powerful, bathing was a popular leisure activity. The Frankish scholar Einhard (lived c. 775 – 840 AD) writes that the emperor Charlemagne loved bathing so much that he made it into a social activity. According to Einhard, Charlemagne would invite not only his sons to bathe with him on regular occasions, but also various friends, noblemen, attendants, and bodyguards.

It is true that at least some people during the Middle Ages did think that there could be such a thing as too much bathing. For instance, the Benedictine monk Petrus Damianus (lived c. 1007 – c. 1072) ridiculed the Byzantine princess Theophano (lived c. 955 – 990), the empress consort of Emperor Otto II of the Holy Roman Empire, for the fact that she bathed multiple times every day.

According to Petrus Damianus, Theophano’s excessive bathing was a sign of decadence. Bathing multiple times a day, however, would be considered unusual even today in the twenty-first century and Petrus Damianus is far from representative of what the majority of people of his era thought, since he was unusually puritanical.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of an ivory book cover dated to c. 982 AD depicting Jesus Christ crowning Otto II and his wife Theophano, the Byzantine princess whom Petrus Damianus criticized for excessive bathing

While it is true that most commoners in western Europe during the Middle Ages could not afford private baths, most of them still bathed on a relatively regular basis. Public baths, a holdover from Roman times, were very common and very popular throughout the Middle Ages.

In the city of Paris during the thirteenth century, there were at least thirty-two public baths throughout the city. Bathhouses were so plentiful in Paris during the twelfth century that the English writer Alexander Neckham (lived 1157 – 1217), who lived in Paris, wrote that he was often woken up by the sound of people shouting in the streets that the baths were hot.

Public bathhouses during the Middle Ages were often located next to bakeries so that the baker’s ovens could be used to heat the water. Many people would buy bread and other foods and eat them while they bathed. The historian Virginia Smith states on page 179 of her book Clean: A History of Personal Hygiene and Purity, which published in 2007 by the Oxford University Press:

“By the fifteenth-century, bath feasting in many town bathhouses seems to have been as common as going out to a restaurant was to become four centuries later.”

Public bathhouses were also often associated with prostitution, however, and many public bathhouses also functioned as brothels, which led some people to be wary of them.

ABOVE: Woodcut by the German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer (lived 1471 – 1528) depicting a men’s bathhouse

Therefore, contrary to how they are often portrayed in modern popular culture, very few people during the Middle Ages would have been walking around visibly caked in filth and grime. Ironically, personal hygiene in western Europe during the Middle Ages was probably better than personal hygiene in most western cultures throughout most of the Early Modern Period (lasted c. 1450 – c. 1750).

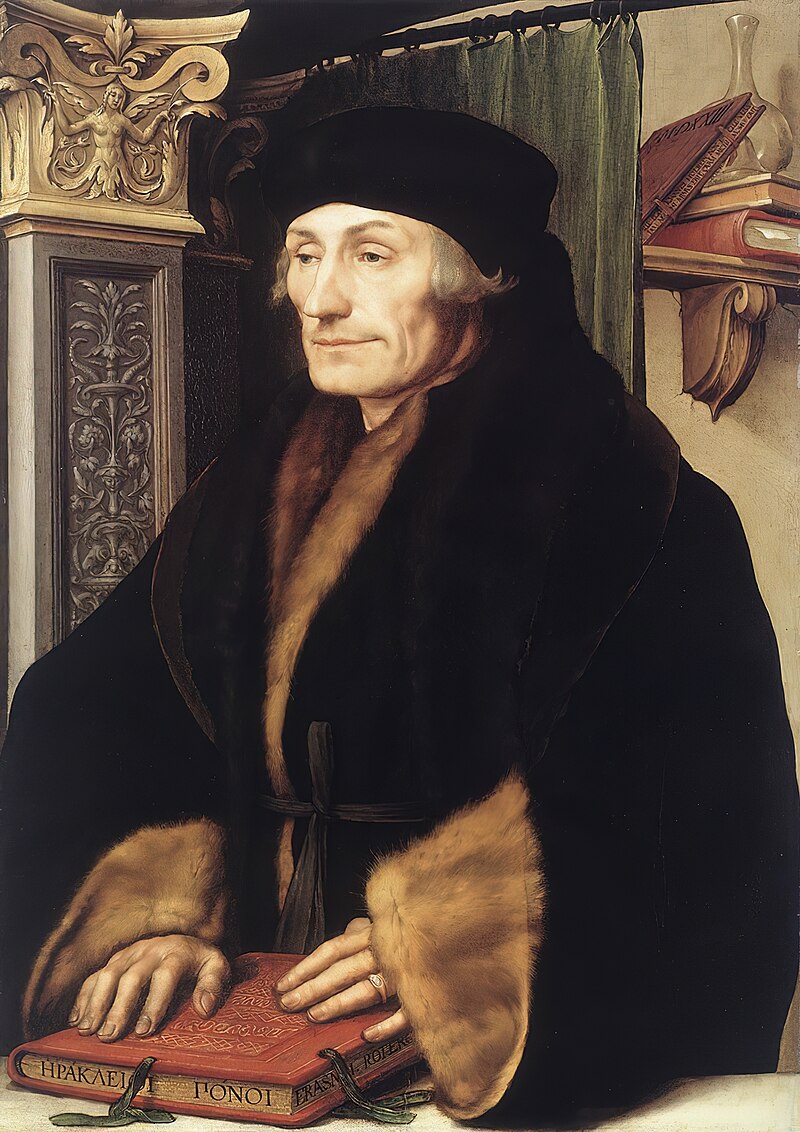

Bathhouses fell rapidly out of favor in western Europe during the early sixteenth century. In 1526, the Dutch humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus (lived 1466 – 1536) attributed the sudden decline in the popularity of the bathhouses during his lifetime to the widespread epidemic of syphilis that struck in the 1490s and grew throughout the early sixteenth century. Erasmus writes:

“Twenty-five years ago, nothing was more fashionable in Brabant than the public baths. Today there are none, the new plague [i.e. syphilis] has taught us to avoid them.”

Erasmus’s association of the bathhouses with syphilis is not nearly as absurd as it sounds. People who frequented brothels were more likely to contract syphilis, since it is a sexually transmitted disease, and, since bathhouses in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries often also functioned as brothels, this may have led people to fear the bathhouses, knowing that people who frequented them tended to be more likely to contract syphilis.

ABOVE: Portrait of the Dutch humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus, who observed the sudden decline in popularity of bathhouses during his lifetime and associated it with fear of syphilis

Misconception #4: During the Middle Ages, educated people believed that the earth was flat.

Unfortunately, it is still widely believed that people during the Middle Ages thought the earth was flat. Even some very intelligent and highly educated people still believe this. For instance, in January 2016, the renowned astrophysicist and science communicator Neil deGrasse Tyson got into a Twitter argument with a rapper by the pseudonym B.o.B., who thinks the earth is flat.

In the course of the argument, Tyson called B.o.B. “five centuries regressed in [his] thinking.” When someone pointed out to him that knowledge of the sphericity of the earth goes way back before five hundred years ago, Tyson replied that the knowledge that the earth is spherical was “lost to the Dark Ages.”

Neil deGrasse Tyson is a very intelligent man and he undoubtedly knows far more about astrophysics than I ever will, but, on this particular historical issue, he is dead wrong. The sphericity of the earth was indeed discovered by the ancient Greeks, but this knowledge was never lost; in fact, as I discuss in this article I published in February 2019, the sphericity of the earth was almost universally accepted as fact by educated people in western Europe throughout the Middle Ages.

It is unclear exactly when the ancient Greeks first figured out that the earth is a sphere, but the Greek philosopher Plato (lived c. 428 – c. 347 BC) explicitly describes it as spherical in his Phaidon 108d-109a. In that dialogue, one of the speakers says this, as translated by Harold North Fowler:

“…the earth is round and in the middle of the heavens, it needs neither the air nor any other similar force to keep it from falling, but its own equipoise and the homogeneous nature of the heavens on all sides suffice to hold it in place; for a body which is in equipoise and is placed in the center of something which is homogeneous cannot change its inclination in any direction, but will remain always in the same position. This, then, is the first thing of which I am convinced.”

Plato’s student Aristotle (lived 384 – 322 BC) gives several detailed arguments in favor of the sphericity of the earth in his On the Heavens 296b-297b, using empirical evidence.

Nearly all authors writing after the time of Aristotle describe the earth as a sphere. There were a few people who disagreed with Plato and Aristotle, such as the philosopher Epikouros of Samos (lived 341 – 270 BC), who made a point to disagree with Plato about everything he possibly could, but, overall, the consensus in favor of sphericity remained remarkably stable.

The consensus did face slight disruption after the rise of Christianity. The Christian apologist Lactantius (lived c. 250 – c. 325 AD) notably mocked the idea of a spherical earth. A few centuries later, in the east, the die-hard Biblical literalist Kosmas Indikopleustes (lived c. 500 – after c. 550 AD) wrote a book titled Christian Topography in which he advanced the bizarre claim that the universe is shaped like the Ark of the Covenant—a box with a floor, walls, and a lid on top.

People like Kosmas, however, were fringe theorists whose ideas about cosmology were generally not taken seriously, even by Christian scholars. The Northumbrian monk Bede the Venerable (lived c. 672 – 735 AD) clearly outlines the mainstream position of medieval scholars in his treatise On the Reckoning of Time, which is that the earth is roughly a sphere. Bede writes in chapter 46, as translated by William D. McCready:

“We refer to the sphere of the earth, not that it is perfectly spherical in shape, given the great difference of mountains and plains, but that it would constitute a perfectly formed sphere if all of the lines were enclosed in the circumference of its circuit. Hence it is that the stars of the northern region are always visible to us, while southern ones never are. Conversely, these northern stars are never seen in southern regions, owing to the obstruction of the globe of the earth. The country of the Troglodytes, and Egypt, which is adjacent to it, do not see the Great and Little Bear, and Italy does not see Canopus.”

The scholar Johannes de Sacrobosco (lived c. 1195 – c. 1256 AD) is known for writing an introductory astronomy textbook titled Tractatus de Sphaera, which has survived. In the first chapter, Johannes explains how we know the earth is a sphere. Here is his explanation, as translated by Lynn Thorndike:

“That the earth, too, is round is shown thus. The signs and stars do not rise and set the same for all men everywhere but rise and set sooner for those in the east than for those in the west; and of this there is no other cause than the bulge of the earth. Moreover, celestial phenomena evidence that they rise sooner for Orientals than for westerners. For one and the same eclipse of the moon which appears to us in the first hour of the night appears to Orientals about the third hour of the night, which proves that they had night and sunset before we did, of which setting the bulge of the earth is the cause.”

“That the earth also has a bulge from north to south and vice versa is shown thus: To those living toward the north, certain stars are always visible, namely, those near the North Pole, while others which are near the South Pole are always concealed from them. If, then, anyone should proceed from the north southward, he might go so far that the stars which formerly were always visible to him now would tend toward their setting. And the farther south he went, the more they would be moved toward their setting.”

“Again, that same man now could see stars which formerly had always been hidden from him. And the reverse would happen to anyone going from the south northward. The cause of this is simply the bulge of the earth. Again, if the earth were flat from east to west, the stars would rise as soon for westerners as for Orientals. which is false. Also, if the earth were flat from north to south and vice versa, the stars which were always visible to anyone would continue to be so wherever he went, which is false. But it seems flat to human sight because it is so extensive.”

Medieval depictions of the earth consistently show it as a sphere. For instance, below is a twelfth-century manuscript illustration from the Liber Divinorum Operum by Hildegard of Bingen. Notice that the people and trees are shown sticking out from the earth radially:

Here is a fourteenth-century illustration from a manuscript copy of L’Image du Monde, originally written by the French priest and poet Gautier de Metz in around 1246:

The fact that the sphericity of the earth was common knowledge is also evidenced by the fact that it was incorporated into popular symbolism. One of the primary symbols of kingship during the Middle Ages was the globus cruciger, a sphere with a cross on top of it. The sphere was supposed to represent the earth and the cross was supposed to represent Christ’s dominion over it. Clearly it must have been common knowledge that the earth was spherical, or else the globus cruciger would not have been a meaningful symbol.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of a globus cruciger

Anyone who lived in western Europe during the Middle Ages and had even the vaguest smattering of an education knew full well that the earth is a sphere. Sure, there were a handful of cranks like Kosmas Indikopleustes who thought that the earth was some other shape, but there are plenty of cranks today who have similar ideas.

The idea that people in western Europe during the Middle Ages thought the earth was flat is a canard that originated in the late seventeenth century and was popularized by the book A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, which was written by the American writer Washington Irving (lived 1783 – 1859). The book was first published in January 1828 and, although it purported to be a work of “history,” it was, in fact, almost entirely a work of fiction.

Naturally, as books of that nature usually tend to do, it became a wild success and sold no less than 175 editions in both North America and Europe, spreading a great deal of misinformation along the way. Because the book was seen as factual, children in schools were commonly assigned to read it. These children grew up believing that, before Columbus, everyone had thought the world was flat. Thus, one man’s lie deceived almost the whole world.

ABOVE: Daguerreotype photograph of the American writer Washington Irving, the man most directly responsible for the promotion of the misconception that people in the Middle Ages believed the world was flat, from between 1855 and 1860

Misconception #5: The Middle Ages were an effectively lawless time of extraordinary violence and cruelty, when people were constantly murdering, raping, and torturing each other.

It is absolutely true that a lot of violent and terrible things happened during the Middle Ages. Unfortunately, as I discuss in this article from December 2019, modern fantasy films and television shows have given many people a wildly inflated impression of just how violent the medieval world really was. The level of violence associated with the Middle Ages in modern fantasy is often so over-the-top that you don’t have to know much about the Middle Ages at all to spot how ridiculous it is.

To give a particularly extreme example, the opening scene of the very first episode of the fantasy drama series American Gods portrays a group of Vikings who have come to North America. They discover that the natives are hostile and they decide to go back home, but they find there is no wind. They conclude that they need a “blood offering,” so they carve an idol of Odin. Then they start randomly slaughtering each other in a bloody free-for-all. For at least a full minute, the screen shows nothing but swords hacking and slashing with blood and body parts flying everywhere.

Although there is evidence that, on some rare occasions, the Vikings did practice human sacrifice, the manner of the sacrifice depicted in the show is just bizarre and senseless. For one thing, the historical Vikings never sacrificed their own comrades; they sacrificed slaves or enemies whom they had captured. Furthermore, even if, for some bizarre reason, a group of Vikings were going to sacrifice one of their own comrades, they wouldn’t all just start hacking each other to pieces at random; they would designate one person as the sacrifice and kill that person in a ritual manner.

Unfortunately, many people don’t realize that these sorts of portrayals are just perverse screenwriters’ fantasies meant to attract viewers who like watching displays of gratuitous violence. Instead, they assume that medieval people—or at least medieval warriors—really were deranged berserkers who craved blood more than anything and were eager to slaughter their own companions at any moment.

ABOVE: Shot of Viking warriors slaughtering each other in a shower of blood for no apparent reason in the opening scene of the first episode of American Gods

Even many people who recognize that scenes like the one I have just described are ridiculous still accept the more general portrayal of medieval western Europe as an effectively lawless world in which people could go around murdering, raping, and pillaging without ever getting in any kind of trouble or facing any kind of legal repercussions as essentially accurate. This notion of a “lawless world,” however, is actually largely derived from twentieth-century western films and has very little to do with the historical Middle Ages.

It is true that, during the Early Middle Ages, laws and law enforcement were extremely localized and it is likely that, in some areas during some time periods, laws were not always well-enforced. Nonetheless, even in the rowdiest of places, laws and social norms still existed; a person couldn’t just walk into a tavern, stab a guy dead in front of everyone, and not get in any kind of trouble.

The High Middle Ages saw the development of powerful kingdoms that ruled over large swathes of land. Consequently, over the course of the High and Late Middle Ages, western European society became increasingly legalistic. In England, there were laws about what clothes people of various stations were allowed to wear and how much of which kinds of foods they were allowed to eat. Laws even dictated what kinds of leisure activities people were allowed to engage in. People who broke these laws were most often fined.

Not only was it illegal to go around raping and murdering people, but it was illegal to even carry a weapon in public unless you were a royal officer or a call to arms had been issued. (Similar laws had existed among the ancient Greeks.) This kind of strict weapons regulation would certainly never be tolerated in the contemporary United States.

Trial by combat was a real thing under English common law from at least the late eleventh century onwards, but it often ended with one side or the other forfeiting and only occasionally ended in someone actually getting killed. Trial by combat began to quickly fall out of popularity in the early thirteenth century and, by the end of the thirteenth century, it had been almost universally supplanted by trial by jury, which remained the dominant form of justice for the rest of the Middle Ages.

Torture really did exist during the Middle Ages, but, as I discuss in this article from November 2019, most of the bizarre and horrifying devices that are popularly believed to have been used for torture in medieval times—including the brazen bull, the iron maiden, the pear of anguish, and the Spanish tickler—either were never actually used for torture at all or did not exist during the Middle Ages.

ABOVE: Imaginative illustration by the Austrian artist Vinzenz Katzler from 1868 depicting a man being forced into an iron maiden. In reality, the iron maiden was invented as a hoax in the late eighteenth century and there is no evidence anyone was ever tortured in one.

Furthermore, people who claim that the Middle Ages was a time of exceptional violence frequently ignore instances of violence from ancient and modern times. For instance:

- In around January or February 415 BC, the Athenians slaughtered all the adult male inhabitants of the island of Melos and sold all the women and children into slavery, just because the Melians insisted on remaining neutral in the ongoing Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. This act of unprovoked cruelty was remembered in later times as a great atrocity.

- According to the first-century AD Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus in his Histories of Alexander the Great, after Alexander the Great conquered the city of Tyre in July 332 BC, he had 6,000 Tyrians executed, had an additional 2,000 Tyrian crucified along the beach, and sold nearly all the remaining Tyrian civilians (i.e. around 30,000 people, mostly women and children) into slavery.

- Julius Caesar’s conquest of Gaul, which lasted from 58 to 50 BC, is estimated to have resulted in at least 1,460,000 people dying in combat, at least eight hundred Gallic towns being destroyed, and at least a million Gauls being enslaved.

- The Thirty Years’ War, fought most in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, is estimated to have killed at least eight million people, including around one fifth of the total population of Germany.

- Acts of violence by white civilians against black people were extremely common in the United States, especially in the South, until the Civil Rights Movement in the mid-twentieth century. Even today, although lynchings and other acts of anti-black terrorism are at least less common than they once were, police brutality against black people remains a major issue.

- Between 1913 and 1923, the Ottoman Empire systematically murdered somewhere around 1.5 million ethnic Armenians, as well as between 450,000 and 750,000 ethnic Greeks and between 150,000 and 300,000 ethnic Assyrians in the Late Ottoman Genocides.

- Between 1933 and 1945, the Nazis systematically murdered roughly seventeen million people in the Holocaust, including Jews, ethnic Poles, Soviet civilians and prisoners of war, Romani people, people with physical and mental disabilities, political and religious dissidents, and gay men.

- The nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 by the United States are estimated to have killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people altogether and severely wounded thousands more. Most of the victims were civilians.

- Somewhere between seventy and eighty-five million people died in World War II altogether, making it the deadliest conflict in all of human history, far deadlier than any conflict that happened at any point in ancient or medieval times.

- The Second Congo War, fought mainly in Central Africa between 1998 and 2003, is estimated to have killed at least 5.4 million people and resulted in the displacement of at least two million more people, making it the deadliest conflict since World War II.

- In March 2020, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights estimated that the Syrian Civil War, which is still ongoing, had killed somewhere between 380,636 and 585,000 people, including at least 116,086 Syrian civilians.

These are just a few examples. When we look at the Middle Ages in this context, it becomes clear that whatever violence happened during that period was far from exceptional. Acts of outrageous violence have happened throughout human history and, unfortunately, they are unlikely to stop anytime soon.

Misconception #6: During the Middle Ages, everyone in western Europe was an orthodox Catholic and the Catholic Church had total control over what everyone believed.

For centuries, Protestant writers have portrayed the Middle Ages as a time when the Roman Catholic Church had complete control over what everyone believed. This portrayal has very much persisted. Even today, most people still imagine the Middle Ages as a time when everyone was fanatically Catholic.

There is some truth to this perception. It’s certainly true that, by the High Middle Ages, almost everyone in western Europe was at least nominally a practitioner of some form of Christianity. It’s also true that the church was very much concerned with matters of orthodoxy. At the same time, though, the popular perception of the Middle Ages as an “Age of Faith” isn’t entirely accurate.

Contrary to popular belief, during the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church’s control over what people believed was often tenuous at best, even when it came its own clergy. Most people today realize that there were people in western Europe during the Middle Ages who held beliefs that the church regarded as heretical. What most people don’t realize is just how common these beliefs really were.

Groups with teachings that the church considered heretical were common throughout western Europe throughout the medieval period. Examples of such groups include the Manichaeans, Arians, Montanists, Pelagians, Donatists, Paulicians, Tondrakians, Bogomils, Arnoldists, Patarines, Cathars, Brethren of the Free Spirit, Dulcinians, Waldensians, Amalricians, Lollards, Hussites, and countless others.

In many areas of western Europe during many periods of medieval history, heresy was more common than orthodoxy. The church knew they couldn’t prosecute everyone who held views that they regarded as heretical, so they focused on the leaders of these movements, who were preaching their views openly, and generally paid a lot less attention to the followers of these movements. Even then, some heretical leaders were executed, but many managed to evade prosecution.

ABOVE: Manuscript illustration from a copy of the Grandes Chroniques de France dated to between c. 1455 and c. 1460 depicting Amalrician leaders being burned at the stake. Burning heretics was a definitely real thing, but only a very small percentage of all heretics were actually burned.

There were undoubtedly many more people who weren’t members of larger heretical movements, but privately disagreed with the official teachings of the church. Notably, the church didn’t tend to concern itself much with enforcing orthodoxy on the peasantry and many medieval peasants believed some very unorthodox things.

Your average medieval peasant was illiterate and probably only had a vague impression of what it said in the Bible. They would have gone to church on Sundays and taken part in religious festivals, but, privately, probably held many beliefs that the church didn’t officially approve of. In many cases, they probably didn’t even realize that their beliefs were contrary to the church’s teachings because they didn’t even know what all the church’s teachings were.

As I discuss in this article from April 2020, traditional religious ideas lingered long after the advent of Christianity and religious syncretism flourished. Many traditional deities were superficially Christianized and became widely venerated as saints while retaining their traditional attributes and associations. In Ireland, for instance, people venerated Saint Brigid of Kildare, who has the same name and many of the same cult attributes as the ancient Celtic goddess Brigid.

Meanwhile, belief in thoroughly un-Christian supernatural beings, such as ghosts, elves, goblins, and household spirits remained widespread all across western Europe. (Indeed, as I note in this article from June 2020, many people in Europe and North America still believe in these entities today in the twenty-first century.)

ABOVE: Woodcut from between c. 1500 and c. 1520 depicting Saint Brigid kneeling before the Man of Sorrows

Expressions of religious skepticism in the Middle Ages seem to have often gone unpunished and undocumented, but records from areas and time periods where authorities were unusually dedicated to rooting out heresy and blasphemy can give us an impression of what must have been happening on a much wider scale.

In 1988, a scholar named John Edwards published an analysis of a “book of declarations” made by the Spanish Inquisition documenting 444 statements made in Spain by people of varying statuses between the year 1486 and the year 1500 that were deemed heretical or blasphemous.

Some of the statements recorded in the book seem relatively tame to present-day Christians, but were seen as shockingly heretical to the Inquisition authorities. For instance, in around 1488, a peasant woman named Juana Perez is reported to have said that good Jews and Muslims would attain salvation. This is an idea that many liberal Christians today accept. At the time, though, it went against the official orthodoxy, which was that only Christians could attain salvation. Juana Perez wasn’t alone in her universalism; eight men were prosecuted with her for making similar statements.

At some point during the Granada War (lasted 1482 – 1492), a miller named Diego de San Martin complained to a farmer named Gil Recio that there was no rain. Gil is reported to have replied, “How do you expect it to rain when the king is going to take the Moors’ home away, when they haven’t done him any harm?” Diego replied that it was good for a Christian king to take land away from Muslims. Gil replied, “How does anyone know which of the three laws God loves best?”

Some of the other statements recorded in the book are even more heretical. In 1498, a man named Diego de Barrionuevo is reported to have said, “I swear to God that this hell and paradise is nothing more than a way of frightening us, like people saying to children, ‘Avanti coco’ [‘The bogeyman will get you’].”

Shockingly, the book contains record of flagrantly anti-religious statements made even by members of the clergy. For instance, in around 1485 in Aranda, a local cleric named Diego Mexias is reported to have said that heaven and hell do not exist, that there is no afterlife at all, and that “there is nothing except being born and dying, and having a nice girlfriend and plenty to eat.”

One thing that is remarkable about these statements is that they were made openly, without any apparent fear of prosecution; in other words, these people really didn’t expect the Spanish Inquisition. This gives us good reason to think that doubts like these were probably being voiced by various people all over Europe throughout the Middle Ages. We only know about the cases listed here because the Spanish Inquisition was particularly diligent in prosecuting heretics.

Although we lack direct evidence, we have reason to suspect that there were some medieval scholars who privately had doubts about the existence of God. One interesting piece of evidence is the fact that medieval theologians such as Anselm of Canterbury (lived c. 1033 – 1109) and Thomas Aquinas (lived 1225 – 1274) went to great effort writing arguments attacking atheism and defending the existence of God.

No one writes an argument against a position unless it is at least conceivable that someone might support that position. Therefore, the fact that medieval theologians felt the need to compose arguments for the existence of God seems to demonstrate that either these theologians believed that there were other scholars out there who doubted the existence of God or the theologians themselves had private doubts about the existence of God that they were trying to assuage.

I think it is clear at this point that the modern impression that medieval western Europe was an orthodox Catholic monolith is mistaken.

ABOVE: Altarpiece of the medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas painted by the Italian painter Carlo Crivelli (lived c. 1430 – 1495). If doubt did not exist during the Middle Ages, why did Thomas Aquinas spend so much time formulating arguments for the existence of God?

Misconception #7: The Middle Ages were a time of technological stagnation when nothing new was invented.

Tied in with the misconception that the Middle Ages were a time when the Pope had total control over what ordinary people believed is the misconception that they were a backwards time of technological stagnation.

It is true that the Early Middle Ages—the period of medieval history that some historians think the term “Dark Ages” can legitimately be applied to—were indeed a time of little innovation. They were not a period of total stagnation, however. Furthermore, the High and Late Middle Ages were actually periods of great technological and scientific progress.

Here is a list of a few inventions that either originated in western Europe during the Middle Ages or came into use in western Europe during the Middle Ages:

- The lateen sail was most likely invented in the eastern Mediterranean in around the first century BC, but it did not come into widespread use until around the sixth century AD.

- The heavy iron moldboard plow was first invented in China in around the first or second century AD. It was in use in the Po Valley of northern Italy by the mid-seventh century AD and in use in southwest Germany by the early eighth century AD. It was in use in Britain by the ninth century AD. It is unclear whether the heavy plow was invented independently in both China and Europe or was invented in China and spread to Europe through cultural diffusion.

- The horse collar was first invented in China in around the late fifth century AD. It first appears in Europe in the late eighth century AD. It is unclear whether it spread from China to Europe or was invented independently in both places. In any case, the horse collar changed western European society because it allowed horses to be used for ploughing and sowing fields, rather than oxen. Horses could apply twice as much power as oxen, they had much greater endurance, and they could work more hours each day.

ABOVE: Early European depiction of the padded horse collar in a manuscript illustration from c. 800 AD

- Horizontal windmills were first invented in the Middle East, possibly as early as the seventh century AD. The vertical windmill, however, was first invented in northwestern Europe in around the twelfth century AD. Vertical windmills were more advantageous because they could turn to face the direction of the wind; whereas earlier horizontal windmills could not.

- The first sternpost-mounted rudders were invented in China in around the first century AD or thereabouts, but the sternpost-mounted pintle-and-gudgeon rudder was invented in western Europe in around the twelfth century AD. It is unclear whether European pintle-and-gudgeon rudders were influenced by earlier Chinese and Arab sternpost-mounted rudders, since they use a different method of attachment.

- The first mechanical water clocks were invented in Islamic Spain in the eleventh century AD; the first fully mechanical clocks were invented in Christian-ruled northwestern Europe, possibly in around the late twelfth century AD.

- The first eyeglasses were first invented in northern Italy in around 1290 or thereabouts. They had not been invented anywhere else previously. In a sermon delivered in Florence on 23 February 1306, the friar Giordano da Pisa proclaimed, as translated by Vincent Ilardi, “It is not twenty years since there was found the art of making eyeglasses, which make for good vision, one of the best arts and most necessary that the world has. And so short a time that this new art, never before extant, was discovered.”

ABOVE: Painting by the German Gothic painter Conrad von Soest from 1403 depicting an apostle reading the gospel, wearing eyeglasses

- The dry compass was invented in around the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century. Traditionally, it is said to have been perfected by the Italian mariner Flavio Gioja.

- The ancient Romans developed the first glass mirrors in the first century AD, but these mirrors were either concave or convex, resulting in reflections being distorted. Advances in glassmaking technology in the High and Late Middle Ages, however, allowed for the creation of flat glass mirrors that did not distort the image being reflected.

- The earliest known moveable type printing press was invented in China in around 1040 AD. The movable type printing press was independently developed in Germany, however, between 1439 and 1450 by the German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg (lived 1400 – 1468), working in collaboration with several associates. The invention of the printing press revolutionized European society because it allowed writing to be mass-produced for the first time in western history. The printing press was such a monumental invention that its invention is often considered to mark the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Early Modern Era.

Some of these inventions are still used today in almost exactly the same forms as when they were first invented back during the Middle Ages.

We really ought to give medieval inventors vastly more credit than we have given them. We should stop disparaging the Middle Ages as a time of utter backwardness and instead recognize the incredible achievements that the people of the Middle Ages have given us. If you have ever read a printed book, worn eyeglasses, or looked in a glass mirror, thank a medieval inventor.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of a modern recreation of the Gutenberg printing press. Everyone seems to forget that the printing press, which fundamentally changed the course of human history, was a medieval invention.

Misconception #8: Medieval doctors were unusually ignorant compared to doctors in earlier and later eras.

There is some truth to the popular belief that people in the Middle Ages knew very little about medicine. This isn’t really their fault, though, since the Greeks and Romans who came before them knew very little about medicine either. In fact, most of the medieval practices that modern people find the most abhorrent came from the Greeks and Romans.

Let’s look at what is perhaps the most notorious medieval medical practice: bloodletting. Medieval doctors really did bleed people, but the practice actually originated in ancient Greece. Bloodletting is rooted in the ancient Greek medical theory of humorism, which held that there were four fundamental bodily fluids, or “humors”: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm.

In antiquity and the Middle Ages, it was widely believed among doctors that many diseases were caused by an imbalance of these four “humors.” In many cases, doctors believed that the humors could be brought into balance by removing a moderate quantity of blood.

ABOVE: Scene from an Attic red-figure vase painting dated to between c. 480 and c. 470 BC depicting a doctor performing a bloodletting

ABOVE: Late thirteenth century French manuscript illustration of a doctor performing a bloodletting on a young man

Many people today believe that bloodletting was an extremely deadly procedure that only made people die faster. In some cases, this may have been true, but, in most cases, it was probably neither helpful nor harmful. A normal person can lose a moderate amount of blood without any ill effects. Medieval doctors recognized that it was dangerous to extract blood from people who were elderly or extremely sick and they also recognized that extracting too much blood could be deadly.

A medieval patient was unlikely to die of bloodletting, unless the doctor performing the procedure was horribly incompetent or he was intentionally trying to kill the patient. The procedure was painful and not medically helpful, but many patients probably felt better afterwards due to the placebo effect.

This perhaps explains why bloodletting remained a common practice in mainstream medicine until as late as the early twentieth century. The fourteenth edition of the leading medical textbook Principles and Practice of Medicine, published in 1942, still recommended bloodletting as an appropriate treatment for pneumonia. That means there are people still alive who can remember a time when bloodletting was still used in mainstream medicine.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of a man performing a bloodletting on a woman taken in 1922

One artifact that is often cited as evidence that medieval doctors were stupid is the infamous plague doctor costume. To give just one example of this, in his opening monologue for the 30 September 2019 episode of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, Stephen Colbert tells this joke about plague doctors:

“The president of the United States just tweeted the phrase “pro-shark media,” which means we’ve officially entered the dumbest time in human history, beating the previous dumbest time, when we thought a spooky bird mask could protect you from the black plague. Congrats bird mask!”

The camera immediately cuts to person wearing a plague doctor costume dancing to funky dance music.

As I explain in this article I published in March 2020, however, there are two huge problems with the idea that plague doctor costumes are evidence of medieval stupidity. The first problem is that the iconic, bird-beaked plague doctor costume we are all familiar with today isn’t actually medieval. There were doctors in the Middle Ages who wore various kinds of outfits to protect themselves from the plague, but the standard, bird-beaked costume was actually designed by the French physician Charles de Lorme in 1619—long after the end of the Middle Ages.

Furthermore, the plague doctor costume was actually a step in the right direction. Most people today incorrectly believe that the costume was designed to look super creepy to “scare away” the plague. In reality, the outfit had nothing to do with “scaring” anything away and was more like the Early Modern predecessor to the hazmat suit.

In the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, it was widely believed among doctors that diseases were caused by “miasmata,” or infectious vapors in the air. The idea behind the plague doctor costume was to completely cover the doctor’s body, so that the miasmata could not penetrate. The costume consisted of boots, leggings, an overcoat, gloves, and a hood—all made of thick Moroccan or Levantine leather that had been covered in wax to repel miasmata and bodily fluids.

Each part of the suit connected directly to the rest of it, leaving no skin exposed. The doctor’s eyes were protected by glass goggles. The beak was filled with herbs or other aromatic substances that were supposed to purify the air the doctor breathed and prevent him from breathing in miasmata. The fact that it happened to be shaped like a beak was irrelevant to its intended purpose.

Today we know that the miasma theory of disease is incorrect and that diseases are actually spread by pathogens. Nonetheless, the plague doctor outfit probably did provide doctors some measure of protection from the plague since many measures that were intended to keep out miasmata probably did a decent job of keeping out fleas and bacteria.

The biggest flaw in the costume is the beak full of herbs, since the beak had holes in it for the doctor to breath through and the herbs inside probably did nothing or very little to purify the air the doctor breathed, meaning the doctor could easily inhale airborne droplets bearing the Yersinia pestis bacterium, allowing him to potentially contract pneumonic plague.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of a surviving seventeenth-century plague doctor mask from Austria or Germany on display in the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin

There have undoubtedly been great advances in medicine in the past hundred years. Smallpox, a disease that killed hundreds of millions of people, has been completely eradicated. Polio, a disease that has killed millions and left millions more crippled for life, has been nearly eradicated. The bubonic plague, which historically wiped out hundreds of thousands of people at once, is now rare and easily treatable with antibiotics. Critics of medieval medicine, however, often forget that, despite how far medicine has come, it still has a very long way left to go: