Many people are familiar with the Greek and Roman deities from reading about classical mythology as children. One thing many people are not aware of, however, is that there are actually quite a few direct references to a number of different Greek deities in the Book of Acts in the New Testament, which describes the apostles visiting Greek cities and encountering opposition from supporters of traditional Greek religion. The deities mentioned in the Book of Acts by name are Zeus, Hermes, Artemis, and the Dioskouroi.

Paul and Barnabas mistaken for Zeus and Hermes

Acts 14:8–13 describes an incident that supposedly occurred during Paul and Barnabas’s visit to the Greek city of Lystra in the region of Lykaonia in Asia Minor. After Paul miraculously healed a lifelong cripple, the people of Lystra hailed him and Barnabas as the gods Hermes and Zeus respectively. Here is a translation of the passage from the NRSV:

“In Lystra there was a man sitting who could not use his feet and had never walked, for he had been crippled from birth. He listened to Paul as he was speaking. And Paul, looking at him intently and seeing that he had faith to be healed, said in a loud voice, “Stand upright on your feet.” And the man sprang up and began to walk. When the crowds saw what Paul had done, they shouted in the Lycaonian language, “The gods have come down to us in human form!” Barnabas they called Zeus, and Paul they called Hermes, because he was the chief speaker. The priest of Zeus, whose temple was just outside the city, brought oxen and garlands to the gates; he and the crowds wanted to offer sacrifice.”

ABOVE: The Sacrifice at Lystra, painted in 1515 by the Italian Renaissance painter Raffaelo Sanzio da Urbino (“Raphael”)

The ancient Greeks from the very earliest times believed that gods sometimes came to earth in disguise in order to observe human behavior and that a person could never take it for granted that the person they were speaking to was really mortal. In the Odyssey Book 17, lines 485-487, one of the suitors declares, as translated by Robert Fitzgerald:

“You know they go in foreign guise, the gods do,

looking like strangers, turning up

in towns and settlements to keep an eye

on manners, good or bad.”

Early Christians maintained a very similar belief to this. Early Christians, of course, did not believe that deities came to visit mortals in disguise, but they did believe that angels sometimes did this. Hebrews 13:2 warns: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by doing that some have entertained angels without knowing it.”

Inscriptions from Lystra have demonstrated that Zeus and Hermes were worshipped there together. This account of Paul and Barnabas being mistaken for Zeus and Hermes also relates to the ancient legend of Baucis and Philemon, set in the region of Tyana, which neighbored Lykaonia. This story is told by the Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso (lived 43 BC – c. 17/18 AD) in Book VIII, lines 611-678, of his long poem Metamorphoses, a collection of myths and fables from around the Mediterranean written in around 8 AD.

In Ovid’s retelling of the story, the gods Jupiter and Mercury (the Roman equivalents of the Greek gods Zeus and Hermes respectively) visit a town in the region of Tyana in Asia Minor, disguised as weary travelers. They knock on all the doors asking for a place to stay the night, but every single household turns them away. Finally, they come upon a rustic cottage on the edge of town where there lives a poor, elderly couple named Baucis and Philemon. Baucis and Philemon led the two gods into their home and prepared them a meal of bread and wine.

As Baucis pours the wine from the pitcher, however, she discovers that it always remains full, no matter how much she pours out. Suddenly, the couple realize that their guests are deities, so they throw their hands up and plead them for forgiveness for the simple meal. Philemon thinks about fetching the family’s only goose to kill and serve to the gods, but Jupiter preemptively tells him not to.

Instead, he commands them to leave the city and flee to the nearest mountain at once, warning them not to turn back until they reach the summit. Baucis and Philemon do as Jupiter commanded and, once they reach the summit of the mountain, they look back to see that the rest of the city has been completely destroyed by a flood and that their tiny cottage has been transformed into an enormous, ornate temple to the gods, which Jupiter and Hermes entrust them as the caretakers of.

ABOVE: Jupiter and Mercury in the House of Baucis and Philemon, painted c. 1620-1625 by the Dutch Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens, or by one of his students

“Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!”

Acts 19:23–34 describes riot against Paul’s teaching led by a silversmith named Demetrius in the city of Ephesus, where Artemis was the patron goddess:

“About that time no little disturbance broke out concerning the Way. A man named Demetrius, a silversmith who made silver shrines of Artemis, brought no little business to the artisans. These he gathered together, with the workers of the same trade, and said, “Men, you know that we get our wealth from this business. You also see and hear that not only in Ephesus but in almost the whole of Asia this Paul has persuaded and drawn away a considerable number of people by saying that gods made with hands are not gods. And there is danger not only that this trade of ours may come into disrepute but also that the temple of the great goddess Artemis will be scorned, and she will be deprived of her majesty that brought all Asia and the world to worship her.”

“When they heard this, they were enraged and shouted, “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!” The city was filled with the confusion; and people rushed together to the theater, dragging with them Gaius and Aristarchus, Macedonians who were Paul’s travel companions. Paul wished to go into the crowd, but the disciples would not let him; even some officials of the province of Asia, who were friendly to him, sent him a message urging him not to venture into the theater. Meanwhile, some were shouting one thing, some another; for the assembly was in confusion, and most of them did not know why they had come together. Some of the crowd gave instructions to Alexander, whom the Jews had pushed forward. And Alexander motioned for silence and tried to make a defense before the people. But when they recognized that he was a Jew, for about two hours all of them shouted in unison, “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!”

Here is a photograph of a first-century AD cult statue of Artemis as she was worshipped in Ephesus from the Ephesus Archaeological Museum:

Here is another marble statue of Artemis of Ephesus from the Ephesus Archaeological Museum, also dated to the late first century AD:

The Dioskouroi as the figurehead on Paul’s ship

In Acts 28:11, there is a brief blink-and-you’ll-miss-it reference to the Dioskouroi, the twin gods Kastor and Polydeukes. Kastor and Polydeukes were sons of Zeus who were believed to aid sailors lost at sea. In this passage, the figurehead on the ship Paul was put on when he was being sent to Rome is described as having been carved to look like the Dioskouroi:

“Three months later we set sail on a ship that had wintered at the island, an Alexandrian ship with the Twin Brothers as its figurehead.”

Here are two third-century AD Roman statuettes depicting Kastor and Polydeukes, the Dioskouroi. The Phrygian caps they are wearing and the horses they have with them are characteristic of their iconography. The figurehead on the ship Paul is described as being transported on in this passage would have probably included these features in some form or another:

Possible indirect allusions outside of Acts

The Book of Acts is the only book in the New Testament that specifically mentions Greek deities by name, but other books in the New Testament frequently seem to allude to them indirectly, particularly the Gospel of John. For instance, in John 4:1-26, Jesus is portrayed as having a discussion with a Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well in the Samaritan city of Sychar. In John 4:13-14, Jesus tells her, “Everyone who drinks of this water will be thirsty again, but those who drink of the water that I will give them will never be thirsty. The water that I will give will become in them a spring of water gushing up to eternal life.”

The cult of the god Mithras, which was just becoming popular in the Roman Empire in the late first and early second centuries AD, around the same time when the Gospel of John was written, is known to have used water as an important aspect of its rituals. Some scholars have therefore interpreted the Gospel of John’s “Water of Life Discourse” as potentially a polemic against the Mithraic cult. When the author of the Gospel of John presents Jesus as saying that whoever drinks “this water,” as in earthly water, will “be thirsty again,” he may be deliberately trying to criticize the Mithraic cult’s use of holy water. The gospel-writer then introduces a new kind of water symbolism: water as a symbol of eternal life through Jesus Christ.

ABOVE: Jesus and the Samaritan Woman at the Well, painted by the Danish Academic painter Carl Heinrich Bloch (lived 1834 – 1890)

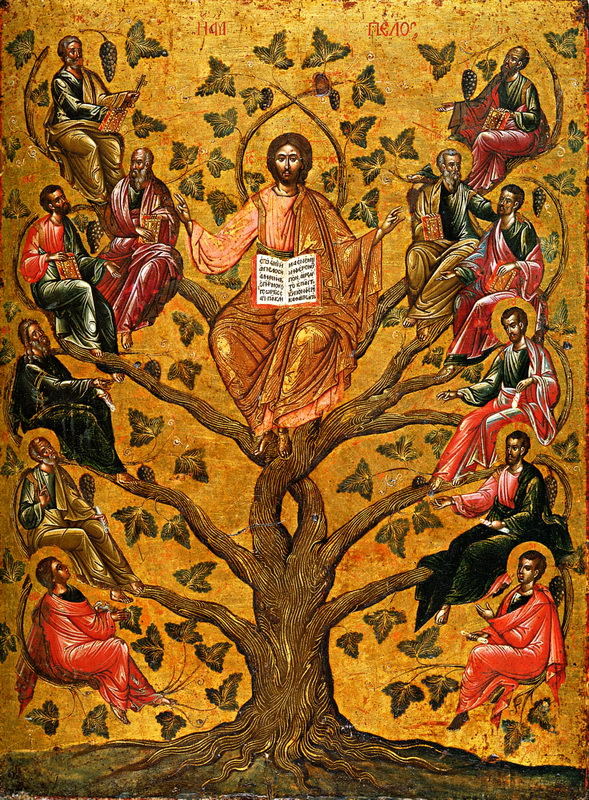

A less contentious example of a possible indirect allusion to a Greek deity in the Gospel of John occurs in John 15:1–17, in which Jesus tells an allegory in which he calls himself “the true vine.” Many scholars have interpreted this discourse as a subtle polemic against the cult of the Greek god Dionysos, who was worshipped in association with wine, drinking, grapes, and vines. In essence, in this passage, the author of the Gospel of John seems to be deliberately presenting Jesus in direct opposition to Dionysos; he says that Jesus is the true vine, which clearly would have implied that Dionysos was not the true vine.

ABOVE: Sixteenth-century Greek icon of Jesus as the True Vine

There may also be an oblique reference to Zeus in Revelation 2:13, in John of Patmos’s epistle to the church of Pergamon:

“I know where you are living, where Satan’s throne is. Yet you are holding fast to my name, and you did not deny your faith in me even in the days of Antipas my witness, my faithful one, who was killed among you, where Satan lives.”

Many scholars believe that the reference to “Satan’s throne” is alluding to the Pergamon Altar, a massive monumental construction built by King Eumenes III in the early second century BC and dedicated to Zeus and the Twelve Olympians. Here is a photograph of the modern reconstruction of the original Pergamon Altar in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, Germany:

Great summary!

Jesus’ Water teaching is ‘Jewish” not pagan. It had to do with the Water Festival during the Holy Day rituals at the temple.

Jesus’ Vine teaching was a metaphor from their annual agrarian customs, not anti-pagan polemic.

Cheers!

Perhaps what you say is correct. On the other hand, it is quite possible that the sayings about the “Water of Life” and the “True Vine” draw on both pagan and Jewish imagery.

Also, Acts 16:16

…and Acts 28:4