On 15 March 44 BC, an event happened that changed history forever: a group of over thirty conspirators led by Gaius Cassius Longinus, Marcus Junius Brutus the Younger, and Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus assassinated the Roman politician and general Gaius Julius Caesar in the Theater of Pompey. It is an assassination that has gone down as one of the most famous in history. The assassination of Julius Caesar has been the subject of countless plays, books, films, television shows, and even video games.

Partially reinforced by these takes on Caesar’s assassination in popular culture, many people mistakenly believe that Julius Caesar’s last words were, “Et tu, Brute?” which means, “And you, Brutus?” in Latin—allegedly an expression of shock and horror at Marcus Junius Brutus’s betrayal. In reality, however, the historical Julius Caesar never uttered these words; no one knows what Caesar’s real last words were, but ancient writers attribute a number of different phrases to him in the moments leading up to his death.

“Et tu, Brute?”

The phrase “Et tu, Brute?” is never at any point attributed to Julius Caesar in any surviving ancient text. None of the surviving accounts of Caesar’s murder mention it and it is never attributed to him anywhere else. Instead, this famous phrase comes from Act III, Scene I of the tragedy Julius Caesar, which was written by the English poet and playwright William Shakespeare (lived 1564 – 1616), probably in around the year 1599 or thereabouts. Even in the play, however, this famous phrase is still not the last thing Julius Caesar says before he dies. The full macaronic line actually reads:

“Et tu Brute?

Then fall Caesar.”

These words, however, are entirely fictional; as I said earlier, they do not appear in the writings of any Greek or Roman historians. Shakespeare just made this whole line up for dramatic effect.

“And you, child?”

Julius Caesar definitely never said, “Et tu, Brute?” Nonetheless, the ancient Roman historian Gaius Suetonius Traquillus (lived c. 69 – after c. 122 AD) does report in his biography The Life of Julius Caesar that some people attributed a vaguely similar expression to Caesar as his last words. Suetonius states that some people claimed that, when Julius Caesar saw that Marcus Junius Brutus was among the conspirators, he uttered the Greek words “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον” (kaì sý, téknon).

This phrase, which Suetonius claims some people attributed to Caesar, literally means, “And you, child.” Nonetheless, Suetonius gives no further explanation of what people believed this phrase was supposed to mean. There is still ongoing debate among classical scholars as to what these words are supposed to have meant in context. The ancient Greeks and Romans did not use question marks, so it is unclear if the phrase is meant as a question.

ABOVE: Roman silver denarius minted in either 43 or 42 BC, bearing the portrait of Marcus Junius Brutus the Younger on the obverse. According to Suetonius, some people believed that Julius Caesar had uttered the phrase “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον” to Brutus just before he died.

If the phrase is interpreted as a question, then we might regard it as an expression of astonishment by Caesar that even Marcus Junius Brutus, who was one of Caesar’s most trusted friends, was a member of the conspiracy. If this is the case, then the phrase could be interpreted as meaning more-or-less the same thing as the expression “Et tu, Brute?” from Shakespeare’s play.

Alternatively, however, the same phrase could also be interpreted as a prediction of Marcus Junius Brutus’s imminent demise. It is possible that the people who originally told this story believed that Caesar had said, “And you, child!” as in, “You, child, will die soon too!” Ultimately, Brutus committed suicide on 23 October 42 BC after his forces were soundly defeated by the forces of the Second Triumvirate in the Battle of Philippi. This interpretation would give the phrase “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον” a much darker, more ominous meaning than the more familiar interpretation of it as a mere expression of astonishment.

The scholar A. J. Woodman has plausibly speculated that the phrase “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον” may, in fact, be a quotation from a now-lost ancient Greek poem in dactylic hexameter, possibly an epic composed during the Hellenistic Period. Drawing on other quotations found in Roman-era literature containing the phrase “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον,” Woodman reconstructs the full hexameter line as “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον, ποτὲ τῆς ἀρχῆς ἡμῶν παρατρώξῃ.” This means, “And you, child, will someday have a taste of our power.”

If this argument is correct, then the people who told this story about Caesar saying “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον” to Brutus must have seen it neither as an exclamation of surprise nor as a prediction of Brutus’s downfall, but rather as an erudite denunciation of Brutus’s motives. Brutus claimed that he killed Julius Caesar to prevent him from becoming a tyrant, but Caesar quoting this line to Brutus at the moment of his assassination would clearly carry the implication that, in Caesar’s view, Brutus was really doing it out of selfish desire for power.

ABOVE: Color lithograph illustration by William Rainey for the children’s book Plutarch’s Lives for Boys and Girls by W. H. Weston, depicting the defeated Brutus with his companions after the Battle of Philippi

He probably didn’t say that either, though…

Unfortunately for those among us who love a good dramatic moment, it is highly unlikely that Julius Caesar really said “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον” either. Indeed, the idea of Caesar saying “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον” is only slightly less implausible than the idea of him saying “Et tu, Brute?” Even Suetonius, the very author who reports the story that Julius Caesar said “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον,” intentionally seems to distance himself from it. Rather than presenting this story as fact, Suetonius seems to present it as nothing more than a speculative rumor. Here is what Suetonius writes in section eighty-two of his Life of Julius Caesar:

“Assidentem conspirati specie officii circumsteterunt, ilicoque Cimber Tillius, qui primas partes susceperat, quasi aliquid rogaturus propius accessit renuentique et gestu in aliud tempus differenti ab utroque umero togam adprehendit; deinde clamantem: “Ista quidem vis est!” alter e Cascis aversum vulnerat paulum infra iugulum. Caesar Cascae brachium arreptum graphio traiecit conatusque prosilire alio vulnere tardatus est; utque animadvertit undique se strictis pugionibus peti, toga caput obvolvit, simul sinistra manu sinum ad ima crura deduxit, quo honestius caderet etiam inferiore corporis parte velata. Atque ita tribus et viginti plagis confossus est uno modo ad primum ictum gemitu sine voce edito, etsi tradiderunt quidam Marco Bruto irruenti dixisse: καὶ σὺ τέκνον; Exanimis diffugientibus cunctis aliquamdiu iacuit, donec lecticae impositum, dependente brachio, tres servoli domum rettulerunt. Nec in tot vulneribus, ut Antistius medicus existimabat, letale ullum repertum est, nisi quod secundo loco in pectore acceperat.”

Here is the same passage, as translated into Modern English by J. C. Rowlfe for the Loeb Classical Library:

“As he took his seat, the conspirators gathered about him as if to pay their respects, and straightway Tillius Cimber, who had assumed the lead, came nearer as though to ask something; and when Caesar with a gesture put him off to another time, Cimber caught his toga by both shoulders; then as Caesar cried, “Why, this is violence!” one of the Cascas stabbed him from one side just below the throat. Caesar caught Casca’s arm and ran it through with his stylus, but as he tried to leap to his feet, he was stopped by another wound. When he saw that he was beset on every side by drawn daggers, he muffled his head in his robe, and at the same time drew down its lap to his feet with his left hand, in order to fall more decently, with the lower part of his body also covered. And in this wise he was stabbed with three and twenty wounds, uttering not a word, but merely a groan at the first stroke, though some have written that when Marcus Brutus rushed at him, he said in Greek, ‘You too, my child?’ All the conspirators made off, and he lay there lifeless for some time, and finally three common slaves put him on a litter and carried him home, with one arm hanging down. And of so many wounds none turned out to be mortal, in the opinion of the physician Antistius, except the second one in the breast.”

Suetonius’s apparent skepticism towards the story is especially significant considering that Suetonius is known for retelling salacious anecdotes from unreliable sources. (For instance, as I discuss in this other article I wrote, Suetonius is our main source for many of the more bizarre and salacious stories about the alleged sexual depravities of Roman emperors.) The fact that Suetonius treats this particular story with skepticism suggests that his sources for it were especially untrustworthy. The last statement that Suetonius attributes to Caesar without skepticism is “Ista quidem vis est!” which is Latin for “Why, this is violence!”

Another reason to suspect that Julius Caesar probably never actually spoke the phrase “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον” is because this alleged statement is not mentioned by any other of our earliest sources aside from Suetonius, who, as I mentioned, is not well-known for his accuracy. The Greek historian Ploutarchos of Chaironeia (lived c. 46 – c. 120 AD), who is often considered a more reliable historian than Suetonius, also wrote a detailed account of the murder of Julius Caesar in his biography The Life of Julius Caesar. Ploutarchos, however, never mentions anything about Caesar saying “καὶ σὺ τέκνον.”

Even if we leave all these facts aside, the story itself is inherently implausible. If someone is in the middle of getting repeatedly stabbed in the torso with knives, that person is almost certainly not going to be able to say anything at all, let alone say something intelligible in a foreign tongue. It is simply not going to happen. Even if the person is able to speak, the identity of the person stabbing him is probably not going to be the first thing on his mind. The first thing on his mind is most likely going to be something more like, “Oh gosh, I’ve just been stabbed!” or “Help!”

Finally, if the phrase “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον” is correctly interpreted as a prediction of Brutus’s eventual suicide, then this would give us good reason to believe that this phrase probably only came to be attributed to Julius Caesar after Brutus had already committed suicide, since it is more likely that people would make up a post hoc story attributing an accurate prediction to Caesar than it is that Caesar actually made an accurate prediction—however vague—with his dying breath.

ABOVE: Color lithograph illustration by William Rainey for the children’s book Plutarch’s Lives for Boys and Girls by W. H. Weston, depicting the murder of Julius Caesar

Ploutarchos’s account of Caesar’s death

I have already quoted Suetonius’s account of the assassination of Julius Caesar. Here is Ploutarchos’s account, which is found in chapter sixty-six, sections four through fourteen of his biography The Life of Julius Caesar, which is included as part of his Parallel Lives of Famous Greeks and Romans. The original account is in Greek. The following is from Bernadotte Perrin’s English translation for the Loeb Classical Library:

“Well, then, Antony, who was a friend of Caesar’s and a robust man, was detained outside by Brutus Albinus, who purposely engaged him in a lengthy conversation; but Caesar went in, and the senate rose in his honour. Some of the partisans of Brutus took their places round the back of Caesar’s chair, while others went to meet him, as though they would support the petition which Tullius Cimber presented to Caesar in behalf of his exiled brother, and they joined their entreaties to his and accompanied Caesar up to his chair. But when, after taking his seat, Caesar continued to repulse their petitions, and, as they pressed upon him with greater importunity, began to show anger towards one and another of them, Tullius seized his toga with both hands and pulled it down from his neck. This was the signal for the assault. It was Casca who gave him the first blow with his dagger, in the neck, not a mortal wound, nor even a deep one, for which he was too much confused, as was natural at the beginning of a deed of great daring; so that Caesar turned about, grasped the knife, and held it fast. At almost the same instant both cried out, the smitten man in Latin: ‘Accursed Casca, what does thou?’ and the smiter, in Greek, to his brother: ‘Brother, help!’ [i.e. “ἀδελφέ, βοήθει”]”

“So the affair began, and those who were not privy to the plot were filled with consternation and horror at what was going on; they dared not fly, nor go to Caesar’s help, nay, nor even utter a word. But those who had prepared themselves for the murder bared each of them his dagger, and Caesar, hemmed in on all sides, whichever way he turned confronting blows of weapons aimed at his face and eyes, driven hither and thither like a wild beast, was entangled in the hands of all; for all had to take part in the sacrifice and taste of the slaughter. Therefore Brutus also gave him one blow in the groin. And it is said by some writers that although Caesar defended himself against the rest and darted this way and that and cried aloud, when he saw that Brutus had drawn his dagger, he pulled his toga down over his head and sank, either by chance or because pushed there by his murderers, against the pedestal on which the statue of Pompey stood. And the pedestal was drenched with his blood, so that one might have thought that Pompey himself was presiding over this vengeance upon his enemy, who now lay prostrate at his feet, quivering from a multitude of wounds. For it is said that he received twenty-three; and many of the conspirators were wounded by one another, as they struggled to plant all those blows in one body.”

As you can tell from reading the passage I have just quoted, Ploutarchos makes no mention of Caesar saying either “Ista quidem vis est!” or “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον.” Instead, Ploutarchos claims that, after being stabbed in the neck by Casca, Caesar cried out in Latin “Accursed Casca, what does thou?” In Ploutarchos’s original Greek, this is, “μιαρώτατε Κάσκα, τί ποιεῖς;”

This exclamation, however, is not reported by Suetonius. Instead, Suetonius states that Caesar simply impaled Casca’s arm with his writing stylus, which sounds rather more probable considering that he was struggling for his life.

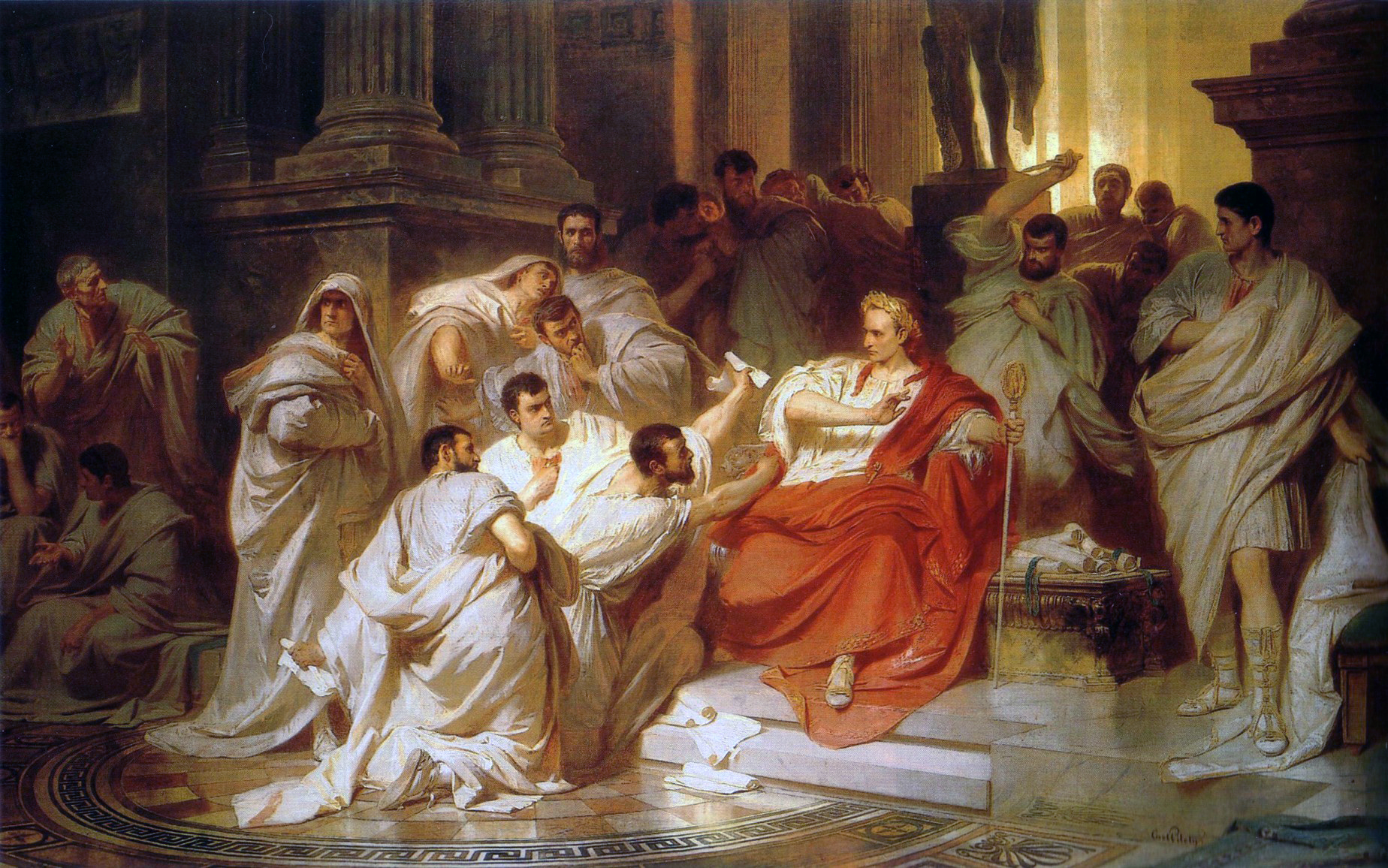

ABOVE: The Death of Caesar, painted in 1865 by the German Academic painter Karl von Piloty

Kassios Dion’s account of Caesar’s death

Suetonius and Ploutarchos’s accounts are our earliest detailed accounts of Julius Caesar’s murder, but they are not the only surviving accounts. In addition to Suetonius and Ploutarchos’s accounts, we also have a significantly later account written by the Greek historian Kassios Dion (lived c. 155 – c. 235 AD). This account occurs in Kassios Dion’s Roman History, Book Forty-Four, chapter nineteen.

Like Suetonius, Kassios Dion does mention the story claiming that Julius Caesar said “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον,” but he totally dismisses as it as a mere legend. He explicitly states that “the truest account” is that Caesar said nothing as he was being stabbed. Here is Kassios Dion’s account, as translated by Earnest Cary for the Loeb Classical Library:

“Now when he finally reached the senate, Trebonius kept Antony employed somewhere at a distance outside. For, though they had planned to kill both him and Lepidus, they feared they might be maligned as a result of the number they destroyed, on the ground that they had slain Caesar to gain supreme power and not to set free the city, as they pretended; and therefore they did not wish Antony even to be present at the slaying. As for Lepidus, he had set out on a campaign and was in the suburbs. When Trebonius, then, talked with Antony, the rest in a body surrounded Caesar, who was as easy of access and as affable as any one could be; and some conversed with him, while others made as if to present petitions to him, so that suspicion might be as far from his mind as possible. And when the right moment came, one of them approached him, as if to express his thanks for some favour or other, and pulled his toga from his shoulder, thus giving the signal that had been agreed upon by the conspirators. Thereupon they attacked him from many sides at once and wounded him to death, so that by reason of their numbers Caesar was unable to say or do anything, but veiling his face, was slain with many wounds. This is the truest account, though some have added that to Brutus, when he struck him a powerful blow, he said: ‘Thou, too, my son?'”

ABOVE: The Death of Caesar, painted between 1804 and 1805 by the Italian Neoclassical painter Vincenzo Camuccini (lived 1771 – 1844)

According to Ploutarchos, after the assassination was completed, Brutus stepped forwards as though he wished to make an announcement, but instead all the other conspirators fled, rushing out into the streets with their hands still dripping with Caesar’s blood. Brutus shouted out to the people of Rome that they were “once again free.” Suetonius reports that Caesar’s corpse lay in the Theater of Pompey for quite some time before it was eventually carried off on a liter by three slaves with one arm still hanging out.

As soon as he learned that Caesar had been assassinated, Marcus Antonius swiftly fled Rome disguised as a common slave, believing that Caesar’s assassination would result in a systematic massacre of Caesar’s supporters. The conspirators, meanwhile fearing that the common people would rise up and slaughter them, barricaded themselves inside the Capitol building for their own protection. When the bloodbath he had been anticipating did not ensure, Marcus Antonius returned to Rome to begin the long process of negotiating with the conspirators.

ABOVE: The Dead Body of Caesar, painted before 1920 by the Croatian symbolist painter Bela Čikoš Sesija

Conclusion

We do not know what Julius Caesar’s real last words were. It is doubtful we will ever know. When it comes to the exact words spoken on the occasion, the ancient historians who wrote about Julius Caesar’s assassination give differing reports. All we can be absolutely sure of is that Julius Caesar definitely did not say “Et tu, Brute?” and he probably did not say “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον” either.

This was really interesting. It does appear that certainly Shakespeare read all of the accounts you mention (or they were already incorporated in the canon of the 1500’s) because many elements of their descriptions do appear in the play. What playwright could pass up the words “Et tu, Brute” though? Brutus turns out to be equally flawed and tragic in different ways and those three words help to set up the play’s trajectory.

Amazing article. Very interesting fact about Caesar’s last words « kai sy, teknon ». I am a bit surprised though that scholars are puzzled about the real meaning of these words. I speak Greek and to me these words express Caesar’s surprise, not to say bitterness at the fact that someone so close to him, almost as close as a son, is there to give him the last blow. In this case, I think the word « teknon » which literally means « child », is used in free speech with the looser meaning of

« son ». Even in our days one can Call a younger person

« son ». « Kai sy » literally means « and you », but with a certain tone of the voice, can mean « even you ». Unfortunately without a proper ponctuation we cannot have the certainty, but I’d say that Caesar’s last words were of bitter deception and astonishment at the sight of Brutus ready to stab him. Caesar meant

« even you, son? »…