The ancient Greek historian Herodotos of Halikarnassos is renowned today as the “Father of History,” a title that was first conferred on him by the Roman orator Marcus Tullius Cicero (lived 106 – 43 BC) in his dialogue On the Laws. Herodotos is often credited with having been the first person to methodically collect and critically analyze different accounts of events from different sources, compile them into a detailed historical narrative, and attempt to assess the causes of those events and analyze the motives and politics behind them.

Herodotos did these things in a book in nine volumes titled Ἱστορίαι (Historíai), meaning “researches” or “inquiries,” describing his research on the Greco-Persian Wars and their historical context. It is from the title of Herodotos’s book that we have gotten our English word history. Ironically, even though Herodotos has contributed so much to our understanding of history, very little is known about Herodotos’s own, personal history. In this article, I intend to discuss what is known about Herodotos’s own life.

Predecessors to Herodotos

Although Herodotos is the earliest writer who is known to have definitely approached history in a systematic manner, dealing with multiple accounts of events and assessing their accuracy, he was certainly not the first person ever to write about historical events. Herodotos did have predecessors. We have surviving texts and inscriptions dating all the way back to ancient Sumer that could, in some sense, be regarded as “history.” For instance, we have many surviving inscriptions written by various Near Eastern kings boasting of their exploits and conquests.

Among the earliest surviving works of this variety is the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, which dates to between c. 2254 and c. 2218 BC and bears an inscription in Akkadian boasting of Naram-Sin’s victory over Sidur and Situni, two princes of the Lulubi. This inscription, however, like all other inscriptions of its variety, is more royal propaganda than real, honest history.

ABOVE: Photograph of the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin

Similarly, before Herodotos, there were plenty of chroniclers who wrote about historical events. For instance, the Sumerian King List is a text written in Sumerian that has been dated to the very beginning of the second millennium BC that lists various kings of Sumerian city-states. Many of these kings are legendary figures, not historical ones. Additionally, the text gives very little in the way of narrative, since it is mostly just a list of names and dates.

ABOVE: Photograph of a stone tablet on display in the Ashmolean Museum dating to between c. 1827 and c. 1817 BC, inscribed with the text of the Sumerian King List

Another work dealing with historical matters that is traditionally thought to predate Herodotos is the so-called “Deuteronomistic History,” which is composed of the Book of Joshua, the Book of Judges, the First and Second Books of Samuel, and the First and Second Books of the Kings. The Deuteronomistic History is usually thought to have been originally written during the reign of King Josiah of Judah (ruled c. 640 – c. 609 BC) and later revised and edited during the Babylonian Exile (lasted c. 597 – c. 539 BC).

The Deuteronomistic History gives a very long, detailed narrative of the history of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Most of this account, however, is now widely regarded by scholars as a mixture of fiction and legend. Furthermore, unlike Herodotos in many cases, the Deuteronomistic History does not give different accounts of the events from different sources.

ABOVE: The Judgement of Solomon, painted in 1617 by the Dutch Baroque paitner Peter Paul Rubens, depicting a famous scene from the Deuteronomistic History that is unlikely to have happened historically

There were also other Greek writers before Herodotos who wrote about historical events, including Dionysios of Miletos, Charon of Lampsakos, Hellanikos of Lesbos, Xanthos of Lydia, and Hekataios of Miletos. Only tiny fragments of the writings of these authors have survived, however. Many of these earlier Greek writers seem to have included mythology as part of their history and none of them seem to have written works on the sheer scale of Herodotos’s Histories.

Of all these writers, Hekataios of Miletos (lived c. 550 – c. 476 BC) is by far the best-attested. He is known to have written two works: the Periodos Ges, a treatise on geography spanning two volumes, and the Genealogiai, a treatise on mythological genealogies in four volumes. Some have argued that Hekataios deserves the title of the “Father of History” rather than Herodotos. We know very little, however, about Hekataios’s methodology; whereas, with Herodotos, we know that his Histories exemplifies a primitive form of the historical method.

Herodotos’s birthplace

We know very little about Herodotos’s life. He tells us very little about himself in his writings and, although his works are alluded to by several contemporary writers, these writers do not tell us about Herodotos the man. Later ancient writers have much to say about Herodotos’s life, but much of what they say about him is probably more speculation than actual history.

I will start out with the basic facts. We know that Herodotos was born in the Greek city of Halikarnassos in Asia Minor because he refers to himself as “Herodotos of Halikarnassos” in the introduction to his Histories, which reads as follows in Ancient Greek:

“Ἡροδότου Ἁλικαρνησσέος ἱστορίης ἀπόδεξις ἥδε, ὡς μήτε τὰ γενόμενα ἐξ ἀνθρώπων τῷ χρόνῳ ἐξίτηλα γένηται, μήτε ἔργα μεγάλα τε καὶ θωμαστά, τὰ μὲν Ἕλλησι τὰ δὲ βαρβάροισι ἀποδεχθέντα, ἀκλεᾶ γένηται, τά τε ἄλλα καὶ δι᾽ ἣν αἰτίην ἐπολέμησαν ἀλλήλοισι.”

Here is my own English translation of this passage:

“These are the researches of Herodotos of Halikarnassos, presented so that neither the doings of human beings nor the deeds great and marvelous, some produced by Hellenes and others by barbarians, will be forgotten by time and instead be kept alive, and especially the causes of why they went to war against each other.”

In addition to Herodotos himself, several other ancient writers also refer to Herodotos as having been born in Halikarnassos.

Halikarnassos was originally founded as a Dorian Greek colony, but inscriptions reveal that the Ionic dialect of the Greek language was spoken there during Herodotos’s lifetime. Herodotos’s Histories is written entirely in Ionic Greek, which is the dialect of the Greek language that Herodotos probably grew up speaking.

For Herodotos’s entire lifetime, Halikarnassos was part of the Persian satrapy of Karia, meaning Herodotos was actually born in the Achaemenid Empire. The Persians, however, did not directly rule Karia. Instead, it was directly ruled and administered by the regional Greek satrap. At the time Herodotos was born, the satrap of Karia was probably the Greek queen Artemisia I, whom Herodotos gives a favorable portrayal in his Histories.

The approximate date of Herodotos’s birth

It is generally thought Herodotos was probably born sometime in around the late 480s BC. In particular, the date that is usually given as the date of Herodotos’s birth is c. 484 BC. This date is based on several pieces of ancient evidence. As I will discuss in a moment, we know that Herodotos participated in the colonization of Thourioi, which occurred in around 444 or 443 BC. If Herodotos was about forty years old at the time, that would mean he was born in around the mid-to-late 480s BC.

The later Greek historian Dionysios of Halikarnassos (lived c. 60 – after c. 7 BC) states in his Life of Thoukydides that Herodotos was born shortly before the second Persian invasion of Greece, which occurred in 480 BC. The Roman historian Aulus Gellius (lived c. 125 – after c. 180 AD) cites the first-century AD Greek historian Pamphile of Epidauros as having written that Herodotos was about fifty-three years old when the Peloponnesian War began in 431 BC, which would mean he must have been born in around 484 BC or thereabouts. We cannot be sure exactly when he was born, but c. 484 BC is the best guess we are going to get.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of the port of the modern city of Bodrum, Turkey, which, in ancient times, was the Greek city of Halikarnassos, where Herodotos was born. The ancient theater and akropolis of Halikarnassos are visible in this photograph.

The Souda‘s account of Herodotos’s flight from Halikarnassos

The entry for Herodotos in the Souda, a tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia, claims that Herodotos was born into a prominent aristocratic family in Halikarnassos, but that he was forced to flee to the island of Samos on account of the tyrant Lygdamis II. Lygdamis II is known to have become the ruler of the Persian satrap of Karia in around 460 BC or thereabouts. Herodotos would have most likely been in around his mid-twenties when Lygdamis II ascended to power.

Another entry in the Souda claims that Lygdamis II executed the epic poet Panyasis, who, according to the Souda, was either Herodotos’s nephew or uncle. If Lygdamis II really executed one of Herodotos’s relatives, this would certainly have given Herodotos motive to flee the city.

As exciting as the Souda‘s account is, we must treat it with a great deal of skepticism. We have no way of knowing whether or not anything the Souda tells us about Herodotos is correct, since the Souda was written around 1,400 years after Herodotos’s death. Furthermore, the Souda frequently reports legends and apocryphal tales derived from late and unreliable sources. It is quite possible, even likely, that this whole story about Herodotos being related to the poet Panyasis and fleeing Halikarnassos to escape the rule of Lygdamis II is nothing more than a later legend.

Nonetheless, the Souda does rely on ancient sources that have now been lost, including some sources that probably date to not long after Herodotos’s lifetime. This means that we cannot entirely dismiss this account out of hand just because of the Souda‘s late date. As I said, though, we must treat it with skepticism.

ABOVE: Photograph of a Karian silver coin that was probably minted at Kaunos, near Halikarnassos, between c. 470 and c. 450 BC during the reign of Pisindelis. Herodotos would have been growing up in Halikarnassos at the time this coin was minted.

Herodotos’s travels

Leaving all that aside, we know that Herodotos definitely left Halikarnassos at some point and that he definitely spent a lot of his time wandering. In his Histories, he explicitly mentions having visited various places within the Greek world, including the island of Thasos (in 2.44), the shrine of Zeus at Dodona (in 2.55), the island of Zakynthos (in 4.195), the city of Thebes (in 5.57), and the region of Thessalia (in 5.57 as well). We have no good reason to doubt that he really visited these places.

Furthermore, although Herodotos does not explicitly describe himself as having lived on the island of Samos or in the city of Athens, it is widely thought among classicists that he probably did live for some period in both of these places. For one thing, Herodotos displays intimate knowledge of both of these places that seems to indicate he had visited them personally. In particular, he demonstrates an awareness of numerous specific Athenian local traditions that he could hardly have learned outside of Athens.

ABOVE: Modern-day photograph from Wikimedia Commons of the ruins of the temple of Zeus at Dodona. Herodotos mentions himself as having visited Dodona in Book Two of his Histories

Herodotos also portrays both Samos and Athens extremely favorably in his Histories, which some scholars have taken as evidence for an affinity towards these places. Other scholars, on the other hand, have objected that Herodotos may have portrayed the Athenians and Samians favorably for political reasons and not because he necessarily personally admired them.

Herodotos also claims to have visited various places from outside the Greek world, including Phoenicia (2.44), Palestine (2.106.1), Skythia (4.81.2), and, seemingly, Babylon (1.183.3, 1.93.4). Above all, though, Herodotos discusses his travels in Egypt in the greatest detail (2.112–113, 2.125, 2.143, etc.). Since ancient times, however, many people have doubted that Herodotos really visited all the places from outside the Greek world that he claims to have visited.

The fact that Herodotos’s description of Egypt closely lines up with recent archaeological discoveries, however, seems to indicate that he at least really did visit Egypt. For instance, in March 2019, archaeologists uncovered a type of ancient Egyptian cargo ship that was used on the Nile known as a bari. This kind of boat is described by Herodotos in his Histories 2.96, but, until this year, we had no concrete, archaeological evidence for the existence of this kind of boat. As it turns out, Herodotos’s description of the boat was exactly correct.

ABOVE: Photograph from the Smithsonian website of the shipwreck of an ancient Egyptian Nile cargo ship known as a bari. Herodotos describes this kind of ship in great detail in his Histories 2.96. The discovery of this boat, the first of its kind to be recovered by archaeologists, in March 2019 showed that Herodotos’s description of the ships was, in fact, completely correct.

Herodotos’s later years

We know that Herodotos eventually became a citizen of the colony of Thourioi in southern Italy. Thourioi was established as a Panhellenic colony in either 444 or 443 BC by Greeks from all different city-states and all different backgrounds. The laws of Thourioi are said to have been written by the Sophist Protagoras of Abdera (lived c. 490 – c. 420 BC), who was a moral relativist and one of the earliest recorded agnostics.

The philosopher Aristotle (lived 384–322 BC) refers to Herodotos as “Herodotos of Thourioi.” Herodotos is also described as having taken part in the colonization of Thourioi by the Lindos Chronicle (dated to c. 99 BC), by the Greek geographer Strabon of Amaseia (lived c. 64 BC – c. 24 AD), and by the Greek Middle Platonist philosopher and biographer Ploutarchos of Chaironeia (lived c. 46 – c. 120 AD). It is generally thought that Herodotos probably wrote most of the Histories while he was living in Thourioi.

ABOVE: Photograph of the obverse and reverse sides of silver stater from Thourioi, dating to the early fourth century BC, at least several decades after Herodotos’s death

The making of Herodotos’s Histories

Now that I have given a basic skeleton of what we know about Herodotos’s life, I shall delve into the question of how his Histories was published. It is highly unlikely that Herodotos’s Histories were “published” in the same way we might think of a book being published today. We do have mention from several ancient writers of certain “scrolls” being sold in the Athenian Agora and scrolls were probably sold in Agoras of other cities as well, but Herodotos’s Histories is an extremely long book.

Since texts in antiquity had to be copied entirely by hand, it is likely that the production of a single complete copy of Herodotos’s Histories would have taken at least several months, possibly more than a year, to produce. It would have taken far too long to produce a copy of Herodotos’s Histories for copies of it to have been sold in the Agora.

It is much more likely that Herodotos sustained himself primarily by working as an oral storyteller and lecturer. It has been traditionally thought among classicists that Herodotos’s Histories is actually based on a series of stories and lectures that Herodotos would perform aloud to wealthy patrons who were willing to pay him. This view is based partly on the fact that Herodotos’s Histories seems to contain a number of set “performance pieces” that are detachable from the main narrative and could have been performed individually.

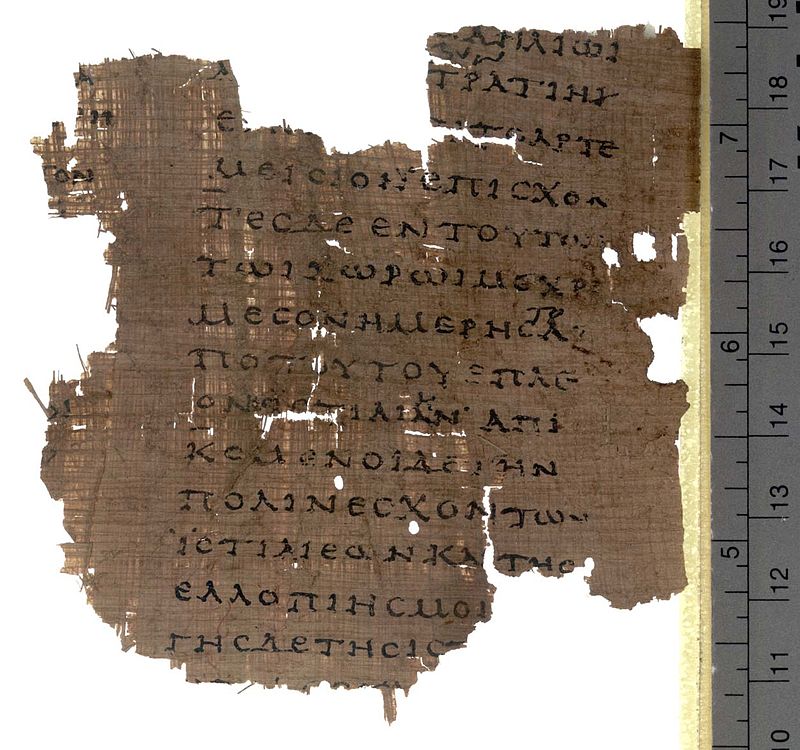

ABOVE: Photograph of Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 2099, a papyrus fragment discovered in the rubbish dump of the Greek city of Oxyrhynchos in Egypt, dating to the second century AD, bearing a portion of the text of Book Eight of Herodotos’s Histories. In ancient times, all texts were copied by hand.

There are also several later ancient writers, including the Syrian satirist Loukianos of Samosata (lived c. 125 – after c. 180 AD) and the Byzantine patriarch Photios I of Constantinople (lived c. 810 – 893 AD), who mention Herodotos having allegedly delivered public readings of passages from his Histories.

Similarly, the sixth-century AD Roman writer Marcellinus records a famous legend in his Life of Thoukydides that, supposedly, as a young child, the future historian Thoukydides (lived c. 460 – c. 400 BC) went with his father to attend a reading by Herodotos at Olympia of a portion of his Histories. Supposedly, Thoukydides wept upon hearing the words of the great historian and that was when he decided he wanted to be a historian as well.

This story is almost certainly apocryphal. It was almost certainly made up by people who wanted to imagine a meeting between the two great historians. Nonetheless, this anecdote and others like it do demonstrate that there was a tradition in antiquity claiming that Herodotos gave public readings from his Histories.

ABOVE: Photograph of a modern plaster cast of a Roman marble copy of a fourth-century BC Greek double-bust of Herodotos and Thoukydides, who were seen as the two greatest historians of ancient Greece

The dating of Herodotos’s Histories

Herodotos is generally thought to have composed his Histories in around the late 430s and early 420s BC. This is based on both internal and external evidence. The latest event chronologically that Herodotos mentions in his Histories is the Athenian capture of Spartan heralds in the second year of the Peloponnesian War, which he mentions in section 137 of Book Seven. This same event is also described by Thoukydides in Book Two of his Histories of the Peloponnesian War and can be dated precisely to 430 BC.

The earliest external references to Herodotos’s Histories are usually thought to be in the comedy The Acharnians, which was written by the Athenian comic playwright Aristophanes (lived c. 446 – c. 386 BC) and first performed at the Lenaia festival in Athens in 425 BC. If Aristophanes does indeed allude to Herodotos in The Acharnians, as most scholars believe he does, this means The Histories must have become publicly available at some point between 430 and 425 BC.

Several scholars, however, have argued that the passages in The Acharnians that are usually interpreted as references to Herodotos are not, in fact, references to him at all. These scholars argue that the first references to Herodotos actually occur in Aristophanes’s later play The Birds, which was performed in 414 BC at the City Dionysia.

ABOVE: Second-century AD Roman marble copy of a fourth-century BC Greek bust of Herodotos, identified as him by the inscription. Although this bust is definitely intended to represent Herodotos, the portrayal is probably fictional, given that even the Greek original on which this bust is though to have been based dates to the century after Herodotos’s death.

Criticism of Herodotos in antiquity

Herodotos’s Histories has always been a controversial work. Even in antiquity, there were many who criticized it for various reasons. Perhaps the oldest criticism of Herodotos is on account of the fact that he tells many fanciful and outlandish stories. The Athenian historian Thoukydides, a younger contemporary of Herodotos, obliquely alludes to Herodotos and other historians of his ilk in his Histories of the Peloponnesian War Book One, section twenty-two. Thoukydides writes, as translated by Richard Crawley:

“The absence of romance in my history will, I fear, detract somewhat from its interest; but if it be judged useful by those inquirers who desire an exact knowledge of the past as an aid to the interpretation of the future, which in the course of human things must resemble if it does not reflect it, I shall be content. In fine, I have written my work, not as an essay which is to win the applause of the moment, but as a possession for all time.”

The notion that Herodotos deliberately retold (or possible even fabricated) fanciful stories to win acclaim from his audience at the expense of truthfulness remained widespread throughout antiquity. We see this same criticism crop up again and again from different ancient writers.

For instance, in Book Two of the satirical novel A True Story, written by the Syrian satirist Loukianos of Samosata, who lived in the late second century AD, the protagonist and his crew visit an island in the Underworld, where they see Herodotos, Ktesias of Kyrene, and other ancient historians being tortured for the many “lies” they told. Here is the passage in question, as translated by A. M. Harmon:

“Forging ahead, we had passed out of the fragrant atmosphere when of a sudden a terrible odour greeted-us as of asphalt, sulphur, and pitch burning together, and a vile, insufferable stench as of roasting human flesh: the atmosphere was murky and foggy, and a pitchy dew distilled from it. Likewise we heard the noise of scourges and the wailing of many men… There was a single narrow way leading in, past all the rivers, and the warder set there was Timon of Athens. We got through, however, and with Nauplios for our conductor we saw many kings undergoing punishment, and many commoners too. Some of them we even recognized, and we saw Kinyras triced up as aforesaid in the smoke of a slow fire. The guides told the life of each, and the crimes for which they were being punished; and the severest punishment of all fell to those who told lies while in life and those who had written what was not true, among whom were Ktesias of Knidos, Herodotos and many more. On seeing them, I had good hopes for the future, for I have never told a lie that I know of. Well, I turned back to the ship quickly, for I could not endure the sight, said good-bye to Nauplios, and sailed away.”

Another common criticism of Herodotos in the ancient world was that he lacked patriotism, since he portrays non-Greek cultures—including even the Achaemenid Persians to a certain extent—in a remarkably favorable light and spends more time describing them and their customs than perhaps any other ancient Greek historian. Meanwhile, Herodotos portrays the Greeks who fought in the Persian Wars as fallible human beings, which later Greeks perceived as almost sacrilege.

Ploutarchos of Chaironeia famously wrote an essay entitled “On the Malice of Herodotos,” which is included in his Moralia. In this essay, Ploutarchos lambasts Herodotos for his favorable portrayal of non-Greek cultures, calling Herodotos a “φιλοβάρβαρος” (philobárbaros), which means “barbarian-lover” in Greek.

Among the other accusations levelled by Ploutarchos against Herodotos in his essay is that of undue favoritism towards the Athenians at the expense of other Greeks. Herodotos certainly does indeed portray the Athenians in a strongly positive light, but Ploutarchos’s assertion that he does this at the other Greeks’ expense is rather dubious.

Conclusion

Ultimately, despite all the criticisms Herodotos’s work has endured over the years, he remains a vital and irreplaceable source of historical information to this day. Herodotos tells us in his Histories 7.152 that he saw it as his duty to write everything he heard, regardless of whether or not he personally believed it. This attitude often led him to include many of the fanciful stories that he is so often criticized for, but it also led him to provide us with invaluable information about subjects that other historians would probably never have considered worth writing about.

Not just from a historical perspective, but also from a literary perspective, Herodotos’s work bears many merits. Thoukydides may be a more reliable historian than Herodotos most of the time, but Herodotos is certainly a far more entertaining storyteller. Thoukydides’s style is, frankly, dry and almost unreadable in places, but Herodotos’s style is much more lively and engaging.

Even in our modern age, we still need Herodotos.

As someone who (in English translation) has read Herodotos and tried to read Thoukydides, I suspect your comment about their styles are true in the original Greek.

As for Herodotos’ reliability, I like the way he reported a tale that a Pharaoh commissioned some Phoenicians to sail (& row) around Africa. He said he doubted the truth of the story because the Phoenicians reported they saw the sun to the *north* at noon as they rounded the southern end of Africa. So from the point he doubted but repeated anyway we know the story is true.

BTW spell check doesn’t like the way you write the names Herodotos & Thoukydides. I take it these non-standard spelling get the pronunciation closer to the original Greek.

After I posted my 1st comment I found your ‘Note on the Spellings of Foreign Names’.

Also I wonder if Herodotos influenced Henry the Navigator to organize trips south along the African coast.