The Colossus of Rhodes was a gigantic bronze statue of the ancient Greek sun god Helios that stood on the Greek island of Rhodes during the third century BC. It was constructed between 292 and 280 BC in celebration of the fact that Rhodes had survived a prolonged, but unsuccessful siege in 305 BC by Demetrios I Poliorketes of Makedonia, the son of Antigonos I Monophthalmos.

Although the Colossus collapsed as the result of an earthquake only fifty-four years after it was built, it is still remembered today as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. There is, however, a pernicious modern misconception about the statue’s position and location. Many people believe that the Colossus originally straddled the harbor of Rhodes with one foot on either side, but, for reasons I shall soon explain, this notion is certainly erroneous.

Background

The Colossus of Rhodes was a sculpture of the ancient Greek sun god Helios, who was the patron god and protector of the island of Rhodes. It was designed by the Greek sculptor Chares of Lindos, who was a student of the famous sculptor Lysippos of Sikyon (lived c. 390 – c. 300 BC). Lysippos is known to have created colossal statues of Zeus and Herakles and it is likely that, before taking on the project of designing the Colossus, Chares already had experience designing and building colossal sculptures. The Colossus itself was probably made of bronze plates with stone-weighted iron interior framework.

The ancient Roman writer Pliny the Elder (lived 23 – 79 AD) records in Book Thirty-Four, Chapter 18 of his encyclopedic work Natural History, that the construction of the Colossus took twelve years to complete and that it cost no less than 300 talents. Pliny states that the Rhodians managed to raise this tremendous sum of money by melting down the large siege weapons used by the army of Demetrios I Poliorketes, which had been abandoned on Rhodes when the siege had ended.

Most ancient writers seem to agree that the Colossus of Rhodes stood at around seventy cubits high when it was erect. This is the statistic given by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, as well as the statistic given by the author of an anonymous poem quoted by the Greek geographer Strabon of Amaseia (lived c. 63 BC – c. 24 AD) in Book Fourteen, Chapter 2, Section 5 of his Geographika and by the late fourth-or-early-fifth-century AD Greek writer Philon of Byzantion in Chapter 4 of his treatise On the Seven Wonders.

Although this statistic is probably a rough estimate and not an exact measurement, it can be taken as a general indicator of about how tall the statue probably was. If the Colossus of Rhodes was really seventy cubits tall, that would mean that it was somewhere around thirty-two meters (105 feet) tall. For comparison, the height of the Statue of Liberty from the statue’s feet to the top of her torch is forty-six meters (152 feet). This would make the Colossus of Rhodes possibly the tallest known statue from antiquity. If it were still standing today, modern people would probably still be impressed by it.

Unfortunately, the Colossus of Rhodes only stood for about fifty-four years before it collapsed in 226 BC during a major earthquake. It lay broken on the ground for centuries afterwards. Indeed, it spent more time lying broken on the ground than it did actually standing upright. Nonetheless, people still came to Rhodes to see the remains of the statue. Even in its ruined state, the Colossus was still a true Wonder of the World. Pliny the Elder, who probably saw the ruins of the statue firsthand, tells us, as translated by John Bostock:

“Few men can clasp the thumb in their arms, and its fingers are larger than most statues. Where the limbs are broken asunder, vast caverns are seen yawning in the interior. Within it, too, are to be seen large masses of rock, by the weight of which the artist steadied it while erecting it.”

Eventually, in 653 AD, what remained of the Colossus was reportedly carted away and melted down by Arab conquerors under Caliph Muawiyah I to make bronze weapons and luxury items. You can recoil in disgust at this all you want, but, unfortunately, as tragic as this may seem, the melting down of old sculptures for raw materials was actually a fairly common practice in the ancient world.

When people in ancient times needed raw metals or quick cash, it was not uncommon for them to melt down old sculptures and other decorations made of precious metals. For instance, towards the end of the Peloponnesian War (431 – 404 BC), the Athenians raided their own Akropolis and used the gold and silver decorations to fund the war effort. Similarly, during the Third Sacred War (356 – 346 BC), the Phokians seized the Temple of Apollon at Delphoi and used the treasures that had been dedicated there to fund an army of mercenaries.

In fact, the prevalence of people melting down old sculptures in ancient times is a major reason why they are more surviving marble sculptures from antiquity than bronze sculptures, even though many sculptures were actually made of bronze. Quite simply, many of the bronze sculptures were melted down to make things; whereas the marble sculptures could not be melted down and were therefore more likely to survive. The Colossus of Rhodes is just one of many ancient bronze sculptures that were melted down for raw materials.

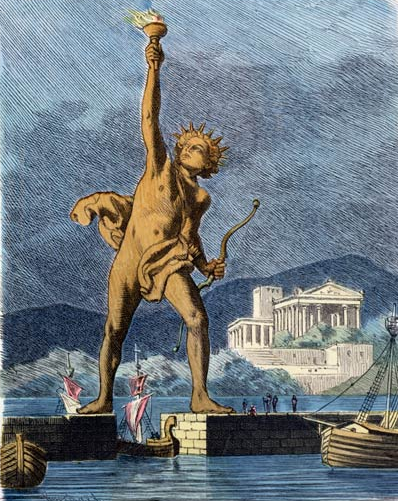

ABOVE: Imaginative illustration of the Colossus of Rhodes by the sixteenth-century Dutch artist Maarten van Heemskerck erroneously showing it straddling the harbor of Rhodes.

The modern image of the harbor-straddling Colossus

The image of the Colossus of Rhodes straddling the Rhodian harbor with ships passing underneath it is thoroughly ingrained in modern culture, but it is not an image that existed in antiquity at all. It is instead an image that first arose during the Late Middle Ages (c. 1250 – c. 1450 AD). The earliest known reference to it comes from an account written by an Italian who visited Rhodes in 1395 and heard a local tradition that the Colossus’s right foot had once stood on the site of a small round church known as the “Church of St. John of the Colossus.”

This image of the Colossus grew in popularity over the course of the following centuries. It was eventually immortalized by a famous simile used by the great English playwright William Shakespeare (lived 1564 – 1616) in Act I, Scene II of his great tragedy Julius Caesar, which was written in around 1599. In that scene, the character Cassius speaks these famous lines, describing Julius Caesar:

“Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world

Like a Colossus, and we petty men

Walk under his huge legs and peep about

To find ourselves dishonourable graves.”

The image of the Colossus of Rhodes straddling the Rhodian harbor was later incorporated into the sonnet “The New Colossus,” written in 1883 by the American poet Emma Lazarus (lived 1849 – 1887). This poem is inscribed on a bronze plaque housed inside the giant pedestal on which the Statue of Liberty stands. Many people in the United States know its final six lines by heart. Here is the full text of the poem:

“Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

‘Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!’ cries she

With silent lips. ‘Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!'”

ABOVE: Photograph of the bronze plaque with the full text of the poem “The New Colossus” housed inside the pedestal underneath the Statue of Liberty

The image of the Colossus of Rhodes straddling the Rhodian harbor has also influenced modern fantasy literature. A fictional statue clearly inspired by the legendary harbor-straddling Colossus appears in the popular book series A Song of Ice and Fire, written by the American author George R. R. Martin, as well in its television adaptation, Game of Thrones.

The statue in both the book series and the television series is called “the Titan of Braavos,” and it is described as straddling the harbor of the fictional city of Braavos with one foot on either side—just like how the Colossus of Rhodes is so often wrongly envisioned. The Titan of Braavos, however, unlike the Colossus of Rhodes, is described as a warrior wielding a shield and a broken sword and it lets out a terrible roar whenever a ship is approaching.

ABOVE: Shot of the Titan of Braavos as portrayed in the television show Game of Thrones, based on the book series A Song of Ice and Fire by George R. R. Martin

The image of the harbor-straddling Colossus does not just appear in poetry and fiction, though. A few years ago, a group of Greek architects and engineers came up with a rather hair-brained scheme to rebuild the Colossus of Rhodes. They established what they were calling the “Colossus of Rhodes Project,” which received a great deal of media coverage.

The project came up with some elaborate designs for what the new Colossus of Rhodes would look like. These designs, of course, entailed making the Colossus straddle a portion of the Rhodian harbor. Needless to say, nothing has come of these fanciful plans and I doubt anything ever will, but this illustrates just how ingrained the image of the Colossus straddling the harbor of Rhodes seems to be.

ABOVE: Image by Ari A. Palla of what the new Colossus of Rhodes planned by the Colossus of Rhodes Project would have looked like

Why the Colossus could not have been straddling the harbor

Even though the image of the Colossus straddling the Rhodian harbor remains eternally popular, there is no way the real Colossus of Rhodes could have actually been built in such a position. The first reason why the Colossus was definitely not straddling the harbor is because there is not a single ancient source that ever claims that it was. The earliest sources claiming that it stood like this are from the Late Middle Ages and were written by authors who had never actually seen the Colossus. On this basis alone we can conclude that the Colossus was probably not straddling the harbor.

If the complete lack of ancient evidence is not enough to convince you, however, there is also compelling evidence that the Colossus was not straddling the harbor. The first and most obvious piece of evidence is the fact that building a bronze statue large enough to have straddled the harbor would have been technologically impossible given the tools and materials available at the time. The harbor of Rhodes today is roughly 150 meters wide, which is nearly the width of an American football field. In antiquity, the harbor may have been even wider.

In order for the Colossus of Rhodes to have straddled that distance and still looked vaguely proportionally correct, it would have had to have been something like 500 meters tall, which is taller than the Willis Tower in Chicago. No one has ever built a statue that tall. The tallest statue on earth today is the Statue of Unity at Kevadiya in the Indian state of Gujarat. It stands at a height of only 182 meters.

Quite simply, it would have been impossible using the technology available to the Rhodians in the third century BC for any statue to have been built large enough for it to have straddled the harbor of Rhodes. Even today, with all our modern building technology, I am still not sure it would be possible. Those plans the Colossus of Rhodes Project came up with are simply fantastical and building a real statue like that would be wildly impractical to say the least.

Even if the ancient Rhodians somehow possessed the technology to build such a massive statue, the ancient sources usually claim that the Colossus was only seventy cubits tall. At that height, the feet of the Colossus of Rhodes could have been maybe eight meters apart at the most—certainly not 150 meters apart.

ABOVE: Photograph of the Willis Tower in Chicago. In order for the Colossus of Rhodes to have straddled the Rhodian harbor, it would have had to have been at least the height of the Willis Tower, perhaps taller. No one has ever built a statue that tall.

Aside from the fact that no ancient writer ever claims that the Colossus of Rhodes straddled the harbor of Rhodes and the fact that building a statue tall enough to do such a thing would have been impossible in the third century BC, it is clear that the Rhodians would never have wanted to build the statue in such a bizarre and awkward position anyways.

The Colossus of Rhodes was supposed to be a statue of the sun god to honor him for having saved the Rhodians from the siege by Demetrios I Poliorketes. Do you really think someone would have wanted to build a statue of the sun god in a such a ridiculous, awkward, and undignified position as straddling the harbor?

Besides, the statue was probably naked and, if it had been straddling the harbor, any ships coming into the harbor would have needed to pass directly under the statue’s crotch. Just imagine how undignified the god would seem if anyone coming into the harbor could see his bare genitals dangling down over their heads. I mean, come on. Would you want to put your god in a position like that?

ABOVE: Painting from 1886 by Ferdinand Knab depicting the Colossus of Rhodes straddling the harbor with a ship passing underneath it. Just think what an undignified position this would be for a statue of a god.

Finally, we know that, when the Colossus collapsed, it collapsed on land, where people still visited what remained of it for centuries thereafter. If the Colossus had stood over the harbor, then, when it collapsed, it would have fallen into the harbor and sunk to the bottom where no one would have been able to see it. Therefore, if the Colossus had somehow been built over the harbor, we would certainly not have Pliny’s detailed description of it lying broken on the ground and people trying to wrap their arms around its thumb.

When you look at all the evidence, it soon becomes clear that the portrayal of the Colossus straddling the harbor of Rhodes is simply downright impossible and frankly rather ridiculous. No ancient writer ever describes the Colossus as having stood over the harbor; it would have been impossible for the Rhodians to have built it like that; it makes no sense why the Rhodians would have even wanted to build the statue like that; and, finally, the image of the Colossus straddling the harbor is totally incompatible with the description of it having collapsed on the land.

ABOVE: Modern photograph retrieved from Wikimedia Commons showing what the old harbor of Rhodes looks like today

Was it even near the harbor of Rhodes at all?

We actually do not have any definitive evidence to indicate that the Colossus of Rhodes stood in the harbor of Rhodes at all. The idea that it stood in the harbor is nothing more than a modern assumption without any ancient sources to support it. Neither Pliny the Elder nor any other ancient writer ever describes the statue’s precise location. All we know is that the Colossus was on the island of Rhodes in a very visible, public place and that, when it collapsed, it fell on land.

The statue may have stood on one side of the harbor of Rhodes, atop the Rhodian Akropolis, or at some other prominent location. Wherever it stood, it probably stood atop some kind of pedestal. This pedestal probably bore an inscription that has been preserved through quotation in the Greek Anthology dedicating the sculpture to the sun god Helios.

ABOVE: Illustration from 1880 depicting how the artist imagined the Colossus of Rhodes might have looked. This illustration accurately depicts the Colossus as having both feet on the same pedestal and not holding a torch. The location shown here is probably inaccurate, however.

What did the Colossus really look like?

Although we do not know exactly where the Colossus of Rhodes stood, we do have a pretty good impression of what its face would have looked like. The god Helios is frequently portrayed on ancient Rhodian coinage and his portrayal as the Colossus would have probably looked very much like how he is portrayed on contemporary Rhodian coins. On Rhodian coins, Helios usually has long, flowing hair and rays of light emanating from his head. It is likely that the Colossus would have looked the same.

ABOVE: Rhodian silver tetradrachm dating to c. 230 – c. 205 BC depicting the head of Helios on the obverse and a rose on the reverse. Here Helios is shown with long, flowing hair and rays of light radiating from his head.

Although the Colossus of Rhodes is often portrayed today holding a torch, there are no ancient sources that mention anything at all about the statue having held a torch, nor do we have any good evidence that it was holding one. The portrayal of the statue as holding a torch seems to originate from a misreading of the surviving epitaph that is believed to have been inscribed on the statue’s pedestal. This epitaph mentions that, with the building of the Colossus, the Rhodians were kindling the torch of freedom. Someone at some point apparently mistook this to mean that the statue itself was holding a torch.

Conclusion

The Colossus of Rhodes stood at some prominent location on the island of Rhodes with both feet together on the same pedestal. The widespread image of the Colossus straddling the harbor of Rhodes is nothing but pure fantasy with no basis whatsoever in any ancient sources. We do not know if the statue really stood anywhere near the harbor; for all we know, it could have been miles away from the harbor.

The Colossus was probably not holding a torch as it is often portrayed either, since the notion that it was holding a torch seems to have originated from a naïve misreading of the poem believed to have been the statue’s epitaph. Even though it spent more time lying broken on the ground than actually standing, the Colossus of Rhodes was undoubtedly one of the tallest statues ever built during antiquity and a true Wonder of the Ancient World.

Thanks for this. I’ve been fascinated by the Colossus since I was a child, and read quite a bit about it over the years (well, what little is known) but learned a few new things here. For example, I never realized it was not even necessarily near the harbor. The fact that we know it fell on land, and not water, makes a lot more sense this way.

BTW, I discovered your site a few months back and have been a devoted reader ever since. While I was a history major in college (many years ago), and keep up with a steady supply of “dad history” these days, my knowledge of classical history is patchy, so I have really enjoyed reading your blog; you make lots of complex topics accessible and interesting for me. (It also helps me feel a tiny bit more connected to my heritage – I was raised as “Greek” in the US, although I have only a single Greek grandparent). Anyway, thank you!

You’re absolutely welcome! I really appreciate the positive feedback. It is always great to hear that people are enjoying reading my articles. I’ve found that, at least here in the United States, most people don’t know very much about ancient history. Even most history buffs seem to generally focus on modern American history. I’ve just been doing my part to help educate people about the ancient past.