NOTE: I originally published this article on March 10, 2018, at which time I was still a senior in high school. Since then, this article has come under extremely heavy criticism. I could probably write this article better if I were writing it today, but I will leave this article as it is as a record of what I originally wrote.

No other figure has attracted nearly as much controversy as Jesus of Nazareth… but was he a historical figure? Well, people on the internet seem to say otherwise: these self-appointed debunkers (who are almost exclusively historically illiterate bloggers with no background in ancient history, or any history for that matter) have taken it upon themselves to demonstrate that Jesus is just a fictional character invented out of whole cloth by early Christians. Virtually all professional scholars who have studied the ancient world universally agree that Jesus of Nazareth was a real, historical Jewish teacher who lived in the first century AD and was crucified under the orders of Pontius Pilate. Here is an extremely abbreviated explanation of why they have come to that conclusion:

Evidence for the historical existence of Jesus from the writings of Paul

The oldest writings we have pertaining to Christianity are the authentic epistles of the apostle Paul, of which there are at least eight. (n.b. Of the thirteen epistles attributed to Paul included in the New Testament, one of them – Hebrews – never actually claims to have been written by Paul and an additional five – 2 Thessalonians, Ephesians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus – are now known to have been at a much later date by someone else in Paul’s name. Scholarly consensus on the authenticity of Colossians is divided roughly evenly.)

The earliest of Paul’s epistles is probably Galatians, which may have been written in 49 AD, only around sixteen years after Jesus’s death. Paul does not say a whole lot about Jesus and he candidly admits that he never actually met Jesus in the flesh while he was still alive on earth, but he does tell us that he knew Jesus’s “brother” James, as well as his closest disciple Peter.

ABOVE: Paul Writing His Epistles (seventeenth century) by Valentin de Bologne. This painting is actually historically inaccurate, because most historians agree that Paul probably dictated his epistles to a scribe rather than writing them himself, apparently because of poor eyesight or bad handwriting, as indicated by passages such as Galatians 6:11 and Romans 16:22.

The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches, as well as a number of Protestant denominations, have traditionally taught that the “brothers” of Jesus mentioned in the New Testament are actually either his cousins or Joseph’s children from a previous marriage, but this idea is almost certainly erroneous, since they are always consistently described as Jesus’s brothers, using the Greek word ἀδελφοί (adelphoí), which literally means “from the same womb.”

In any case, the fact that Paul knew Jesus’s own brother is the strongest (though certainly not the only) piece of evidence to support the fact that Jesus was a historical figure. As historian of early Christianity Bart Ehrman (an agnostic) remarks:

And so Jesus’ brothers were his actual brothers. Paul knows one of these brothers personally. It is hard to get much closer to the historical Jesus than that. If Jesus never lived, you would think that his brother would know about it.

Supporters of the so-called “Christ Myth theory” (i.e. “Mythicists”) often claim that the reason why Paul says so little about Jesus is because the “Jesus myth” had not yet fully developed. This is the result of a complete misunderstanding of Paul’s purpose in writing. Paul does not talk much about Jesus because his audiences are all baptized Christians who he assumes already know the full story of the gospel. Since Paul assumes that his audience already knows about Jesus, he has no reason to describe in detail any of the stories from the gospel because that would… well, be pointless. It was only later that Christians became concerned with the idea of trying to create a written record of Jesus’s life and teachings.

Although Mythicists often claim that Paul only speaks of an incorporeal “spiritual” Jesus, they have repeatedly failed to adequately address the dozens of places in Paul’s letters where he very clearly speaks of Jesus as a recent, historical figure and even refers to sayings and events that would later be recorded in the Synoptic Gospels, including in, among other places, Galatians 4:4, Romans 1:3-4 and 15:8; 1 Corinthians 2:2, 7:10, 9:14, 11:22-24, and 15:3-4. (And this is not even including the famous passage of doubtful authenticity in 1 Thessalonians 2:14-16 in which Paul apparently claims that “the Jews” killed Jesus.) One common argument employed by Mythicists is to simply explain these occurrences away as “later interpolations,” without offering any valid evidence to support such a conclusion other than the fact that it would be convenient for their hypothesis.

Another common argument is to claim that Paul is not talking about an earthly, human Jesus, but rather a spiritual Jesus who was crucified in a spiritual realm, usually by demons. Where is the evidence for early Christian belief in this supposed “spiritual realm”? There is none; its proponents have just made it up.

(There is a text known as The Ascension of Isaiah that some Mythicists have claimed supports this view of Christ being crucified in a heavenly realm, but it does not; the text describes Isaiah in heaven seeing a vision of Jesus’s crucifixion taking place on earth, not in heaven. Furthermore, The Ascension of Isaiah was probably written in several stages by different authors over the course of many years, and the part at the end about Jesus, which is almost certainly the latest portion of the text, may have been written as late as the late third century AD, making it hardly of relevance for what the earliest Christians thought about Jesus.)

Evidence for the historical existence of Jesus from the gospels

Further evidence to support Jesus’s historicity comes from the fact that the gospels contain details that can only be explained if Jesus was a historical figure. Before I discuss those details, however, I should first note that we do not know who wrote the gospels; they are, in fact, completely anonymous.

The names of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John that we know them by today were assigned to them in the early second century in a more-or-less arbitrary manner. This, however, does not in any way devalue the importance of the gospels as historical sources. The reason why they are anonymous is because they were originally intended to be used by members of the author’s own, specific community and no one really cared that much who wrote them until much later.

Embarrassing, or mundane facts about Jesus’s life are mentioned in Mark, the earliest gospel, which was written in around 70 AD, only forty years or so after Jesus’s death, but are rationalized or contradicted in the later gospels in overtly obvious attempts to overwrite the earlier account. For instance, the Gospel of Mark clearly states that Jesus came from Nazareth.

Nazareth, however, was an extremely tiny, obscure town in the middle of nowhere with a population of probably less than 200 people. It was far from dignified enough to be the birthplace of the Savior of the World. Furthermore, most Jews in the first century believed that the Messiah was supposed to come from Bethlehem, just like King David. The author of the Gospel of Mark never mentions anything about Bethlehem in his gospel.

We know that Jesus’s origins were extremely problematic to later Christians because the Gospel of John repeatedly references this fact. In John 1:42-46, when Philip tells Nathan that Jesus comes from Nazareth, his immediate response is “Nazareth! Can anything good come from there?” Later, in John 7:42, a group of disbelieving Jews remark: “Does not Scripture say that the Messiah will come from David’s descendants and from Bethlehem, the town where David lived?” (This, of course, implies that Jesus did not come from Bethlehem, or at least that no one thought he did.)

So devastating was the problem of Jesus’s origins that the Gospels of Matthew and Luke both try to invent extremely convoluted and, especially in the case of Luke, historically impossible, explanations for how Jesus could have been secretly born in Bethlehem, even though it was a well-known fact that he had grown up in Nazareth.

The point here is that if Christians had invented Jesus from whole cloth, they would never have said that he came from Nazareth; they would have said that he came from Bethlehem from the very start and that that was where he grew up. The only reason why they did not do this was because Jesus was a real person and everyone knew he had come from Nazareth.

Here is another interesting problem: In Mark 6:3, members of a baffled crowd in Nazareth say regarding Jesus: “Is not this the carpenter [τέκτων], the son of Mary, the brother of James, and Joses, and of Juda, and Simon? and are not his sisters here with us?” Matthew 13:55, however, shifts the word “carpenter” to refer to Jesus’s father instead: “Is not this the carpenter’s son? is not his mother called Mary? and his brethren, James, and Joses, and Simon, and Judas?”

It is a subtle change and it is historically probable, even likely, that, since trades in antiquity were usually passed from father to son, if Jesus was a carpenter, then his father was probably a carpenter as well, but the fact that the author of the Gospel of Matthew changes Mark’s wording here indicates that early Christians were troubled by the fact that their savior had been a practitioner of such a lowly trade as carpentry. If early Christians had invented Jesus, they would have never said that he was a carpenter to begin with, so we may therefore deem Jesus’s occupation as a carpenter as yet another fact about his life that is effectively historically certain.

Likewise, the Gospel of Mark records Jesus as being baptized by John the Baptist. This was embarrassing to early Christians for two reasons: Firstly, baptism was for the remission of sins and, if Jesus was baptized, that directly implies that he had sins that needed to be forgiven. Secondly, if Jesus was baptized by John, that implies that John was his spiritual superior. The reason Mark tells this story can therefore only be because it really happened and everyone knew it, so if he did not tell it, they would distrust him. The later Gospel of Matthew tries to explain away the baptism as a necessary fulfillment of prophecy, something which Mark noticeably does not do.

ABOVE: The Baptism of Christ (1895) by Almeida Júnior. The baptism of Jesus by John is a story that was embarrassing to early Christians and is therefore certainly historical since it is something that no Christian would have made up.

An even more embarrassing fact for early Christians was Jesus’s crucifixion. It is impossible to explain to a modern audience just how humiliating a Roman crucifixion was; it was the absolute most hideous, most shocking, most degrading way a person could possible die. It was so humiliating that the punishment was reserved only for slaves and the worst of criminals.

Jesus’s crucifixion was the greatest factor impeding the spread of the new religion. Paul repeatedly references how repulsive people found the notion of a crucified savior. For instance, in 1 Corinthians 1:23, he states, “but we preach Christ crucified: a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles.” If Christians had invented Jesus, they would never have considered the idea of telling people that he had been crucified. The only reasonable explanation for why they would ever claim such a thing is if it had really happened and everyone else knew it.

Furthermore, Jesus does not even remotely match the idea that most Jews in the first century would have had about what the Messiah would be like. They believed that the Messiah was supposed to be a great warrior-king who would drive out the Romans and restore the Kingdom of David. Instead, Jesus was a pacifist preacher who, rather than driving out the Romans like he was supposed to, ended up being crucified by the Romans instead.

No one in the first century was expecting the Messiah to suffer and, although there are plenty of Old Testament passages that Christians have retrospectively interpreted as referring to a suffering Messiah, this interpretation did not exist during in Judaea during the time when Jesus was alive. In fact, to most Jews, Jesus’s crucifixion would have been seen as proof that he was a fraud and a charlatan, since Deuteronomy 21:23 states, “he that is hanged is accursed of God.”

ABOVE: Christ at the Cross (1870) by Carl Bloch. Crucifixion was so repulsive and disturbing to ancient peoples that no one would have ever claimed that their Messiah had been crucified unless it had really happened and everyone else knew it.

Finally, there are also distinct cultural features within the gospels that only make sense in the context of early first-century Aramaic Judaism, but not late first-century Hellenistic Christianity. Jesus’s teachings as they are recorded in the Synoptic Gospels are overwhelmingly and quite obviously Jewish in character.

To give just one of many examples, Jesus teaches quite extensively about the Law of Moses, something which was important to his original Jewish audience, but not so much to his later Gentile followers. The Synoptic Gospels also reference distinct first-century Jewish customs, such as the giving of peah in Mark 2:23, that a Gentile audience would probably not be familiar with. The Gospel of Mark and, to a lesser extent, the Gospel of Matthew, quote Jesus saying things in Aramaic, the language of Jesus and his earliest followers, even though their Hellenistic Greek-speaking audiences would almost certainly not understand a word of this language.

Additionally, Greek phrases used in the Synoptic Gospels such as ὁ υἱὸς τοὺ ἀνθρώπου (“the Son of Man”) are clearly translations of phrases from Aramaic. (The conventional Aramaic phrase used to refer to a human being literally means “son of man.”) All these features of the gospels are best explained by the existence of a strong oral tradition going all the way back to Jesus himself.

Certain passages indicate that the Gospel of Mark may even rely on textual sources written in Aramaic, such as when he apparently mistranslates the Aramaic word meaning “to be moved with passion” as the Greek word meaning “to be angry” due to the double meaning of the Aramaic phrase, or when he says that Jesus’s followers “began to make a path” instead of “follow a path” due to the visual similarity of the two Aramaic words on paper.

Legendary details in the gospels

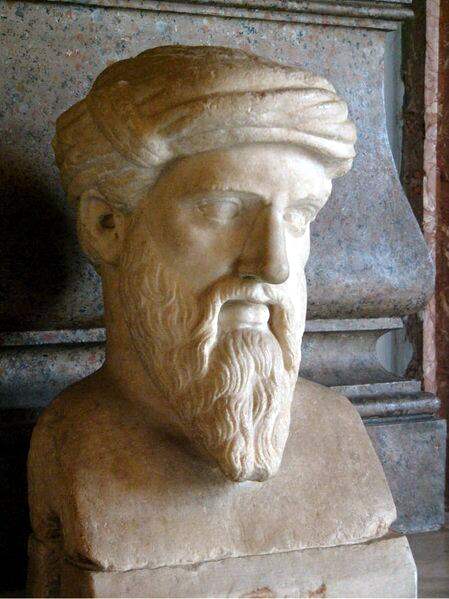

Some Mythicists frequently insist that, because the gospels contain obviously legendary material, they must therefore be totally disregarded as historical documents. This is not a reasonable conclusion; of course there are plenty of unreliable legends about Jesus, but there are similar legends about nearly every historical figure from antiquity. Take, for instance, the great ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras of Samos (lived c. 570 – c. 495 BC).

By the time the first full biographies of his life were written down, all sorts of bizarre legends of a Chuck Norris variety were already established. If these legends are to be believed, Pythagoras was the son of the god Apollon; he had a golden thigh; when he crossed the river Cascas, it greeted him by name; the priest of Apollon gave him a magic arrow, which he used to fly around; when he was bitten by a venomous snake, he bit it back and it died.

None of these legends in any way prove that Pythagoras himself was not a real person. In fact, we know he was a real person because he is mentioned shortly after his death by several of his near-contemporaries, including Xenophanes of Kolophon, Alkmaion of Kroton, and Herakleitos of Ephesos. These writers are to Pythagoras as Paul is to Jesus and Xenophanes and Alkmaion, at least, may have known either Pythagoras himself or other members of his circle, in the same way that Paul knew several of Jesus’s earthly followers.

ABOVE: Bust of Pythagoras from the Capitoline Museums, Rome, showing him as he was imagined by later Greeks. (No one knows what the historical Pythagoras really looked like.)

Do not mistake me; I am not trying to argue that Jesus was really born of a virgin, that he really performed miracles, that he really walked on water, or even that he really rose from the dead. None of those things can be substantiated historically. There is a massive difference between stating that a person existed as a historical figure and claiming that that same person performed supernatural feats.

Hardly anyone today believes the apocryphal legend told by the Church Father Origen of Alexandria (lived c. 184 – c. 253 AD) that the Greek philosopher Plato (lived c. 427 – c. 347 BC) was born of a virgin, yet no one doubts—or has any legitimate reason to doubt—the fact that Plato was a real person. The same is the case with Jesus; merely saying that he existed should not be conflated with making more extreme claims regarding his abilities and identity.

The supposed missing “contemporary” evidence

A claim ubiquitous among Mythicists is the idea that Jesus is never mentioned in any contemporary sources and that this somehow “proves” that he never existed. This notion is only partly true. Whether there are any “contemporary” sources depends on what you consider “contemporary.” Technically, Paul is a contemporary of Jesus, since he lived during Jesus’s lifetime, but what Mythicists are really looking for are historical documents written by non-Christian historians dating to the time while Jesus himself was still alive. There are absolutely none.

The problem, however, is that the Mythicists are operating on two fundamentally flawed assumptions. The first assumption is that we have a vast amount of meticulous historical records made by the Romans, who Mythicists apparently assume kept perfect track of everything whatsoever that happened within their empire. This idea is totally wrong. Our sources for all of history up until around one thousand years ago are extremely scanty. It would be possible to read the entire surviving corpus of Greek and Roman writings within about eight months if you were to do it as a full-time job.

The reason why the sources are so scanty is not necessarily because the Romans were poor record-keepers, but rather because the overwhelming majority of ancient records simply have not survived to the present day. This was not the result of some vast conspiracy by Christians or some other group to destroy classical documents, but rather the natural and inevitable result of the passage of time.

Prior to the invention of the printing press, all documents had to be copied entirely by hand, which was extremely laborious and time-consuming. It could take months or even years for a single scribe or even a team of scribes to copy out an entire book, depending on how long the book in question happened to be.

Furthermore, the only available materials to write on were papyrus and parchment. Papyrus, the cheaper and more commonly used of the two, is extremely brittle and fragile, much more so than modern paper. Under normal conditions of fluctuating temperatures and continued use, a papyrus scroll can only last for about fifty years before it wears out and has to be recopied.

The process of hiring a scribe to copy a manuscript was also extremely expensive. The only way a document could be preserved was if roughly every fifty years some rich person decided that a text was so important that he or she wanted to pay a huge amount of money to have it copied. This went on, not just for a few centuries, but for over two millennia until the printing press was finally invented in the 1430s. We are unbelievably fortunate that anything at all has survived.

The second faulty assumption the Mythicists are making is that the Romans would have taken interest in Jesus. The first problem with this assumption is that Jesus’s ministry was, until the very end, almost exclusively confined to Galilee, which was, from the Romans’ perspective, a tiny, remote backwater client state of little use or significance. The Romans could hardly have had less interest in what went on in Galilee; unlike Gaul or Egypt, it was of little economic interest and, unlike Greece, it was of little cultural interest.

Technically, the Romans did not even directly rule Galilee, since it was actually ruled by their client king Herod Antipas, the son of Herod the Great. The second problem is who Jesus was; the gospels portray him as an itinerant religious preacher who taught mainly in small fishing towns and villages like Capernaum, Bethsaida, and Magdala along the coast of the Sea of Galilee.

There is no reason to believe that this variety of teacher would have attracted any serious attention from contemporary Greek or Roman writers, especially since were know from the writings of the Jewish historian Josephus (lived 37 – c. 100 AD) and from the Babylonian Talmud that teachers of this variety were a dime-a-dozen during this time period. Quite simply, it is highly improbable that any Roman historian from Jesus’s lifetime would have cared about him in the slightest.

The only people in the first century who wrote extensively about Judaea and Galilee at all were not Greeks or Romans, but rather Jews themselves. The writings of only two major Jewish authors from the first century have survived. The earlier of these writers is the Jewish Middle Platonist philosopher Philo of Alexandria (lived c. 20 BC – c. 50 AD). Philo was a contemporary of Jesus and he does not mention him, but this is hardly surprising for several reasons.

Philo lived almost his entire life in the city of Alexandria in Egypt and there is no evidence that he ever visited Galilee. Although Philo sometimes references major political events taking place in Judaea, such as the numerous controversies surrounding the prefect Pontius Pilate (the same one the gospels record sentencing Jesus be crucified), he demonstrates virtually no interest in writing about obscure religious teachers.

In fact, the only non-Christian writer from the entire first century AD that anyone could have reasonably expected to mention Jesus is the Jewish historian Josephus, who was the military governor of Galilee during the Jewish revolt in the late 60s AD and who writes extensively about dozens of obscure religious leaders from the first century, many of whom are remarkably similar to Jesus. The problem for the Mythicists, of course, is that he does mention Jesus—twice, in fact, in his monumental history of Judaea The Antiquities of the Jews, written in around 94 AD, around sixty years after Jesus’s death.

ABOVE: Early nineteenth-century engraving showing the artist’s imagining of what Josephus might have looked like (No one knows what the historical Josephus actually looked like either.)

The first reference by Josephus is found in Antiquities XVIII.3.3. Most scholars agree that this passage has probably been partially altered by later Christian copyist, but that the majority of the passage is authentic:

Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man; for he was a doer of wonderful works, a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews and many of the Gentiles. He was [the] Christ. And when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him; for he appeared to them alive again the third day; as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him. And the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day.

Most historians agree that the core of the passage is authentic because it contains phrases that are characteristic of Josephus, but which a later Christian forger would be extremely unlikely to use, especially in describing Jesus or Christians. For instance, Josephus calls Christians a “tribe,” a word which no Christian writer is ever attested as using in this context. Josephus calls Jesus “a wise man,” a phrase that a Christian writer would be extremely unlikely to use while describing his divine Savior.

The phrase “Now there was about this time,” which occurs at the beginning of the passage, is a characteristic lead-in used by Josephus in dozens of other places. Furthermore, the Testimonium Flavianum occurs in some form in all of the extant manuscripts of Antiquities of the Jews, except for one late medieval Hebrew translation, which seems to omit the passage intentionally.

Further support for the authenticity of the core of the passage comes from the fact that several Arabic manuscripts have survived which appear to preserve Josephus’s original wording before it passage was tampered with by Christian scribes. The Arabic manuscripts omit the phrase “if it is lawful to call him a man” and, in the Arabic manuscripts, Josephus does not say that Jesus was the Christ, but rather that he was called the Christ.

Nonetheless, a few legitimate historians have argued that the passage is entirely a later Christian insertion. The main arguments against the authenticity of the entire passage are that it occurs in the middle of a narrative about calamities that befell the Jews during the time of Jesus’s ministry, which makes the passage’s placement highly awkward, and that the passage is never quoted by any Christian writers until the historian Eusebius, who lived in the early fourth century.

Neither of these are particularly strong arguments. While the passage’s placement is rather unusual, Josephus frequently breaks up other narratives with tangential anecdotes, a tendency which can be explained by the fact that ancient historians did not use footnotes. The fact that no Christian writer quotes the passage means very little, since there is no indication that early Christians would have had reason to quote it, since none of the enemies of Christianity until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries ever disputed the subject of Jesus’s historical existence (more on this fact below).

In any case, however, there is another passage mentioning Jesus in Antiquities XX.9.1, which all historians – even the ones who have contested the Testimonium Flavianum – universally agree is authentic. This passage is known as the “James reference” because the passage primarily concerns the death of Jesus’s brother James (the same one I mentioned earlier while I was talking about Paul):

And now Caesar, upon hearing the death of Festus, sent Albinus into Judea, as procurator. But the king deprived Joseph of the high priesthood, and bestowed the succession to that dignity on the son of Ananus, who was also himself called Ananus. Now the report goes that this eldest Ananus proved a most fortunate man; for he had five sons who had all performed the office of a high priest to God, and who had himself enjoyed that dignity a long time formerly, which had never happened to any other of our high priests. But this younger Ananus, who, as we have told you already, took the high priesthood, was a bold man in his temper, and very insolent; he was also of the sect of the Sadducees, who are very rigid in judging offenders, above all the rest of the Jews, as we have already observed; when, therefore, Ananus was of this disposition, he thought he had now a proper opportunity [to exercise his authority]. Festus was now dead, and Albinus was but upon the road; so he assembled the sanhedrim of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James, and some others, [or, some of his companions]; and when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned: but as for those who seemed the most equitable of the citizens, and such as were the most uneasy at the breach of the laws, they disliked what was done; they also sent to the king [Agrippa], desiring him to send to Ananus that he should act so no more, for that what he had already done was not to be justified; nay, some of them went also to meet Albinus, as he was upon his journey from Alexandria, and informed him that it was not lawful for Ananus to assemble a sanhedrim without his consent. Whereupon Albinus complied with what they said, and wrote in anger to Ananus, and threatened that he would bring him to punishment for what he had done; on which king Agrippa took the high priesthood from him, when he had ruled but three months, and made Jesus, the son of Damneus, high priest.

The James Reference is not only a clear and certain mention of Jesus, but it also strongly indicates in favor of the authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum, since the terse manner in which Josephus happens to just casually mention Jesus implies that he has already been described to the reader in much greater depth.

Blogger and atheist activist Richard Carrier (who, to his credit, does have a PhD in ancient history) has claimed that the words “who was called Christ” are a later Christian insertion and that the name “Jesus” is really referring to the “Jesus, son of Damneus” mentioned at the end of the paragraph.

This hardly makes any sense, though, because “Jesus” was an extremely common name in Judaea during the first century. (In fact, it is estimated that roughly one fifth of all males living in Judaea at the time were named “Jesus.”) As such, it would have been recklessly ambiguous for Josephus to just mention someone named “Jesus” without any further explanation. If Josephus were really referring to “Jesus, son of Damneus,” the passage would have originally said “Jesus, son of Damneus,” not just “Jesus.”

Once again, it is important to emphasize that, even if Josephus had not mentioned Jesus, that still would not in any way indicate that Jesus was imaginary. We already have overwhelming evidence in favor of Jesus’s historicity from Paul and the Synoptic gospels, which makes Josephus’s testimony little more than icing on the cake. In addition to Josephus, there are also several slightly later references to Jesus by various Roman and Greek writers.

The Roman governor Pliny the Younger (lived 61 – c. 113 AD) briefly mentions Jesus in a letter to the Emperor Trajan, written around 112 AD, asking for counsel on how to deal of Christians. The Roman historian Tacitus (lived c. 56 – c. 120 AD) also mentions Jesus in his Annals Book 15, Chapter 44, which was probably written around 116 AD or thereabouts, in which he provides a brief thumbnail sketch of Jesus’s life in the context of a description of the Emperor Nero’s persecution of Christians after the Great Fire of 64 AD. Tacitus and Pliny’s accounts are both interesting, but, since they both date to the second century, by which time Mythicists claim that the mythical Christ had already been invented, they are hardly of much use for establishing Jesus’s historicity.

The missing evidence of a Mythicist Christianity

Another devastating piece of evidence against the Christ Myth theory is the fact that there is absolutely no evidence that anyone even questioned the historical existence of Jesus until the eighteenth century. In order for the Mythicist hypothesis to hold water, we would need evidence that there were at least some early Christians who believed that Jesus was a solely spiritual being who had never lived on earth.

The problem is that all the early Christian sources unanimously agree that Jesus was a recent historical figure. The closest thing we ever encounter to a truly Mythicist Christianity is the Docetist heresy of the second century AD. The Docetists maintained that Jesus was not really human and that he was really a spirit, but that he appeared (δοκεῖν; dokeĩn) to be human. They taught that Jesus really came to earth and that he really led an earthly ministry, but they claimed that he did so as a spirit, not as a man.

Even more convincing is the fact that not only Christians, but even the most vicious opponents of Christianity accepted Jesus as a historical figure. If there had ever been even the slightest reason to doubt Jesus’s historical existence, Christianity’s enemies would have seized upon this evidence instantly; instead, every single one of them accepts Jesus as having been a real person without question.

In the second century AD, the Platonist philosopher Kelsos wrote a polemic entitled On the True Word in which he attacked Christianity as a false superstition. Nearly the full text of Kelsos’s book has been preserved because the church father Origen of Alexandria wrote a refutation to it entitled Against Kelsos in which he quoted almost every word, following each quotation with a lengthy rebuttal.

What is interesting is that, far from claiming that Jesus never existed, Kelsos instead declared that Jesus was the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier named Pandera and a magician who used clever tricks and black magic to fool people into thinking he was divine. Likewise, Jesus may be referenced in the Babylonian Talmud, which was composed between the fourth and sixth centuries AD. It would have been in every interest of the Jewish Rabbis to deny that Jesus ever existed, but, instead, they portray him as a sorcerer and a charlatan who led Israel astray.

A religion without a founder?

A somewhat weaker problem with the Mythicist argument is the fact that new religions are almost always led by a charismatic leader. There are a few exceptions, such as the cargo cults of Vanuatu, but these exceptions are rare and single leaders appear to be the norm.

When we notice the discrepancies between the teachings of John the Baptist, as recorded by the Synoptic Gospels and by Josephus, and the ideas behind early Christianity, we cannot help but conclude that there must have been an intermediate figure between the two, who introduced important ideas of his own. If Jesus did not exist, then who was the charismatic leader behind early Christianity? We know it could not have been Paul because Paul mentions in his letters that Christianity existed before him and that he had previously opposed the movement.

The main leaders before Paul were Jesus’s (alleged?) brother James, and his (alleged?) closest disciples Peter and John. Judging from Paul, James was clearly a great organizer and leader, but he hardly seems like someone who would come up with an whole new philosophy. Peter seems to have been a great compromiser, but a poor leader, let alone much of an innovator.

We do not know very much about John, but, if the writings later attributed to him tell us anything about his thought, he seems to have been largely an individualist. The most obvious person responsible for the differences between the apocalyptic Judaism of John the Baptist and pre-Pauline Christianity is clearly Jesus himself. For him to be responsible, of course, he would have to have existed.

The supposed pagan influence

A bizarre and inexplicable claim found among Mythicists of all varieties is the idea that Jesus was somehow modeled off previous pagan deities. This idea makes very little historical sense, since we know that the earliest Christians were devout Jews who utterly abhorred anything pagan. Nonetheless, this has not stopped the Mythicists from presenting their arguments to the contrary. In any case, the “pagan predecessor” argument proves absolutely nothing, since it at best merely shows that Jesus was just not perfectly unique. (Spoiler alert: No one is perfectly unique.)

I, unfortunately, do not have space to address all of the different deities that have been proffered over the years as “pagan predecessors” to Jesus, but they all generally rely on either extremely vague similarities or ones that have been wildly exaggerated out of proportion. Quite frequently, especially in online publications, parallels are simply invented out of whole cloth with no regard whatsoever for the truth. Here is an extremely brief survey of a tiny handful of the most popular:

Mithras

Despite all the stories Mythicists tell about him, we actually know very little about the cult of Mithras, primarily because it was a “Mystery Cult,” meaning its members were forbidden from telling others about it. We do know, based on the numerous surviving sculptures excavated from Mithraea (Mithraic places of worship) that Mithras was believed to have been born from a rock and that his primary feat was the slaying of a gigantic cosmic bull.

The main reason why Mythicists associate Jesus with Mithras is because early Christian apologists intentionally exaggerated the superficial similarities between Mithraism and Christianity in order to cast Mithraism as a “knock-off version” of Christianity created by Satan to lead people astray. They, for instance, claimed that the Mithraic cult had its own version of baptism and its own version of the Eucharist.

None of these apologists were ever actually members of the cult, indicating that their knowledge of it is probably nothing more than hearsay. There is evidence for some kind of ritual meals and purification ceremonies associated with the Mithraic cult, but, since these sorts of rituals were commonplace throughout many different cults of the time period, it is unlikely that these have any real connection to the Christian rituals bearing only superficial similarities to them.

ABOVE: This third-century AD Roman sculpture excavated from a Mithraeum depicts the famous tauroctony, or bull-slaying scene, that was central to the belief system of the Mithraic Cult.

ABOVE: Late second-century AD Roman sculpture from the Baths of Diocletian showing Mithras being born from the rock, another story that was important to the Mithraic cult

ABOVE: Late second-century AD Roman sculpture from the Baths of Diocletian showing Mithras being born from the rock, another story that was important to the Mithraic cult

Horus

Horus was a major deity in the ancient Egyptian pantheon. He was the god of the pharaoh and was represented with the head of a falcon. There are no real similarities between Horus and Jesus. All of the supposed “parallels” can be traced back to a nineteenth-century Spiritualist named Gerald Massey, who wrote three books entitled The Book of Beginnings, The Natural Genesis, and Ancient Egypt: The Light of the World, in which he asserted that all the religions practiced in all countries around the world are actually corrupted versions of ancient Egyptian paganism, which he insisted was the one true religion.

Massey had no professional training in Egyptology and his arguments are almost entirely based on erroneous information. For instance, he at one point argues that King Herod was not a real person either, despite the overwhelming historical documentation of Herod’s reign found in the writings of Josephus and the Jewish Middle Platonist philosopher Philon of Alexandria. The closest real similarity we find between Jesus and Horus is that Christians in late antiquity may have adapted depictions of the infant Horus to suit the infant Jesus, which, of course, only relates to later Christian portrayals of Jesus and has nothing to do with the real, historical Jesus.

Dionysos

Dionysos was the ancient Greek god of wine, drunkenness, and ritual ecstasy. Many scholars have seriously contended that the portrayal of Jesus in the Gospel of John may have been genuinely influenced by Dionysian symbolism. For instance, Jesus’s miracle of turning water into wine at the marriage in Cana in John 2:1-11 does bear a strong resemblance to a story of Dionysos turning water into wine for a poor herdsman in the Greek novel Leukippe and Kleitophon, which was written in the second century AD, and the Greek geographer Pausanias records a ritual in which Dionysos was said to fill empty barrels locked in a temple overnight with wine. Likewise, the parable of the “True Vine” in John 15:1-17 may have been written to imply that Dionysos was not the “True Vine.”

Some scholars, such as Mark W. G. Stibbe, have even argued that the Gospel of John may directly emulate Euripides’s tragedy The Bakkhai, in which Dionysos is the central character. There are two problems, however, that should be pointed out: First, all of this Dionysian imagery is solely found in the Gospel of John, the last of the four gospels, and we find very little, if anything at all, to indicate a Dionysian influence on the earlier gospels. Secondly, other scholars have quite convincingly argued that the wine imagery in the Gospel of John may just as plausibly stem from the Old Testament, which uses wine as a symbol for happiness.

ABOVE: Greek black-figure painting of Dionysos extending a kantharos drinking cup, dating to the late sixth century BC

Dumuzid/Tammuz/Adonis

Dumuzid the Shepherd, later known throughout the Levant as Tammuz, and to the Greeks as Adonis, was an agricultural fertility god associated with springtime, whose annual death was believed to be the cause of the long, dry summers of Mesopotamia when all the crops would wither and perish. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, he was considered to be the foremost example of a “dying-and-rising god” based on the assumption that the incomplete Akkadian abridged version of Inanna’s Descent into the Underworld would end with Inanna bringing Dumuzid back to life. Then, in the mid-twentieth century, the full, original Sumerian text behind Inanna’s Descent was translated, revealing that the story actually ended with Dumuzid’s death, not his resurrection.

In one later retelling, Inanna does allow Dumuzid to leave the Underworld for half the year, but only when his sister Geshtinanna takes his place. The story therefore merely affirms the inescapable power of the Underworld and does not contain any notions of “triumph over death.” Stories of Tammuz’s annual death and return may have influenced some later retellings of the passion narrative, such as those of the sixth-century AD Syrian writers Jacob of Serugh and Romanos the Melodist, but are highly unlikely to have influenced the actual accounts of Jesus’s suffering in the original gospels.

ABOVE: Mesopotamian cylinder seal impression depicting Dumuzid being tormented in the underworld by galla demons

Baldr

Baldr is a Norse god who, in the best-known version of his myths, is associated with truth, justice, morality, light, beauty, and lots of other warm, fuzzy things. Like Jesus, he is said to have suffered a tragic death. He was not crucified, however, but rather accidentally killed by his blind brother Höðr, who was tricked and manipulated by Loki. On the surface, Baldr bears a much closer resemblance to Jesus than any of the other deities I have examined so far; this, however, is because our main source of information about Baldr is the Prose Edda, a collection of traditional stories compiled in Iceland in around 1220 AD by an Icelandic antiquarian named Snorri Sturluson (lived 1179 – 1241). Snorri Sturluson was himself a Christian and, at the time when he lived, Iceland had been predominately Christian for several centuries.

Snorri was writing for a Christian audience and therefore deliberately altered many of the stories he recorded to make them more similar to Christian stories. Scattered evidence from earlier inscriptions and poems dating to the time before the Prose Edda indicate that Baldr was originally seen as a fierce warrior deity, not the loving, Christ-like figure Snorri portrays him as. In any case, there are no sources that even mention Baldr from before ninth century AD, which makes it questionable whether he was even worshipped by anyone on earth at the time when the books that later became incorporated into the New Testament were being written.

ABOVE: Late eighteenth-century Icelandic manuscript illustration depicting the death of Baldr at the hands of his brother Höðr

Occam’s razor

Mythicists frequently devise all sorts of bizarre and often ridiculous explanations for how Jesus still could have been an invention. These explanations do not hold up to scrutiny. Sure, it is hypothetically possible that the Catholic Church (or any of the numerous other historical bogeyman that internet conspiracy theorists love to pick on) might have somehow managed to systematically doctor all of the surviving documents as part of a massive conspiracy to cover up the secret of Christianity’s origins.

It is also equally hypothetically possible, however, that reptilian aliens from space brainwashed everyone to believe in Jesus using magic probes inserted through everyone’s nostrils. Obviously, neither of these are reasonable explanations. The simplest, most logical explanation for Christianity’s origins based on all the evidence currently available is that there was indeed a person named Jesus who really came from Nazareth, really taught at least some of the teachings ascribed to him in the gospels, and really was crucified.

ABOVE: Stained glass window of William of Occam, after whom Occam’s Razor is named

The reason?

The real reason why humanists and conspiracy theorists alike continue to insist that Jesus was not a real person is not because there is any logical reason for this conclusion; it is because they are trying to combat contemporary religious fundamentalism and the easiest way to destroy Christian fundamentalism is by “proving” that the religion’s putative founder never existed. In doing this, however, Mythicists are inadvertently exemplifying a disturbing trend in modern society, which is ignorance of ancient history, historical scholarship, and of the historical method in general.

As Maurice Casey, the late professor emeritus of New Testament Languages at the University of Nottingham, has thoughtfully highlighted, the major proponents of the Christ Myth theory all display a peculiar ignorance of critical Bible scholarship, a more than two-century old rigorous academic discipline based on the same tools originally developed for analyzing other classical texts.

Instead, Mythicists seem to assume that all Bible scholars are Christian fundamentalists. Even more bizarrely, they often seem to think that Jesus must have either lived and died and rose again in the exact way he is described by whatever specific Christian denomination they themselves happened to have been raised in, or else he could not have existed at all.

Further reading

The reasons for Jesus’s existence of a historical person which I have presented in this brief article are far from the only ones, but I do not have enough space to give a truly in-depth rebuttal to all the claims that I have encountered. For further information, I highly recommend reading Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth by Bart D. Ehrman and Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? by Maurice Casey, both of whom are renowned scholars on this subject.

I recommend reading Ehrman’s book first and then Casey’s, since Ehrman’s book is aimed at a popular audience; whereas Casey’s is more academic. Another useful book to read would be The Jesus Legend: The Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition by Paul Rhodes Eddy and Gregory A. Boyd, which discusses the issue of Mythicism, although it is more primarily concerned with defending the historical reliability of the Synoptic Gospels.

One other note that I have not seen mentioned is that the destruction of Jerusalem in 65-70AD (and other cities later as well) would have resulted in contemporary documents which may have existed being destroyed. (The Dead Sea Scrolls and related documents tend to be earlier.)

It is highly unlikely that there would have been any contemporary records of Jesus’s life, given that, as I explained in the article, he was hardly the sort of person who would have attracted much attention from ancient historians. Nonetheless, it is still entirely possible that there could have been and it is entirely possible that, if there were records, they could have been destroyed during the Jewish Revolt, since there was certainly a great deal of destruction during that conflict. Of course, the problem is that we cannot possibly know for certain and we cannot speculate about the existence of records that we do not have and have no evidence for. Thank you for commenting, though! I always love it when people comment on my articles!

Great article!

I think Ehrman’s book in particular is a good antidote to the over-enthusiasm of previously “born-again” fundamentalist Christian who have had the scales drop from their eyes and realize that so much of what they believed is nonsense, so maybe it’s ALL nonsense, since he himself is a former fundamentalist whose work shows that the real, actual human being on whom the Gospel accounts are based was so very different from the religious teachings of Christianity that it’s not really THAT far off to say “Jesus Christ never existed” — as long as you are quite clear that what you mean by that isn’t that there was no such person as Jesus of Nazareth, but that he wasn’t the “Jesus Christ” of the Christian religion.

I do think there’s a BIT of truth on the Mythicists side – most compelling falsehoods carry at least a seed of truth – in that I think it likely that some in the early Church deliberately incorporated certain things from various myths around them to broaden the appeal of their message. For instance, no one knows when Jesus was born, and if there is ANY truth in EITHER of the Gospel accounts probably wasn’t in the winter time. It was frankly probably in the spring, about the same time of year as Easter. But the Church already HAD a celebration in the spring. They wanted to have another celebration at another time of year. While having a big celebration near the Winter Solstice is so nearly universal that it needn’t necessarily be thought of as “pagan” influence, I do believe choosing the specific date of the Natalis Invicti festival couldn’t possibly have been just a coincidence.

John in particular I suspect of this sort of thing, not just with the Dionysian wine-making but other things as well. And the post-Constantine Roman Church was more about consolidation of power in its first few centuries than it was about finding spiritual truth.

Hmmm. Having read a couple of your other articles about the topic of Christmas and its traditions, I take back what I said about Sol Invictus. My first thought was that the *approximate* date (near Midwinter) was based on Saturnalia, but I knew that a) the dates don’t EXACTLY match up and b) Saturnalia was by far not the only midwinter festival in the world, so I thought it unlikely to have been the reason for the date. The more I think about it, though, the more I think that a) the primary reason for choosing a midwinter date for a celebration of Jesus’ birth was in fact the universality of people wanting a holiday then and b) of those celebrations, the one they would most likely have been influenced by was Saturnalia, so I think that – exact dates aside – that probably WAS the reason for the choice.

This of course has nothing to do with whether or not Jesus is a myth, which I think is a ridiculous idea. That early Church fathers, deliberately or by cultural osmosis, *absorbed* certain mythic elements of the world around them into Christianity seems not just likely but almost undeniable, but that they created the entire figure and ministry of Jesus out of whole cloth seems preposterous.

• Richard Carrier opines that Bart Ehrman is trying to build history from a self created myth about evidence and that Ehrman fully believes in this evidence-myth @time 38-minutes, 52-seconds. [END @ 00:43:00]

“Richard Carrier Vs Bart Ehrman: Did Jesus Exist? (Re-edited)”. YouTube. MythVision Podcast. 24 November 2018.

Salutations Spencer Alexander McDaniel,

• IMO, scholars such as Bart D. Ehrman and Maurice Casey have failed you. I hope one future day to read your magnum opus, whatever topic it may be.

Cf. Lataster, Raphael (2019). Questioning the Historicity of Jesus: Why a Philosophical Analysis Elucidates the Historical Discourse. BRILL. ISBN 9789004408784. “This volume explains the inadequacy of the sources and methods used to establish Jesus’ historicity, and how agnosticism can reasonably be upgraded to theorising about ahistoricity when reconsidering Christian Origins.”

I would disagree, but, regardless of whether these scholars have “failed me” or not, I do not plan on discussing this subject at any great length anytime in the immediate future. I believe that, despite a few flaws that have already been pointed out, my argument still largely stands. As I noted previously, I think Carrier’s article had one or two good points, but I think that there were also a great many flaws in it and that his larger argument is still incorrect.

In the meantime, I do not enjoy having hundreds of people mocking me and angrily criticizing me for my alleged ignorance in lengthy comments sections or on Reddit (as they are now doing). As of right now at least, I intend to try to confine my future writing on this website to less politically and religiously controversial subjects than the historicity of Jesus, which seems to be perhaps the one subject in the entire field of ancient history that is the most capable of consistently inciting outrage and controversy.

You may notice that I have not written about anything terribly controversial lately. My most recent article is about misattributed ancient quotes; my last article before that was about why so many ancient sculptures have missing noses; and my last article before that was about modern misconceptions about the Library of Alexandria. I am hoping these kinds of articles will be popular, but that they will not incite the same sort of ire and controversy as this article seems to have attracted.

It should be noted that I have now removed all personally derogatory comments about Carrier from this article. I have also deleted several answers that I wrote on Quora in which I was critical of Carrier. I do not wish to start a rivalry here. I have already seen the intense hatred that runs between Richard Carrier and Tim O’Neill and I have no intention of attracting that kind of bitter hostility.

Have you seen Richard Carrier’s response to this? https://www.richardcarrier.info/archives/15563

Yes. I have. I got on my website early this morning to publish my most recent article, which is about Roman emperors, only to discover that I had two new comments on my website, both of them mentioning Carrier’s article. I did a Google search for my name and his and the article he wrote yesterday came right up as the first item. I read Carrier’s entire post several times over. I was pleasantly surprised to find that he actually had a few nice things to say about me, even though he mostly had only criticism.

I actually tried to leave a comment underneath his post, but I am not sure if the comment went through or if it was automatically blocked as spam, since, so far, it is not showing up on his website. I know that many comments people try to leave on my website unfortunately end up getting automatically blocked as spam and I never see them. I also know that the comments section on his website says “For Patrons & Select Persons Only.” I am not a patron of his website and I am not sure if I qualify as a “select person,” even though the entire article he wrote was criticizing what I wrote in the article above. Here is the full text of the comment I tried to leave:

Although I did not hesitate to express my profound disagreement with him on this issue, as well as my genuine astonishment to find him attacking me of all people, given how few people read my website, I tried to take a conciliatory tone—something along the lines of, essentially, “We will just have to agree to disagree.” I have no idea how Carrier will react to this, if he even sees it. As I said before, I am genuinely surprised that he even found out my website existed and even more surprised that he chose to respond to what I had written.

Why did he respond? My guess is it has something to do with “Blogger and atheist activist Richard Carrier (who, to his credit, does have a PhD in ancient history, though he is currently unemployed and his reputation in scholarly circles could not be much lower).” Wow. That’s really, really harsh. It would certainly get MY attention, and I can understand the impulse to squash you like a bug in response (which, no doubt, he believes he has done).

Of course, he also tends to hyperbolic insults casually cast at those he disagrees with (“I strongly suspect McDaniel foolishly trusted that crank amateur liar Tim O’Neill”), so those who live in glass houses …

I read his entire piece. I wasn’t impressed. His continual insistence on the phrase “peer-reviewed” throughout in reference to his own works I found tiresome, his thesis unconvincing, and one of the few citations I bothered to look up refuted what he said about it, in my opinion. His fantastical argument that Jesus’ suffering and death were real but took place in the Heavens and were revealed to Peter and James through visions (if I’m understanding him – this is the first time I’ve ever read extensively anything he has written) I find bizarre and frankly laughable. Occam’s razor alone would tell you that a real historical Jesus is more likely than that!

You’re not only an undergrad but were in high school when you launched this project? Goodness gracious! As a 60+ lifetime aficionado of history (though one with little formal training – my own degree is in English Literature) for whom the Greco-Roman world is one of my abiding interests (my primary one being late-medieval early-Renaissance Italy, but also the long histories of Egypt and Mesopotamia and of course because of its impact on the literature the history of England), I think you’re doing an excellent job. Don’t let the harsh words of a crank – even if he IS a professional crank – get you down!

Thank you so much for your kind words and support! In regards to my rather unkind remark about Carrier in this article, I have to honestly admit that I actually completely forgot I said that about him. You have to remember that I originally wrote this article over a year ago. Now, though, I think I understand at least part of the reason why Carrier chose to respond to me. Actually, I am rather surprised that, after what I said about him, he was so complementary about my other articles. He even said he liked my article I wrote last month in which I defend the historicity of Alexander the Great. If you read his article he linked in which he attacks Tim O’Neill, you will notice that he does not hold back the insults at all; in the very first paragraph, he calls O’Neill “an asscrank, a total tinfoil hatter, filled with slanderous rage and void of any competence and honesty.” I suppose I should be glad he only accuses me of naïvety, gullibility, bad research, and fallacious reasoning.

As I state in my comment that I posted on Carrier’s webpage, which I have quoted in my comment above, I do think Carrier did have a few good points, but I still think his overall argument is wrong. I also noticed several flaws in reasoning in his article. I do not think I will write a response to Carrier’s article, however. If I were to write a response, he would probably write another article criticizing my response and the argument would just go on and on and on. There are other things I would much rather write about than the historicity of Jesus. Unlike Carrier, it seems, I do not enjoy arguing about extremely politically and religiously controversial subjects.

Actually, one of the main reasons why I wrote this article to begin with was because I was tired of arguing around in circles with people on the internet about the historicity of Jesus, so I decided to just summarize my usual arguments in one article. That way, I could direct anyone I was in an argument with to this article so that I would not have to waste as much time arguing with them. I was not expecting the article to provoke a lengthy response from anyone, let alone Richard Carrier, who I did not think would even read my article.

Good article. Your objective was to explain why almost all Bible scholars think Jesus existed and you’ve done that. The disconnect between Believers and Skeptics is each tends to strawman the other side. Believers tend to posture that Skeptics think it likely that Jesus did not exist and Skeptics tend to posture that Believers think it a proven fact that Jesus existed.

So rather than assume I’ll just ask if you are a Believer or Skeptic and do you think it a proven fact that Jesus existed?

Good grief, this is gauche.

Take Mark W. G. Stibbe:

The first hit I got with the search string Mark W. G. Stibbe + Dionysus + Jesus returned https://vridar.org/2013/05/09/jesus-and-dionysus-2-comparison-of-johns-gospel-and-euripides-play/, where we can see straight away that:

is not Stibbe’s argument at all from direct quotes of Stibbe.

Neil Godfrey’s further summary shows Stibbe to be no sort of “Jesus Mythicist” and making no arguments that could be even construed as supporting such.

If you are going to leave this up, I’m going to have to disagree with my mate Richard: with research “skills” like this you will make no sort of scholar. Even by the lax standards of New Testament Studies; this is tosh. By the standards of my grammar school education; this is tosh.

Do yourself a favour: if you even wish to scrape a Third; acquire some at least notional research skills and demonstrate at least a nodding accurate acquaintance with the texts and scholars you claim to be critiquing.

I never said that Mark W. G. Stibbe was a “Jesus Mythicist”; on the contrary, I cited him as an example of a real scholar who has argued that the Gospel of John has been influenced by Euripides’s Bakkhai. As for your accusation that I did not accurately represent his argument in this article, I am not sure what about it you think I failed to accurately represent. Stibbe argues that the Gospel of John contains themes, elements, and passages that echo Euripides’s Bakkhai, which is what I said he was arguing.

I will ignore your other remarks about how you think that I will never be scholar, that everything I write is “gauche” and “tosh,” and that I lack even “notional research skills.”

• McDaniel is correct, Watson is not.

OP: “Some scholars, such as Mark W. G. Stibbe, have even argued that the Gospel of John may directly emulate Euripides’s tragedy The Bakkhai, in which Dionysos is the central character.”

MacDonald, Dennis R. (2017). “The Dionysian Gospel: The Fourth Gospel and Euripides”. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781506421667.

Salutations Spencer Alexander McDaniel,

If a scholar is contractually obliged to publicly reject any Jesus ahistoricity theory. (see: Fitzgerald, David (2017). “Myths of Mythicism – Bias Cut”. Jesus: Mything in Action. 1. CreateSpace. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-5428-5888-5.)

• What is your position on the public condemnation of said scholar, would you denounce the scholar, the institution, and the enablers that are party to such a censorship of free thought?

Dear Spencer,

Today I read your article above and Richard Carrier’s criticisms of it. I found yours more convincing. I had particular difficulties with Carrier’s argument under the heading “Getting missing data wrong”, but perhaps I misunderstood it. It appears to say that we know or suspect that there were sects in existence in the first one hundred years after the death of Christ which were antithetical to Christianity, that no writings of such sects survived, that, therefore, such writings were destroyed, and, therefore, we should infer such writings would have refuted the earthly existence of Christ. Is that the gist of it do you think?

I am impressed by your apparent learning at such a tender age and expect a remarkable career. I note that you say you would improve on your above article if you wrote it now. For my own benefit, I would urge you to do so.

Be that as it may, I was surprised that both you and Carrier dismiss much weight being placed on the writings of Tacitus and Pliny. Josephus, Pliny, Tacitus, and Suetonius were writing histories, largely contemptuous of the new religion, as closely in time to the life and death of Christ as we could reasonably expect. Certainly Tacitus had access to what records there were. None of them had any motivation to lie or exaggerate about the existence of Christ and his execution by crucifixion under Pontius Pilate. I would have thought that was compelling evidence ?

I must add that I felt compelled to write this note because you say you have received hundreds of mocking and angry replies to your calm and reasoned and learned article. In my view people of your calibre must be encouraged. I am of a far more advanced age than you and recall a time when debates could be carried out in a polite and reasoned manner. Let’s hope that custom returns, eh?

Regards, MW

Thank you so much! That is so very kind of you! It makes me feel good to hear another person say that.

I do not believe I ever said that I had received “hundreds of mocking and angry replies” on this article; if I did say that, that would have been an exaggeration. All comments that I have received on this article so far have been published and are visible here in this comments section underneath the article—even the most vitriolic of them. I am not the sort of person who likes to silence my critics, so what you see here is the full extent of everything people have submitted to me as comments. Nonetheless, as you can tell, I have indeed received quite a few comments on this article that are very negative.

The vast majority of the mockery of me over this article seems to be taking place on other websites. For instance, you can just look at the lengthy comments section under Carrier’s article to get a taste. There is also a Reddit page on r/atheism that is basically all pro-Carrier, with some disparaging comments about me mixed in. Then there is also the comments section under a post Neil Godfrey did about Carrier’s article, where some other people have left rather disparaging comments about me.

I suppose that what shocked me after Carrier’s article was published was not so much the actual things people were saying, but rather more the fact that there was such widespread criticism being published on other websites concerning something I had written. Prior to this summer, I was accustomed to thinking of my website as an obscure, small-time blog. I never expected Richard Carrier to even find out I existed, let alone write a rebuttal to me.

I guess it shocked me that I was getting so much attention at all on other websites. It shocked me even more that I was getting so much negative attention. Now my little blog here seems to be getting a lot more attention than it used to. I think most of that attention is coming from my followers on Quora, but it is certainly possible that Carrier’s article may have, ironically, boosted attention to my website somewhat.

Dear Spencer

The internet is a monster created by my generation but one that yours will have to learn to deal with or, at least, to live with.

I wonder if you have ever watched a TV series called “West Wing” ? It’s now probably regarded as old hat , and it wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea anyway, but I enjoyed it. In one episode, a main character (Josh Lyman) realises that he has attracted the attention of an internet site and he decides to post his own comment on it, against the sage and prescient advice of another main character ( Donna Moss), who explains that he will become the object of extraordinarily unreasonable attacks and criticisms. The episode, I believe, correctly reflects the world of the internet, unfortunately.

Nevertheless, I urge you to keep up the good work. The world will be a better place for your kind of writings.

I dare say you have a lot of study and reading and writing and other activities on your plate, but I note you haven’t addressed a couple of questions of mine. I’d like the benefit of your thoughts, be they dismissive of mine, but only when you have time.

Regards, MW

• Per Carrier, “Dependent evidence has zero value in Bayesian estimates of likelihood (OHJ, Ch. 7.1).”

• Per Carrier, “almost all evidence of the original Christian sects and what they believed has been lost or doctored out of the record; even evidence of what happened during the latter half of the first century to transition from Paul’s Christianity to second-century ‘orthodoxy’ is completely lost and now almost wholly inaccessible to us (Elements 21-22 and 44).”

• Per Carrier:

As far as I can tell, the passages from Carrier that you have just quoted here basically seem to support what Michael Waugh has stated above.

Salutations Spencer Alexander McDaniel,

• Per the first point made by Michael Waugh.

It is not possible to prove that Josephus’ testimony and other non-Christian sources are independent of the Gospels (and Gospel-dependent Christian legends and informants). Therefore under standard academic historical methodology, they are not considered as attestation for the historicity of Jesus.

• I am currently discussing this point in more detail with Dr Sarah, and we are waiting on a response from Richard Carrier.

“Comment by db—3 December 2019”—per “‘Deciphering The Gospels Proves Jesus Never Existed’ review: Intro/Chapter One”. Geeky Humanist. 3 December 2019.

I actually don’t entirely disagree with what you say about Josephus being a red herring. I do think that Josephus is relevant to the discussion of the historicity of Jesus, but I also think that he tends to get vastly more attention than he probably deserves. Many apologists seem to point to Josephus’s testimony as though it were definitive proof on its own that Jesus really existed.

Meanwhile, many Mythicists go to great lengths trying to prove that the two mentions of Jesus in Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews are both later insertions when, in fact, I don’t think that is a very productive course of action for them to take. Once again, I do think that Josephus is relevant to this discussion, but I don’t think he is as important as many people perceive him as being.

For what it is worth, I still think that the Testimonium Flavianum is partially authentic (or that it has, at the very least, replaced an authentic passage in which Josephus mentioned Jesus) and I still think that the James reference is completely genuine. I don’t think that either of those references on their own, though, can definitively prove that Jesus existed.

I do still think that there was probably a single historical figure named Jesus who provided much of the basis for the later Christian conception of Jesus, but, as of right now, I plan to avoid this subject as much as possible in the future because have honestly grown rather sick of all the bitterness and toxicity that the subject of the historicity of Jesus inevitably engenders.

The historicity of Jesus is a subject that seems practically impossible to debate civilly because everyone has such strong opinions on it. I still think that there probably was a single historical figure who served as an inspiration for the Christian conception of Jesus, but, at this point, I’m tired of the debate and I know nothing I say can convince anyone.