The trope that dragons are naturally obsessed or infatuated with treasure is absolutely pervasive throughout modern fantasy literature. You can pick up just about any modern book that has dragons in it and, more likely than not, the dragons will be obsessed with hoarding treasure of some kind. In this post, I will discuss where this trope originates from and how it became so ubiquitous.

In ancient Greece and Rome, drakontes (the ancient precursors of dragons) were primarily thought to serve as guardians, sometimes of treasure. The notion that dragons are obsessed with treasure seems to have arisen in classical antiquity or earlier as one of several different explanations for why they guard it. Thanks primarily to the Old English epic poem Beowulf and J. R. R. Tolkien’s 1937 children’s fantasy novel The Hobbit, which drew extensive inspiration from Beowulf, this explanation has now become accepted as standard in western popular culture.

Drakontes in ancient Greek and Roman mythology

The English word dragon comes from the Latin third-declension masculine noun draco, which comes from the Ancient Greek third-declension masculine noun δράκων (drákōn). The ancient Greeks typically imagined drakontes (which is the plural form of drakōn) as giant serpents with frills on their necks and beards on their chins. In some artistic depictions, drakontes are shown without neck frills, but they are nearly always bearded.

In ancient Greek myths and literature, drakontes are primarily said to serve as guardians. The word δράκων itself is traditionally thought to derive from the aorist active participle of the partially deponent verb δέρκομαι (dérkomai), meaning “to watch.” The word itself therefore literally indicates a creature that watches over something and protects it. In many ancient sources, drakontes are described as never sleeping and instead remaining perpetually alert.

The main secondary source I will be relying on for this post is the excellent and thoroughly comprehensive book Drakōn: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds by Daniel Ogden, published in 2013 by Oxford University Press. This post especially draws on Ogden’s chapter “Treasure without, treasure within” (pages 173–178), which discusses the idea of drakontes guarding treasure in ancient Greek and Roman sources.

ABOVE: Image of the front cover of the book Drakōn: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds by Daniel Ogden

Ladon and the golden apples

In many Greek myths, drakontes are specifically said to guard treasure. For instance, the drakōn Ladon, who is said in some accounts to have possessed one hundred heads, is said to guard a tree with golden apples in the Garden of the Hesperides. The eleventh of the Twelve Labors of Herakles is said to have been to retrieve these apples.

The myth of Ladon guarding the golden apples is first attested in the narrative poem Theogonia, attributed to the poet Hesiodos of Askre. The poem is composed in dactylic hexameter and most likely became fixed in something resembling its extant form sometime around the early seventh century BCE or thereabouts. It declares, in lines 333–335:

“Κητὼ δ᾽ ὁπλότατον Φόρκυι φιλότητι μιγεῖσα

γείνατο δεινὸν ὄφιν, ὃς ἐρεμνῆς κεύθεσι γαίης

πείρασιν ἐν μεγάλοις παγχρύσεα μῆλα φυλάσσει.”

This means, in my own translation:

“And Keto, having mingled with Phorkys in love,

gave birth to her youngest, the formidable serpent, who, in the depths of the dark earth

at its great limits, guards the all-golden apples.”

From this passage, we can be certain that the idea of drakontes guarding treasure dates at least as far back as the early seventh century BCE.

ABOVE: Detail from Wikimedia Commons of a Roman mosaic dating to the third century CE, found in the town of Llíria, Valencia, now held in the National Archaeological Museum of Spain in Madrid, depicting Herakles trying to steal the golden apples from the Garden of the Hesperides, which are guarded by the drakōn Ladon

The Kolchian drakōn and the Golden Fleece

In the myth of Iason and the Argonauts, a drakōn is said to guard the Golden Fleece in the land of Kolchis. A very famous tondo from an Attic red-figure kylix painted by the vase-painter Douris at some point between c. 480 and c. 470 BCE depicts the Kolchian drakōn disgorging Iason as the goddess Athena watches. The drakōn itself is depicted as a giant, bearded serpent and the Golden Fleece is shown hanging on a tree directly behind it.

The myth of the Kolchian drakōn regurgitating Iason is only attested in the Douris kylix, but the myth of it guarding the Golden Fleece is retold in numerous ancient Greek literary sources, including the Hellenistic epic poem Argonautika, composed by the Greek poet Apollonios of Rhodes in the third century BCE.

Apollonios describes Iason’s lover, the sorceress Medeia, putting the drakōn to sleep with a magic spell in the Argonautika 4.139–166 as follows, as rendered in Richard Hunter’s prose translation, which I have edited slightly to make more closely reflect the Greek and have broken up into lines, trying to follow the Greek text as closely as possible:

“As when vast, murky clouds of smoke roll above a forest which is burning,

and a never-ending stream spirals upwards from the ground,

one quickly taking the place of another,

so then did that monster uncurl its vast coils

which were covered with hard, dry scales.

As it rolled towards them, the maiden [i.e., Medeia] fixed it in the eye

and called in a lovely voice upon Sleep, the helper, the highest of the gods,

to bewitch the beast; she invited too the queen,

the night-wanderer, the infernal, the kindly one, to grant success to their enterprise.

Behind her followed the son of Aison [i.e., Iason], terrified. Already under

the spell of the song the drakōn was relaxing the ridge

of its earth-born coils, and it stretched out its numberless spines,

as when a black wave rolls weak and noiseless on a gentle sea. Even so,

however, it lifted high its terrible head, seeking to enwrap

them both in its deadly jaws.

With a fresh-cut sprig of juniper

which had been dipped in a potion, Medeia sprinkled powerful drugs

over its eyes while she sang, and all around sleep was spread by the

overwhelming scent of the drug. Just where it was, its jaw dropped

to the earth and far into the distance its countless

spirals were stretched out through the thick wood.

Then Iason removed the Golden Fleece from the oak

at the maiden’s instruction. She stayed where she was,

rubbing the beast’s head with the drug, until Iason gave the order

to turn back towards the ship, and they left the deep-shaded grove of Ares.”

Due to its prominent appearance in the Argonautika, the Kolchian drakōn is possibly the most famous guardian drakōn in ancient Greek or Roman literature.

ABOVE: Tondo from an Attic red-figure kylix by the Douris Painter dating to between c. 480 and c. 470 BCE, discovered in Etruria, depicting the dragon of Kolchis regurgitating the hero Iason in front of the goddess Athena

Kadmos and the drakōn guarding the spring of Ares

Treasure, however, is not the only thing that drakontes guard in Greek myths. They are also commonly said to guard springs and bodies of water, especially those that are sacred to a particular deity. In one myth, for instance, a drakōn is said to have guarded the Ismenian spring near Thebes that is sacred to Ares.

The story goes that Zeus abducted and raped the Phoenician princess Europe and her brother, the Phoenician prince Kadmos, went out to search for her. Naturally, in the course of this search, he consulted the oracle of the god Apollon at Delphoi to ask the god where he might find his sister.

The Bibliotheke of Pseudo-Apollodoros, an ancient Greek mythographic work dating to the second century CE, summarizes the next part of the myth as follows at 3.4.21–23, as translated by Stephen M. Trzaskoma in the book Apollodorus’s Library and Hyginus’ Fabulae on page 47, with some edits of my own to make the text more closely reflect the Greek:

“The god told him not to pursue the matter of Europe, but to make a cow his guide and found a city wherever she collapsed from exhaustion. After receiving this oracle, he traveled through Phokis and then came across a cow among the herds of Pelagon and followed behind her. While she was passing through Boiotia, she lay down where the city of Thebes is now.”

“Wishing to sacrifice the cow to Athena, Kadmos sent some of his companions to get water from Ares’s Spring. Guarding the spring was a drakōn (some say it was Ares’s offspring), and it destroyed most of those who had been sent. Kadmos became angry and killed the drakōn.”

Thus, drakontes in Greek lore can also guard sacred springs, in addition to golden treasure.

ABOVE: Paestan red-figure kylix-krater dated to between c. 350 and c. 340 BCE depicting the hero Kadmos, the founder of Thebes, slaying the drakōn that guards the spring of Ares

Why do drakontes guard treasure?

Ancient Greek and Roman sources disagree about why drakontes seem to guard treasure so much. One ancient explanation holds that drakontes don’t actually care about treasure, but they guard it because the deities require them to. For instance, the Roman fabulist Gaius Iulius Phaedrus (lived c. 15 BCE – c. 50 CE) tells an Aisopic fable in his Fables 4.20 in which a fox digging its burrow accidentally stumbles upon a drakōn guarding treasure in an underground lair.

The fox immediately apologizes for disturbing the drakōn, saying that he is not interested in stealing the drakōn’s gold, since gold is of no use to him. Having made this apology, the fox asks the drakōn what he has to gain from guarding the treasure. The drakōn replies that he gains nothing, but he must guard the treasure anyway because Zeus has assigned the task to him. The conversation between the fox and the dragon reads as follows, in lines 8–13:

“‘Quem fructum capis

hoc ex labore, quodve tantum est praemium

ut careas somno et aevum in tenebris exigas?’

‘Nullum,’ inquit ille, ‘verum hoc ab summo mihi

Iove attributum est.’ ‘Ergo nec sumis tibi

nec ulli donas quicquam?’ ‘Sic fatis placet.’”

This means, in my own translation:

“‘What satisfaction do you receive

from this labor? What such reward is there

that you should go without sleep and endure your lifespan in the shadows?’

‘Nothing,’ he said, ‘Truly, this task is assigned to me

by highest Iove.’ ‘So you don’t take anything for yourself,

nor give anything to anyone?’ ‘So it is pleasing to the Fates.’”

Upon hearing this, the fox draws the moralizing conclusion that human misers are just like the drakōn, because they are both born under the curse of hostile deities.

ABOVE: Engraved illustration by Christopher Hagens for Phaedri Fabularum Libri Quinque (The Five Books of the Fables of Phaedrus), edited by Johannes Laurentius, published in 1667, illustrating the Aisopic fable of the fox and the drakōn

Another ancient interpretation, however, holds that drakontes have an innate love for golden treasure and that this is the reason why they guard it. For instance, the Greek sophist Philostratos the Elder (lived c. 190 – c. 230 CE) declares in his Imagines 2.17.6:

“Τὸν δὲ περίπλουν κολωνὸν τοῦτον οἰκεῖ δράκων πλούτου τινὸς οἶμαι φύλαξ, ὃς ὑπὸ τῇ γῇ κεῖται. τοῦτο γὰρ λέγεται τὸ θηρίον εὔνουν τε εἶναι τῷ χρυσῷ, καὶ ὅ τι ἴδῃ χρυσοῦν, ἀγαπᾶν καὶ θάλπειν· τό τοι κώδιον τὸ ἐν Κόλχοις καὶ τὰ τῶν Ἑσπερίδων μῆλα, ἐπειδὴ χρυσᾶ ἐφαίνοντο, διττὼ ἀύπνω ξυνεῖχον δράκοντε καὶ ἑαυτοῖν ἐποιοῦντο.”

“καὶ ὁ δράκων δὲ ὁ τῆς Ἀθηνᾶς ὁ ἔτι καὶ νῦν ἐν ἀκροπόλει οἰκῶν δοκεῖ μοι τὸν Ἀθηναίων ἀσπάσασθαι δῆμον ἐπὶ τῷ χρυσῷ, ὃν ἐκεῖνοι τέττιγας ταῖς κεφαλαῖς ἐποιοῦντο. ἐνταῦθα δὲ χρυσοῦς αὐτὸς ὁ δράκων· τὴν γὰρ κεφαλὴν τῆς χειᾶς ὑπερβάλλει δεδιὼς οἶμαι ὑπὲρ τοῦ κάτω πλούτου.”

This means, in my own translation:

“And, on this hill surrounded by the sea, abides a drakōn, who, I imagine, is the guardian of some wealth which is hidden beneath the earth. For this creature is said to be well-minded for gold and, whatever golden thing it sees, it loves it and warms it close. Thus, the fleece among the Kolchians and the apples of the Hesperides, since they appeared to be gold, two sleepless drakontes guarded and made their own.”

“And also the drakōn of Athena, which still even now abides on the Akropolis, seems to me to have welcomed the populace of the Athenians because of the gold which they make into cicadas for their heads. And, here, the drakōn himself is golden; for he thrusts his head out from his hole, dreading, I imagine, on behalf of the wealth below.”

Philostratos clearly regards drakontes as having an innate love for gold and treasure, much like the dragons of modern popular culture.

The dragon in Beowulf

The explanation that dragons guard treasure because they are obsessed with gold eventually found its way into the Old English epic poem Beowulf, which was composed in alliterative verse at some point between c. 700 and c. 1000 CE. In the poem, a treasure-loving dragon is guarding a hoard in its lair at Earnanæs. The poem describes the dragon’s innate instinct for hoarding golden treasure in lines 2275–2277, which read as follows in Old English:

“Hē gesēcean sceall

hord on hrūsan, þǣr hē hǣðen gold

warað wintrum frōd; ne byð him wihte ðȳ sēl.”

This means, in Seamus Heaney’s translation:

“He is driven to hunt out

hoards under ground, to guard heathen gold

through age-long vigils, though to little avail.”

After a slave breaks into the dragon’s lair and steals a jeweled cup, the dragon notices that the cup is missing and goes on a devastating rampage, in which he burns all the surrounding homes and farmland. This leads the hero Beowulf and his band of warriors to go to the dragon’s lair to slay it.

Beowulf tells his men to stay outside the lair while he goes inside to fight the dragon alone, but he soon finds that he has greatly underestimated the dragon’s prowess; it shatters his sword and mortally wounds him. All Beowulf’s men flee in terror into the woods, except for one loyal young man named Wiglaf, who comes to Beowulf’s aid. Together, the two men slay the dragon. Beowulf names Wiglaf as his heir and dies of his wounds soon afterward.

ABOVE: Illustration made by the English illustrator J. R. Skelton in 1906 showing Beowulf battling the dragon, as described in the Old English epic poem Beowulf

Fáfnir in the Vǫlsunga Saga

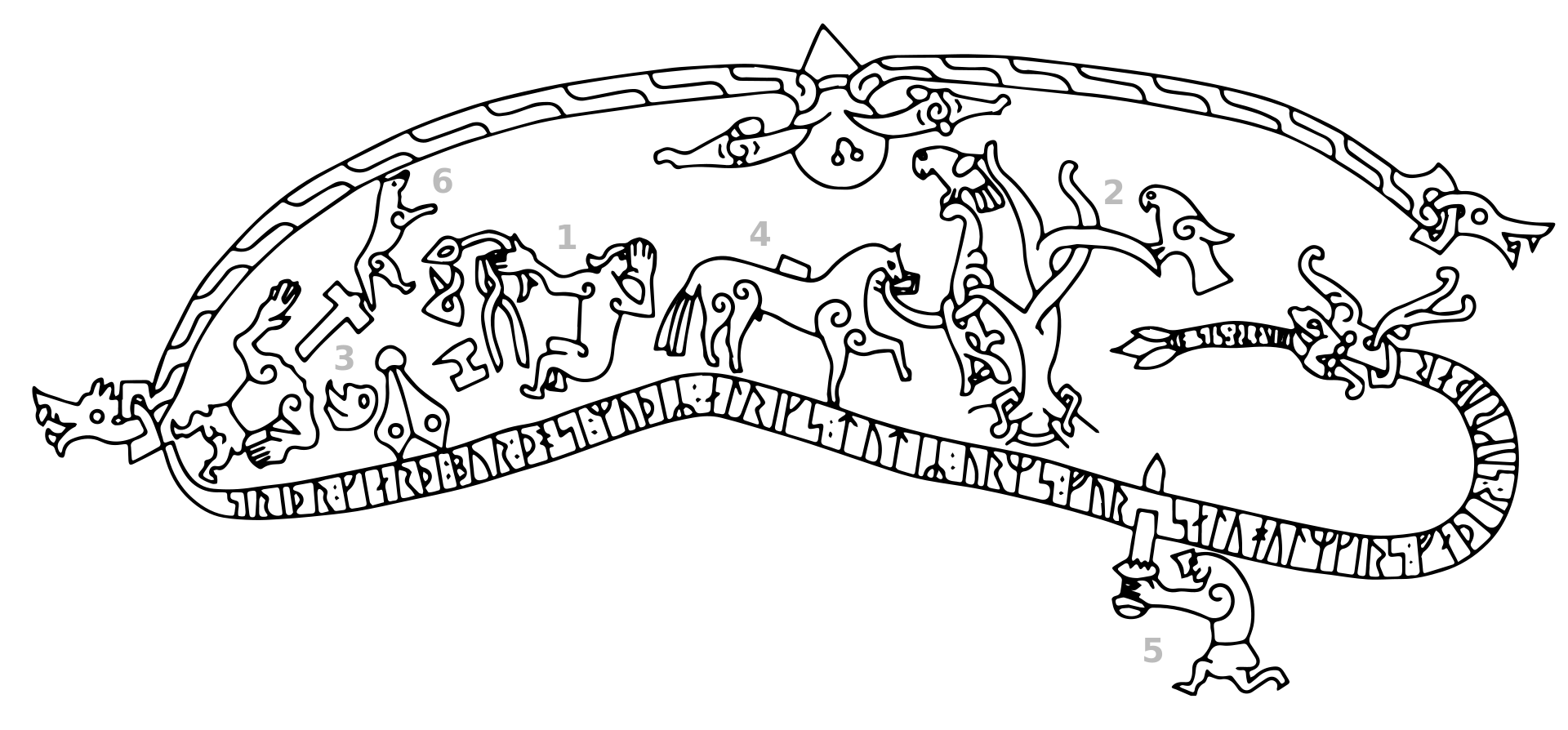

The idea that dragons are obsessed with hoarding gold also notably appears in the Germanic myth of Fáfnir. This myth was evidently already in circulation in Scandinavia by at least the eleventh century CE, as evidenced by the Ramsund carving in Södermanland, Sweden, which dates to around 1030 CE and depicts scenes from the myth of Fáfnir. The most famous version of the story, however, occurs in the Vǫlsunga Saga, a very long Icelandic poetic retelling in Old Norse of the history and deeds of the Vǫlsung clan that is thought to have been composed in the late thirteenth century CE.

In the saga, there is an extraordinarily wealthy dwarf named Hreiðmarr, who has three sons: Fáfnir, Ótr, and Reginn. Fáfnir is the largest of all the sons and the one who is most inclined toward violence. Ótr is skilled at fishing and can take the form of an otter. Reginn is a smith highly skilled in the art of working precious metals.

One day, while the gods Óðinn, Hœnir, and Loki are out fishing, they happen to capture Ótr while he is in the form of an otter. Not realizing that he is actually a dwarf and mistaking him for a real otter, they kill him, skin him, cook his flesh, and eat him. Then the gods come to Hreiðmarr’s home and proudly showed off Ótr’s pelt. Hreiðmarr, Reginn, and Fáfnir capture the gods and hold Óðinn and Hœnir for ransom, ordering Loki to go out, fill Ótr’s pelt with gold, and return the pelt to them as a ransom for Óðinn and Hœnir’s release.

Loki goes to the dwarf Andvari and coerces him into giving up his hoard of golden treasures to fill the pelt. At first, Andvari tries to keep the magic ring Andvaranaut, but Loki forces him to give it up, leading Andvari to curse the ring and the entire treasure, declaring that they will bring a terrible, early, and violent death to anyone who possesses them.

Having successfully wrested the gold from Andvari, Loki gives Ótr’s pelt filled with Andvari’s treasure to Hreiðmarr and the dwarf agrees to release Óðinn and Hœnir. Loki tries to warn Hreiðmarr that the treasure is cursed, but the dwarf, in his greed and lust for further riches, ignores his warning. Instead of sharing the treasure with his sons Reginn and Fáfnir, Hreiðmarr decides to keep all the treasure for himself. In response to this, Fáfnir murders his own father and steals all Andvari’s cursed treasure for himself.

Soon, Fáfnir becomes completely obsessed with the treasure and he goes out into the wilderness to hide with it so that no one will be able to take it from him. Overcome by his obsession and greed, he transforms into a dreki or dragon and, with his poisonous breath, he kills everything within a wide radius surrounding his lair.

ABOVE: Illustration from Wikimedia Commons showing the Ramsund carving dating to around 1030 CE, depicting scenes from the myth of Fáfnir, which is also told in the Vǫlsunga Saga

Meanwhile, Reginn adopts the hero Sigurðr as his son and tells him the story of how Fáfnir stole Andvari’s treasure. Sigurðr promises that he will slay Fáfnir if Reginn will forge him a sword that is mighty enough to accomplish the deed. Reginn forges a sword for Sigurðr, but the hero tests it by striking it against an anvil and it shatters. Reginn forges him another sword, but this one also shatters when Sigurðr tests it.

Finally, Sigurðr’s mother Hjǫrdís gives Reginn the broken halves of Sigurðr’s father’s sword Gram. Reginn uses the broken halves of the sword to reforge Gram and gives it to Sigurðr. This time, when Sigurðr strikes Gram against the anvil, he cuts the anvil in two.

After going on some other exploits, Sigurðr sets out to slay Fáfnir. He observes that the dragon routinely leaves his cave to go to a stream for water, so he digs a pit at a location between the cave and the stream. He hides in the pit to wait until Fáfnir comes along, then he kills the dragon by stabbing him in the underside from below as he crawls over the pit. As he lies dying, Fáfnir warns Sigurðr that his gold will bring about the hero’s untimely demise.

Reginn drinks Fáfnir’s blood and tells Sigurðr to cook his brother’s heart and let him eat it. Sigurðr cooks the heart, but he sticks his thumb into it and licks his thumb to test whether the heart is fully cooked. Suddenly, after tasting the heart, he finds that he has gained the ability to understand the language of the birds. He overhears a conversation of two birds talking about how Reginn is secretly plotting to murder him. Sigurðr therefore preemptively murders Reginn, eats the heart for himself, and takes as much of Fáfnir’s cursed treasure as he can carry, including the cursed ring Andvaranaut.

ABOVE: Detail from Wikimedia Commons showing part of the right portal plank of the Hylestad Stave Church in Setesdal district, Norway, dating to the late twelfth or early thirteenth century CE, depicting Sigurðr slaying the dragon Fáfnir

J. R. R. Tolkien’s Smaug

The English novelist J. R. R. Tolkien was a scholar of Old English literature who extensively studied Beowulf and was also closely familiar with the Vǫlsunga Saga. Between 1920 and 1926, Tolkien produced his own translation of Beowulf from Old English alliterative verse into Modern English prose. His son Christopher Tolkien subsequently edited this translation and published it in May 2014 through HarperCollins under the title Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary.

In 1925, Tolkien became the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at the University of Oxford and, in 1936, he delivered an acclaimed lecture titled “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” at the British Academy, which was subsequently published as a paper in the academic journal Proceedings of the British Academy later that year. This paper is now widely considered a foundational work in the modern academic study of Beowulf and one which fundamentally changed the scholarly understanding of the monsters in the poem, including the dragon, in particular.

ABOVE: Photograph of J. R. R. Tolkien, taken c. 1936, the year before The Hobbit was published, reproduced in the book The Inklings by Humphrey Carpenter, published in 1979, on page 70

Unsurprisingly, given his extensive study of Beowulf, Tolkien drew heavy inspiration from the dragon in Beowulf for the dragon Smaug in his children’s fantasy novel The Hobbit, which was first published in the U.K. in October 1937 through George Allen & Unwin.

The Hobbit became an immediate bestseller and critics almost universally lauded it as a masterpiece. The novel has never been out of print since its publication over eighty years ago. According to this article in USA Today, it has been translated into over fifty languages and is estimated to have sold over 100 million copies. It has spawned numerous adaptations, including a 1977 animated musical television special by Rankin/Bass and a three-part live-action film series directed by Peter Jackson, which was released between 2012 and 2014.

The Hobbit and its sequel The Lord of the Rings have fundamentally shaped the modern fantasy genre, possibly to a greater extent than any other books. As a result, the idea that dragons are obsessed with treasure has become the standard explanation for why they guard hoards of it in contemporary western popular culture, even though this is not the only explanation that existed in antiquity.

ABOVE: Illustration made by J. R. R. Tolkien himself in 1936 showing the dragon Smaug lying on a massive heap of golden and jeweled treasure

(NOTE: This post is adapted from an answer I originally wrote as a response to the question “When did the stereotype of gold loving dragons start, and why?” in r/AskHistorians.)

I wonder if the Douris kylix is based off a more humorous version of the slaying of the Colchian dragon. I can’t help but imagine a version of the myth where Jason tries to slay the dragon but get swallowed whole instead, and Athena (maybe answering a prayer from Jason to save him) forces the beast to vomit the hero out.

The Douris kylix unquestionably indicates that there was a version of the myth in antiquity in which, somehow or another, the drakōn swallows Iason and Athena rescues him by causing the drakōn to regurgitate him. Sadly, there is no way for us to know the full version of that myth, since it is not attested in any surviving written source.

I’m afraid I can’t see the image. Is it just me?

The image of the Douris kylix in the article above shows up perfectly well on my screen, even when I am logged out from WordPress. I’m not sure why you wouldn’t be able to see it.

I can see it now! 😅

Huh. That’s strange. I have no idea why you couldn’t see it before.

Hi Spencer,

Nice post, again…🙂

Knowing that archaeology of the past century and a bit has given us some clues as to the possible real root event of the creation of some myths, couldn’t we say that dragon stories were created by people of some local community or other as a way to scare “others” from taking their source of wealth, be this a technique of gold extraction from river beds (golden fleece) or a water source or other treasure/wealth…

We should remember that myths were created way back in the past, very long before there were writers to write them and copiers to copy them for other writers to be inspired to write more of them.

Being a fan of dragons in general, I really loved your article!

As someone who likes to read Old Norse literature in the original language, I would also add that Fáfnir is a prominent character in the Völsunga saga, a rather long saga describing the various exploits of the Volsung family, and also working as a sort of prose compendium of much mythological material, since the characters very often meet mythological characters who tell them their stories among which is Fáfnir. The terminology used to describe him is rather interesting: he is a ‘dreki’, which is apparently a kind of ‘ormr’. ‘Ormr’ is the native Old Norse word used to describe any reptile, and it’s also used to describe any native mythological reptile, such as Niðhöggr in the mythological poems such as the old Eddas. ‘Dreki’ is a very old borrowing from Latin ‘dracus’, which had become rather naturalized by that time. Still, the description of Fáfnir is clearly inspired by the Greco-roman literature, including the obsession with treasure. In the Völsunga saga, however, there is a twist in the story, since Fáfnir used to be a human, and instead became a dreki only when he stole a dwarf’s treasure out of greed. Therefore, in this story the greed itself is not just a characterstic of dragons, but also something which might cause someone to become a dragon. I believe C.S. Lewis borrowed this concept and utilized it in his ‘The Voyage 0f the Dawn-Treader’.

As a side-note/trivia, I’d add that ‘dreki’ also means ‘the dragon-shaped bow of a ship’ (also called drekahöfuð, ‘drake-head’), and metaphorically a ship itself.

I thought about talking about Fáfnir, but I knew that his story would require a whole section of its own and I ultimately decided that I didn’t want to take the extra time to write all that. Still, though, it seems like a striking omission, so I may go back and add something about him later.

(By the way, as a minor correction/sidenote, the Latin word you’re thinking of as the source for the Norse word dreki is actually draco; the word dracus does not exist in Latin.)

Lol, I have no idea why I messed up the Latin word 😛

It’s ok! We all do it sometimes! I know that I’ve definitely forgotten and messed up Latin words before.

I have now added a section to the article describing the myth of Fáfnir. It felt like too much of an omission for me to leave that story out.

There is a clever DVD called ‘The Last Dragon’ (beware martial arts films with the same name) made by the people who made the BBC’s ‘Walking with Dinosaurs’.

I need to pick up the Daniel Ogden book. I have seen bearded snakes on (photographs of) Greek coins (c. 360 BC and 350 BC to 300 BC) and did not make the connection that they were drakontes. For example, the head of Philoctetes is embossed with a drakon on the reverse of a couple of coins from Thessaly. I thought Philoctetes was bitten by a snake of normal size.

The book is unfortunately out of print, so, if you try to buy it online, it’ll be outrageously overpriced. I just looked at the Amazon page and it apparently costs over 200 USD for a used copy and over 220 USD for a new copy. You can find the book in other places, though. Most university libraries will probably have a copy that you can borrow for free and you might be able to find a used copy for a decent price somewhere. I am also aware that there are certain notorious shadow library internet sites out there where it is possible to download a complete PDF of the book for free—but, of course, I, as a good, law-abiding citizen who respects copyright laws, would certainly never advocate that anyone visit any of those sites.

Very interesting! I was expecting a word or two about Fáfnir too. His story was also a major influence in Tolkien, especially in one of the stories in The Silmarillion (namely, that of Túrin and the dragon Glaurung).