Adam Ruins Everything is a comedy television series on TruTV starring comedian Adam Conover. It has been on air since September 2015 and has had, to date, three seasons, amounting to a total of sixty-five episodes. The basic premise of the show is that Adam Conover is an obnoxious know-it-all who cannot help ruining everyone around him’s favorite things by revealing to them the dark truths and common misconceptions surrounding them.

This premise provides a sort of framing narrative for a series of information-based comedy segments, which make up the bulk of each episode. Each episode usually consists of three segments debunking common misconceptions related to a particular topic, followed by a final “positive takeaway” segment in which Adam tries to make the audience feel better by putting a positive spin on everything he has said throughout the episode. Along the way, Adam cites various sources (some more reliable than others) and calls in people identified as experts to testify.

In general, most of the show’s main points are usually broadly correct. The show clearly really does strive for factual correctness, as demonstrated by their repeated warnings that the show is fallible and their multiple “corrections segments.” Sadly, they do not always live up to their aspirations. Often the errors on the show are errors of omission resulting from the fact that it is only a thirty-minute show and they try to cram no less than three different debunking sessions into each episode, which results in a series of extremely rushed information segments that end up leaving out a lot of really important information.

An entertainment show, not an educational show

One major problem with the show is that it seems to be conflicted between trying to present serious factual information while still keeping the show funny, entertaining, and suspenseful. Adam will frequently make an extremely shocking and radical claim right before a commercial break to keep the audience paying attention and then tone down that claim when the show comes back after the break. Unfortunately, since the viewer has already heard the wildly exaggerated claim from before, they remember the more sensational claim rather than the more nuanced explanation that follows it.

Unfortunately, this “clickbait” quality of the show seems to be inevitable for commercial television. In fact, most historical documentaries—even the really good ones from Smithsonian Channel or PBS—do something very similar; it seems as though, before every commercial break, they always announce some sensational possibility, but, then, when the show comes back, they ultimately reject it and come to a more reasonable conclusion. One thing that makes Adam Ruins Everything different is that they do not usually refute the sensational claim made before the break or even clearly state that they were exaggerating.

ABOVE: Promotional image for the show

Very little nuance

Another problem is that the comedic nature of the show unfortunately tends to leave very little room for nuance because comedy, by its very nature, is not very good at conveying nuance. In order to keep the show interesting, the show tries to insert a joke after every statement and sometimes those jokes can distort what was actually just said and leave a very inaccurate impression of it.

Another problem is that, as plenty of others have already pointed out, the show clearly always has an agenda. Of course, lots of shows have an agenda and there is really nothing inherently wrong with them having an agenda, but they should probably be more open about it. They frequently present opinionated statements as though they are objective facts. Also, sometimes, their agenda can lead them to make clearly inaccurate, over-the-top claims.

For instance, in season one, episode twenty-one, titled “Adam Ruins Drugs,” they did a segment on marijuana. They could have made an entirely reasonable case that marijuana is no more dangerous than tobacco, but instead they made the strident claim that marijuana is “essentially harmless.” Really? “Essentially harmless”? Not according to the American Lung Association.

In fact, almost immediately after making this extremely bold claim, Adam partially contradicted it, accurately pointing out that it can be harmful to the development of people under the age of twenty-five. He neglected to mention, however, the fact that smoking marijuana is extremely unhealthy for a person’s lungs or that it can often lead to lung disease and lung cancer. He also neglected to mention other side effects of using the drug. Clearly, “essentially harmless” was a gross exaggeration.

ABOVE: Screenshot of Adam attempting to light a joint from the “Adam Ruins Drugs” episode

My area of study is classical history. The show has actually ventured into this territory on several occasions and, although the points they make are usually broadly correct, they frequently make errors or exaggerations. Here is a debunking of some of the show’s major mistakes in relation to classical history that I have noticed:

Errors about ancient history in “Adam Ruins Weddings”

In season one, episode fifteen, titled “Adam Ruins Weddings,” Adam claims that, in ancient times, people were not supposed to love their spouses and that loving one’s spouse was considered “weird and irresponsible.” It is true that, it was not generally believed in antiquity that a person needed to love their spouse. It is also true that, in some elite circles during some time periods, excessive affection for one’s spouse could be seen as problematic in some circumstances.

Adam, however, neglects to mention that many people clearly did love their spouses and that this was generally seen as a good thing. This is evidenced, for instance, by the fact that there was a whole genre of ancient Greek romance novels, such as Daphnis and Chloe by Longos of Lesbos and Leukippe and Kleitophon by Achilleus Tatios, which idealize loving marriages. If loving one’s spouse were really considered “weird and irresponsible,” as Adam says in the segment, then what would we be expected to make of the thriving genre of novels like these?

This claim by Adam about people in antiquity not being supposed to love their spouses is immediately followed by an unfortunate joke about the Romans’ supposed love for orgies, which, as I explain in this article I wrote, is actually a modern misconception. We have no reliable evidence that orgies were at all common in ancient Rome and the idea that they were is largely the result of modern uncritical readings of unreliable and unrepresentative written sources, uncritical Victorian interpretations of archaeological evidence, and egregiously inaccurate portrayals in modern Hollywood films.

ABOVE: Screenshot of a caricature of an ancient Roman from the episode “Adam Ruins Marriage” saying “Now, who’s down for an orgy?”

The misquotation of Socrates in “Adam Ruins the Internet”

In season one, episode twenty-four, titled “Adam Ruins the Internet,” Adam quotes the Greek philosopher Socrates as having said that “[The written word] will create forgetfulness in the learner’s souls.” This is actually a bad paraphrase of a real quote attributed to Socrates by Plato in his dialogue Phaidros. It is a bad paraphrase because Adam completely misses the nuance of what Plato was actually writing here. As I explain in this article I wrote, this quote is not Plato saying that writing is all bad, but rather him merely saying that every great invention has negative consequences that the inventor cannot possibly foresee, as is evidenced by the context of the passage.

ABOVE: Scene from the episode with Socrates

Errors about ancient history in “Adam Ruins Christmas”

In season one, episode twenty-six, titled “Adam Ruins Christmas,” Adams quickly tells a completely butchered version of the traditional story of Saint Nicholas’s generosity to three girls without dowries. He says, “Jolly old Saint Nick loved giving gifts, especially to young girls… He would sneak into their houses in the middle of the nights and leave gold in their stockings so they wouldn’t become prostitutes.”

In the actual, traditional version of the story, however, which is first attested in an account by Michael the Archimandrite in his hagiography of Saint Nicholas, written in around the ninth century AD or thereabouts, this is not how the story goes at all. The way it actually goes is that there was a man who was extremely poor and had three daughters of marriageable age, but could not afford to pay their dowries.

Without dowries, the girls would be forced to become prostitutes in order to survive. Nicholas, however, went to the home on three consecutive nights and threw one bag of gold in through the window each night to provide a dowry for each of the daughters. There is no hint of pedophilia in this story at all and, in the earliest recorded version, Saint Nicholas does not even actually go inside the home. I do not know whose retelling of this story the writers for the show heard, but, somewhere along the line, the story was clearly garbled.

ABOVE: Screenshot of Saint Nicholas saying “No need for streetwalking, my dear” from the “Adam Ruins Christmas” episode

Errors in Adam’s debunking of Roman gladiators

In season two, episode twenty, titled “An Ancient History of Violence,” the first segment is a broadly accurate debunking of popular culture depictions of gladiatorial combat in which Adam explains how, for most of Roman history, deaths in the arena were far less common than is often portrayed, because gladiators were a major investment for their owners and the Romans took measures to keep them alive so they could be used to make more money.

Unfortunately, Adam overstates his case a bit and makes it almost sound like gladiatorial combat was completely safe and deaths were almost unheard of when, in fact, around one in ten gladiatorial matches are estimated to have ended in a death. That is still better than most movies and shows portray, but is still a far, far higher death rate than for any modern sport. (You can read my own article debunking misconceptions about gladiators here.)

ABOVE: Scene from the gladiators segment of the episode on violence in the ancient world

Errors and glaring omissions in Adam’s portrayal of Boudicca

The second segment in that same episode is a clearly well-intentioned, but deeply flawed retelling of the story of Boudicca, who led an uprising against the Romans in Britain that lasted from c. 60 to c. 61 AD. In this segment, Adam squarely blames the Roman cruelty in Britannia on the Emperor Nero. This is not accurate, however; while Nero was certainly an unpleasant character in many ways, he never visited Britannia and probably was not actively involved in the governance of the territory. Instead, the cruelty there was more the result of the Roman officials in Britannia itself.

The segment also totally glosses over Boudicca’s own brutality, which I go into great detail discussing in this article I published. Boudicca is known to have razed entire cities to the ground and tortured and massacred their inhabitants. It is understandable why she did this, given what the Romans had done to her, but it is still important not to gloss over it. During her bloody rampage, Boudicca is estimated to have brutally tortured and massacred tens of thousands of innocent civilians.

The Roman writers Tacitus (lived c. 56 – c. 120 AD) and Cassius Dio (lived c. 155 – c. 235 AD) record that Boudicca totally massacred the civilian populations of the cities of Camulodunum (modern Colchester), Londinium (modern London), and Verulamium (modern St. Albans)—which, combined, had an estimated population of between 70,000 and 80,000 people.

The archaeological record confirms that Boudicca’s forces utterly destroyed these three cities, burning them to the ground, leaving nothing but a thick layer of ash behind. This evidence lends a great degree of credence to the Roman sources claiming that her forces massacred the inhabitants of these cities.

ABOVE: Screenshot of the cartoon Boudicca from Adam’s segment on her

According to Tacitus and Cassius Dio, Boudicca showed no mercy whatsoever to the women, children, or the elderly. In fact, Cassius Dio records that she had a particularly cruel method of treating prominent Roman noblewomen; supposedly, she had their breasts cut off and sewn to their mouths to make it look like they were eating them. Then she had them impaled on spikes.

Cassius Dio was writing much later than Tacitus, who does not mention this story, so this account must be considered suspect, but it is still plausible based on what we know from the archaeological record. Also, we have reason to suspect that Tacitus may have had some degree of sympathy for Boudicca’s cause and it is possible he may have intentionally omitted mention of Boudicca’s worst atrocities in order to portray her more favorably.

I will not deny that Boudicca makes an awesome heroine for standing up to the Romans, but Adam really should have at least mentioned the between 70,000 and 80,000 civilians that she slaughtered without mercy. By omitting nearly all mention of Boudicca’s own brutality, he presents a heavily one-sided narrative much like the narratives he himself criticizes elsewhere.

Finally, at the end of the segment, for some bizarre reason, a group of Celts are shown praying around a stone Celtic cross, which is anachronistic and inaccurate, because Christianity had not yet been introduced to Britannia in the time of Boudicca and the Celtic cross did not develop until the ninth century AD, nearly a thousand years after Boudicca. I doubt the appearance of this cross is likely to give anyone watching the segment the misimpression that the Celts in the first century AD were already Christian, but it does look incredibly weird to see the Celts of this time period portrayed worshipping around a stone cross.

ABOVE: Shot of the animated Celts worshipping around a stone cross from the end of Adam’s segment on Boudicca. Apparently Adam thinks the Celts in c. 61 AD were Christian…?

Errors in Adam’s debunking of ancient Sparta

In that same episode, the third segment is a broadly accurate debunking of the egregiously historically inaccurate film 300. I have written my own debunking of the film here, which I highly suggest anyone who has watched the film should read. Unfortunately, while debunking the errors in the film, Adam also makes a number of serious errors himself.

For instance, Adam’s portrayal of life in ancient Sparta is at best an absurd caricature of the heavily mythologized version of the story that has been preserved in the surviving ancient sources, which were almost exclusively written by non-Spartans. In other words, Adam is taking an already probably fairly inaccurate portrayal and egregiously oversimplifying it to make Sparta look as evil as possible.

For instance, Adam portrays Sparta as a brutal totalitarian state, comparing it to modern-day North Korea. This is only a partially accurate portrayal. While it is certainly true that Sparta was not exactly a true and complete democracy in the modern sense, it did at least have some at least nominally democratic institutions. The main administrators in ancient Sparta, for instance, were the ephors, who were democratically elected by the apella, an assembly made up of all adult male Spartan citizens.

Mind you, only adult male Spartan citizens (who made up an extremely tiny minority of the total Spartan population) were allowed to participate in this democracy. Nonetheless, ancient Sparta was at least partially democratic in some sense. It was certainly a very flawed democracy in a lot of ways, but it was still definitely more democratic than North Korea.

Adam also claims that every Spartan boy was “forced to become a concubine and were made to perform sexual services for former soldiers.” This is presumably a reference to the ancient Greek practice of pederasty. Adam, however, egregiously oversimplifies what was actually an extremely complicated ancient Greek cultural practice and portrays it as far more mandatory than it probably really was. For more information about this, here is an article I wrote on the subject in June 2019.

ABOVE: Cartoon depiction of a Spartan boy being “forced to become a concubine” from Adam’s segment on ancient Sparta and the Battle of Thermopylai

Errors in Adam’s portrayal of Herodotos

In addition to not being completely accurate about life in ancient Sparta, I also feel that Adam is very unfair in this segment towards the ancient Greek historian Herodotos of Halikarnassos (lived c. 484 – c. 425 BC), whom he blames for the entire concept of a civilized “west” versus an exotic, barbaric “east.”

While it is true that Herodotos is guilty of exoticizing the Persians and other non-Greek peoples to a certain extent, he actually inherited this conception of non-Greek peoples as “barbarians” from the larger Greek culture that surrounded him. Furthermore, Herodotos does not speak in term of “the west” versus “the east,” but rather in terms of “Greeks” versus “barbarians” (i.e. non-Greeks). The concept of a larger “west” that included Greeks but also non-Greek “western cultures” did not exist in Herodotos’s time and is, in fact, an invention of later writers.

Adam also blames Herodotos for the entire biased narrative behind the movie 300 and its portrayal of the Battle of Thermopylai. I think this is also very unfair to Herodotos. Sure, Herodotos was not a fan of the Persian invasions, but, if you actually read his Histories, he does not portray all Persians as evil. On the contrary, Herodotos portrays Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, as a paragon of wisdom and virtue. He even ends the book with a quote from Cyrus, strongly implying that his fellow Greeks could learn a thing or two from him.

Even Herodotos’s portrayal of Xerxes I is not entirely negative. While 300 portrays Xerxes as saying “I would gladly kill any of my own men for victory,” there is actually a very famous scene in Book Seven of Herodotos’s Histories in which he portrays Xerxes as breaking down in tears at the realization that all his men will be dead in a hundred years. Herodotos probably included this scene in order to humanize Xerxes and show that even the all-powerful, barbarian king was capable of compassion.

It is worth noting, as I do in this article I wrote in September 2019, that Herodotos actually grew up in the city of Halikarnassos, which, at the time, was part of a Persian satrapy ruled by Queen Artemisia I of Karia. Thus, Herodotos actually grew up under indirect Achaemenid rule. Meanwhile, Herodotos gives Artemisia I an extremely favorable portrayal in his Histories, even though she fought for the Persians. Herodotos’s allegiances ultimately lay with the Greeks, but his background was a lot more complicated and nuanced than Adam makes it sound in the episode.

Adam remarks in the episode on the fact that 300 includes some lines that are adapted from quotes from Greek historians like Herodotos, implying that this indicates that the film was extremely faithful to the ancient historians’ portrayal of the Battle of Thermopylai. This could not be further from the case, though. The handful of lines in the film that were loosely adapted from Herodotos and other Greek writers are just for flavoring and, aside from those lines, the film barely resembles the ancient accounts of the battle at all.

It is also worth noting that Herodotos was actually criticized in antiquity for portraying the Persian too positively and for not portraying the Greeks as infallible. The Greek Middle Platonist philosopher Ploutarchos of Chaironeia (lived c. 46 – c. 120 AD) even attacked Herodotus as a Persian-sympathizer in his essay “On the Malice of Herodotus,” calling him a “φιλοβάρβαρος” or “barbarian-lover.”

Was Herodotos biased? Yes, of course he was. Is he solely responsible for the egregiously inaccurate portrayal of the Persians in the film 300? No. In fact, only an extremely tiny portion of the blame for that film can be rightly assigned to Herodotos. The vast majority of the blame for 300 rests on the backs of the people who actually made the film, especially Frank Miller (who wrote the comic book the film is based on) and Zack Snyder (who was the director and head writer for the film).

ABOVE: Shot of the cartoon Herodotos dictating his Histories to a scribe, as portrayed in the Adam Ruins Everything segment on the Spartans and the Battle of Thermopylai

Errors and glaring omissions in Adam’s portrayals of Galen and Vesalius

In season two, episode twenty-one, titled “The Copernican Ruin-aissance,” the second segment centers on the Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius. Again, while the segment is broadly accurate to my knowledge, I think that Adam is a bit unfair to the ancient Greek anatomist Galen (lived c. 129 – c. 200/c. 216 AD).

Adam mocks the fact that Galen had never dissected an actual human body and had instead only dissected other animals and assumed that humans must be similar. Unfortunately, he omits mention of the crucial fact that the reason for this was because dissecting human corpses was illegal in Egypt at the time when Galen was alive. In other words, Galen was doing the best he possibly could under his circumstances.

Furthermore, Adam neglects to mention that, like Vesalius, Galen himself actually went against inaccurate statements about anatomy made by earlier writers. For instance, centuries before Galen, the philosopher Aristotle (lived 384–322 BC) had incorrectly concluded that the brain was just an organ for heat ventilation and that the seat of consciousness was the heart, but Galen correctly concluded that the brain was the true seat of consciousness—not the heart. Galen deduced this by observing that all the nerves from the sensory organs are connected to the brain, in particular the optic nerve.

Finally, Adam neglects to mention that Vesalius made a lot of serious errors as well. Vesalius corrected some of Galen’s errors, but it was up to later anatomists to correct Vesalius’s errors. In other words, Galen and Vesalius both made mistakes, but they are also both responsible for forwarding the field of anatomy. It is unfair of Adam to portray Galen as a hack and Vesalius as a brave hero; they both made important contributions to our modern scientific understanding of the human body.

ABOVE: Shot of the animated Andreas Vesalius from the episode on the Renaissance

Adam’s error about razors in “Adam Ruins a Night Out”

In season three, episode six, titled “Adam Ruins a Night Out,” in the first segment, Adam claims that, prior to the invention of the safety razor in the early 1900s, “most men either went to a barber or didn’t shave at all.” I do not know how true this statement is for modern history, but I do know that, as far as ancient history goes, it is not accurate. It was the norm for males slaves in ancient Greece to go clean-shaven and we can be reasonably sure that most of these slaves probably could not afford to go to a barber, so the logical conclusion is that they must have been shaving their beards themselves.

Meanwhile, in Hellenistic Greece and the Roman Republic, it was the norm for all men—not just slaves—to go clean-shaven. Some of these men may have gone to barbers, since we know that barbers did exist in ancient Greece and that many free men would have been able to go to them. Nonetheless, many of them presumably shaved themselves.

ABOVE: Screenshot of a terrified man frightfully contemplating the dangerous idea of shaving his beard from Adam’s segment on hair removal

After this, Emily claims that Gillette convinced women that they had to shave “for the first time in history” and that “up until 1920, most women didn’t shave at all.” Once again, I do not know how accurate this statement is with regard to modern history, but I do know that it is not accurate as far as ancient history is concerned.

Judging from pictorial depictions of nude women from ancient Greece and Rome, women in ancient Greece and Rome seem to have commonly engaged in some form of depilation (i.e. removal of body hair). Depilation is also referenced in a number of surviving ancient Greek and Roman texts.

For instance, in the comedy Women at the Thesmophoria Festival, written by the Athenian comic playwright Aristophanes (lived c. 446 – c. 386 BC) and first performed in Athens in 411 BC, a relative of the playwright Euripides tries to disguise himself as a woman and, as part of his disguise, he is required to depilate all his body hair, including his pubic hair.

This is just one of a number of references to female depilation in ancient Greek and Roman texts. Ancient Greek and Roman women may not have “shaved” in the same way that women typically shave today, but many of them did remove their body hair somehow. If vase paintings and sculptures are anything to judge by, many men seem to have done the same thing.

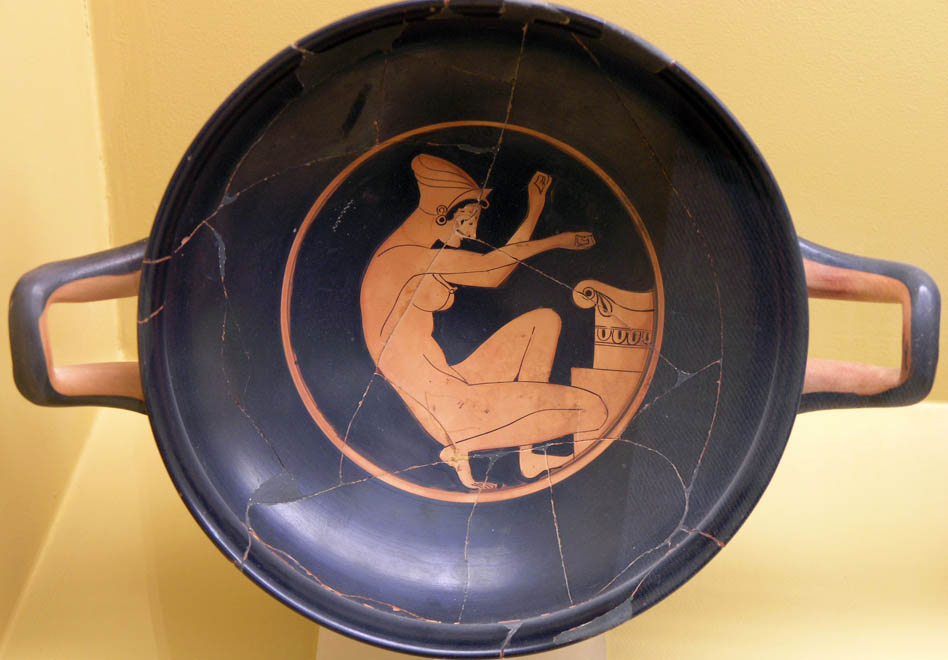

ABOVE: Tondo from an Attic red-figure kylix dated to between c. 510 and c. 500 BC on display in the Agora Museum in Athens depicting a nude woman kneeling before an altar. Notice that, at least as far as we can tell from the painting, she does not seem to have body hair.

Conclusion

These should hopefully give you an impression of the kinds of errors the show is making. This list is not by any means intended to be comprehensive in any way; these are just examples of mistakes that I noticed.

Ultimately, I actually like the show and I think it is, in spite of its flaws, overall a force for good. Broadly speaking, the show is usually fairly accurate and they have boldly tackled a lot of misconceptions that have always gotten on my nerves. The worst problems with the show are that they frequently overstate things, their agenda can sometimes lead them to not represent the other side fairly, and sometimes they just make simple, honest mistakes.