Most high school students in the United States read at least one work of ancient Greek drama at some point in one of their English classes and, when they do, they are usually taught lots of Greek words like tragedy, comedy, hubris, and hamartia. Unfortunately, a lot of these terms have been egregiously misunderstood over the years and do not actually mean what many English teachers—and consequently English students—think they mean.

Not only are Greek terms often misunderstood; so are the Greek plays themselves. One of the most commonly taught Greek plays is Oidipous Tyrannos (Oedipus Tyrannus). Partly on account of its popularity, this particular play has been widely misunderstood by English teachers and students alike.

Some of these misunderstandings can even prevent students from fully appreciating Greek drama, so I think it is worthwhile to address them here. Below I address some of the most widespread misconceptions about Greek drama.

Misconception #1: All Greek tragedies have a “tragic” ending, in which the protagonist suffers some kind of downfall.

High school students are usually taught that Greek tragedy is defined as a genre by the fact that the protagonist always suffers some kind of dramatic downfall near the end of the play. This idea is reinforced by the use of the term “tragic ending” to refer to a story that ends badly for the protagonist.

This is not a very accurate way of describing ancient Greek tragedy, however. It’s certainly true that the protagonist of a Greek tragedy often dies or suffers some kind of dramatic downfall at the end of the play, but this is not a defining characteristic of the tragic genre. In fact, many of our surviving Greek tragedies do not end with the protagonist dying or suffering any kind of horrible fate or downfall at all.

Take, for instance, the tragedy Alkestis by Euripides, which was originally performed in Athens at the City Dionysia in 438 BC. This play takes everything we would normally consider a “tragedy” and flips it on its head. Instead of ending with the main character dying, the play begins with Alkestis’s death and ends with the hero Herakles wrestling Thanatos, the divine personification of death, for her soul and bringing her back to life.

In the final scene of the play, Herakles presents the resurrected Alkestis to her husband, King Admetos of Pherai. There is debate among scholars over whether this is supposed to be a happy ending, since Alkestis is unable to speak in the final scene, and it is therefore it unclear whether she actually wanted to be brought back to life. In any case, there can be little doubt that the ending of Alkestis is hardly what anyone thinks of when they hear the phrase “tragic ending.”

ABOVE: Hercules Wrestling with Death over the Body of Alcestis, painted by the English Academic painter Frederic Leighton

Euripides liked to deliberately flaut the conventions of the tragic genre, but he was certainly not the only one who wrote tragedies with endings that we would not consider particularly “tragic.” Another example of this is Philoktetes, a tragedy originally performed at the City Dionysia in 409 BC and written by none other than the Athenian playwright Sophokles, the same one who wrote Oidipous Tyrannos and Antigone.

Philoktetes is about as solidly a tragedy as you can get, but yet, contrary to the modern popular supposition that all tragedies are supposed to end with the protagonist dying or suffering some kind of other horrible downfall, Philoktetes does not include a single character death.

The play is about Philoktetes, a master archer who has the bow and arrows of Herakles. He was bitten on the foot by a serpent while the Greek were sailing for Troy. For unknown reasons, his wounded foot would not heal and it stunk horribly, so the Greeks abandoned him on the island of Lemnos. Then, nearly ten years later, in the last year of the Trojan War, the Greeks learned of a prophecy that they could not defeat the Trojans without the bow of Herakles, so they sent Odysseus and Achilles’s son Neoptolemos to Lemnos to convince Philoktetes to give them the bow.

The play focuses on Odysseus and Neoptolemos’s efforts to convince Philoktetes to cooperate with them. Philoktetes initially refuses, but, then, at the end of the play, the divine Herakles appears to him and tells him that, if he goes to Troy with Odysseus and Neoptolemos, then his foot will be healed and the Greeks will win the Trojan War. Finally, Philoktetes agrees. Thus, like Alkestis, Philoktetes actually has something more closely resembling a happy ending than a conventionally “tragic” one.

ABOVE: Philoctetes on the Island of Lemnos, painted in 1798 by the French Neoclassical painter Guillaume Guillon-Lethière

Now, I will admit that Alkestis and Philoktetes are not exactly the most famous of all ancient Greek tragedies; I doubt either of them has ever been taught in a high school English class. There is, however, at least one very famous tragedy that does not have an ending that we would normally consider “tragic.” I’m talking about The Eumenides, the final play of Aischylos’s Oresteia trilogy, which also includes Agamemnon and The Libation-Bearers. The Oresteia is the only complete trilogy of ancient Greek tragedies and the plays that make it up are among the most famous and widely studied.

The Eumenides is about Orestes, the son of Agamemnon and Klytaimnestra. In Agamemnon, the first play in the trilogy, Klytaimnestra murders her husband Agamemnon after he returns from Troy, along with the Trojan princess Kassandra, whom he has brought home as a slave. In the second play in the trilogy, The Libation Bearers, Orestes murders Klytaimnestra and her lover Aigisthos. At the beginning of The Eumenides, Orestes is relentlessly pursued by the Erinyes, a group of terrifying, hideous, chthonic goddesses whose duty is to punish those who have murdered their own blood relatives.

The play does not end with the Erinyes viciously tearing Orestes to shreds as punishment for his crimes, though; instead, it ends with the gods Apollon and Athena setting up a trial for him with the first jury. Ultimately, the jury is split evenly and Athena herself casts the deciding vote to acquit Orestes. The Erinyes are enraged, but Athena placates them. They henceforth become the Eumenides, a group of goddesses who serve as protectresses of the city of Athens. Their new name means “the Kindly Ones.” Thus, despite all the people who are killed throughout the Oresteia, The Eumenides actually concludes the trilogy with a relatively happy-ish ending.

ABOVE: Orestes Pursued by the Furies, painted in 1862 by the French Academic painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau

Misconception #2: All Greek tragedies have a uniformly serious tone.

Greek tragedy is not strictly defined by its “serious tone” either. While tragedies do generally tend to be serious in tone, it is not uncommon for them to contain humorous episodes and exchanges. For instance, there is at least one example of a scene in a tragedy that outright parodies a scene in another tragedy.

In Aischylos’s tragedy The Libation Bearers, there is a highly implausible scene in which the heroine Elektra recognizes a lock of hair left at her father’s tomb and a footprint nearby as belonging to her brother Orestes, who has been living in exile for many years. Later, when she encounters Orestes, she recognizes him because he is wearing a piece of clothing she made for him years previously when he was but a child.

Euripides evidently had nothing but contempt for this scene, because he unmistakably satirizes it in his own tragedy Elektra. The resulting scene is absolutely dripping with irony. In Euripides’s rendition of the scene, an old man (an obvious stand-in for Aischylos) finds a lock of Orestes’s hair at Agamemnon’s tomb and presents it to Elektra, saying that he thinks it might be Orestes’s. Here is the conversation, as translated by Emily Wilson in her translation of Euripides’s Elektra:

Old Man: “…Look at this hair, compare it with your own:

See if your color matches with the lock.

It’s natural, those who share one father’s blood

are physically alike in many ways.”Elektra: “Gosh, what a silly thing to say, old man!

You think my hero brother would sneak here

in secret? He’s not frightened of Aigisthos!

And how can you expect the locks to match?

Blue-blooded men teach roughness to their hair

by wrestling. Female hair’s acquired by combing!

In any case, people who aren’t related

often have matching hair color. You know that.”Old Man: “Then step into the marks his boots have made;

see if your foot will match its size, my child.”Elektra: “But how could there be any print at all

on stony ground? Or even if there were,

the man and woman’s feet won’t match together

even for siblings! Male is more than female.”Old Man: “Well, if your brother has come to this land,

wouldn’t you recognize the cloth you wove,

in which I wrapped him when I saved his life?”Elektra: “But I was still a child when he escaped.

I wasn’t weaving. And, even if I had,

how could he still be wearing his baby clothes?

Just use your head! His clothes grew, with his body.”

The characters in the play have no idea that everything the old man is describing here is taken straight out of Aischylos’s Libation Bearers, but the audience certainly knew it. This whole scene is Euripides using dramatic irony to make fun of Aischylos.

ABOVE: Illustration by Alfred Church from the 1897 book Stories from the Greek Tragedians showing Elektra and Orestes at the tomb of Agamemnon

Euripides was even willing to incorporate some of the crassest humor imaginable into his darkest tragedies. His play The Trojan Women, a tragedy about the royal women of Troy whose husbands and male relatives have all been killed, whose home city has been razed to the ground, and who are being taken as sex slaves by the Greek commanders, was first performed in Athens in 415 BC at the City Dionysia. It is arguably his darkest play.

Despite this, in lines 1049 through 1050 of it, this exchange takes place between Hekabe, the now-enslaved wife of the dead King Priamos of Troy, and Menelaos, the king of Sparta and husband of Helene:

Ἑκάβη: μή νυν νεὼς σοὶ ταὐτὸν ἐσβήτω σκάφος.

Μενέλαος: τί δ᾿ ἔστι; μεῖζον βρῖθος ἢ πάροιθ᾿ ἔχει;

Hekabe: In that case, Helene should not board the same ship as you.

Menelaos: Why is that? Has she put on weight since the last time she sailed?

Oh yes, you read that correctly. Euripides literally just told a fat joke in the middle of The Trojan Women!

If it is not a “tragic ending” or even a consistently serious tone that makes a tragedy a tragedy, then what exactly does make a tragedy a tragedy? The answer is that ancient Greek tragedies are defined not by plot or tone, but rather by the characters they focus on. Greek tragedies are always about important, high-status individuals such as kings, heroes, deities, and other mythological figures; they are never about ordinary Athenians.

With one singular exception, all surviving ancient Greek tragedies are set in the distant, mythological past. This setting enabled tragic playwrights to criticize problems in contemporary society without making people feel like they themselves were being attacked. For instance, Euripides’s Trojan Women is widely believed to be a deliberate polemic against the Athenians’ brutal mistreatment of the Melians after the Siege of Melos in 416 BC.

The sole surviving exception to this rule that tragedies were always set in the distant, mythological past is the play The Persians by Aischylos, which was performed in 472 BC and is about the Persians’ defeat by the Greeks in the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC from the perspective of Atossa, the Queen Mother of the Persian Empire. We might, in a sense, call The Persians the “exception that proves the rule,” because it is the only surviving tragedy set in what was at the time the recent past, but yet it is still not about ordinary Athenians.

ABOVE: The Ghost of Darius Appearing to Atossa, drawn by George Romney, depicting a scene from Aischylos’s Persians

Misconception #3: The comedies of Aristophanes represent what “ancient Greek comedy” was always like throughout its history.

While tragedies were plays about gods, heroes, kings, and legendary figures, plays about ordinary Athenians exclusively belonged to the genre of comedy. Ancient Greek comedy certainly falls under the definition of what we today would consider “comedy.” Nonetheless, ancient Greek comedy changed drastically over the course of its history and there are actually two distinct eras of Greek comedy that are generally recognized by scholars who study the subject: “Old” Comedy and “New” Comedy.

Old Comedy, as the name implies, came before New Comedy. The main representative of the genre of Old Comedy is the Athenian playwright Aristophanes (lived c. 446 – c. 386 BC). Of Aristophanes’s approximately forty plays that he wrote over the course of his life, only eleven have survived to the present day complete, while the others have survived only in fragmentary form or not at all. He is the only playwright of Old Comedy for whom any plays have survived to the present day in their complete form.

Old Comedy and the plays of Aristophanes are characterized by a number of features:

- Their ribaldry. Aristophanes’s plays are filled with all kinds of dirty jokes, including sex jokes and bathroom humor. The characters in Old Comedy, for instance, wore enormous fake phalli (i.e. erect penises), which hung between their legs for comedic effect.

- The chorus. In the comedies of Aristophanes, the chorus plays a major role in the action.

- Political and social satire. Aristophanes’s plays routinely make fun of real people who were well known in Athens during the time period. For instance, he makes fun of the warmongering demagogue Kleon in many of his plays, but especially in The Acharnians (425 BC), The Knights (424 BC), and The Wasps (422 BC). In The Clouds (423 BC), Aristophanes makes fun of Sokrates and other intellectuals of the period.

- Comic absurdity. All of Aristophanes’s plays also feature comic absurdity as a prominent element. For instance, in Peace (421 BC), the protagonist Trygaios flies to Mount Olympos on the back of a giant dung beetle. In The Birds (414 BC), the protagonists Peisthetairos and Euelpides found a city in the clouds with the birds called Nephelokokkygia (literally translated, “Cloudcuckooland”). In Lysistrata (411 BC), the women of Athens and Sparta organize a sex strike to end the Peloponnesian War.

Aristophanes’s last surviving play, Wealth (388 BC), represents an interesting transitional phase from Old Comedy into the New Comedy which dominated from the mid-fourth century BC onwards. Wealth has sometimes been considered the only surviving example of “Middle Comedy.”

ABOVE: Photograph from the Ancient History Encyclopedia of an ancient Greek marble herma of the comic playwright Aristophanes. The portrayal shown here is probably imaginative, since Aristophanes’s own plays suggest that he was prematurely bald.

New Comedy is best represented by the works of the Athenian playwright Menandros (lived c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC), for whom two plays—The Grumpy Old Man and The Girl from Samos—have survived nearly complete, along with a large number of plays which have survived in significant portions. He is the only playwright of New Comedy for whom any plays have survived to the present day in their nearly complete form.

Menandros’s New Comedy is a far cry from Aristophanes’s Old Comedy. The ribaldry is toned way down. The chorus has been reduced to nonexistent. Political satire and comic absurdity of any kind are both virtually absent. Instead, the humor relies heavily on stereotypes, stock characters, situations, and dramatic irony. The genre is less much more refined. Likewise, while Old Comedy made use of deliberately farcical story lines and conflicts that are resolved early in the production in a humorous anti-climax, in the New Comedy, the plots are often very elaborate.

To draw some modern comparisons, the Old Comedy of Aristophanes was a bit like Saturday Night Live or Monty Python: full of a blend of crude humor, comedic absurdity, and political satire. New Comedy, by contrast, was a bit like a modern sitcom: generally much “cleaner,” but heavily reliant on stereotypes, situations, and dramatic irony.

This is not to say that New Comedy was better than Old Comedy. Neither era was inherently “better” than the other; they are just stylistically different from each other. Some people will prefer Old Comedy over New Comedy; whereas others will prefer New Comedy over Old Comedy. They appeal to different audiences. Nonetheless, the fact that Greek comedy changed greatly over time and that New Comedy is very different from Old Comedy is often left out when English classes study, say, Aristophanes’s Lysistrata.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of an ancient Roman marble copy of a Greek bust of Menandros, originally dating to around the time when he was actually alive

Misconception #4: The word hubris means “excessive pride.”

The word hubris comes from the Ancient Greek word ὕβρις (hýbris). It is usually defined in English as “excessive pride” and this is what most high school literature classes teach that it means. In reality, however, this is not actually what it means. Pride is a feeling; hubris is a characteristic of an action. It is used to describe something you do, something you act out, not something you simply feel. The word hubris is best defined as “extreme and unwarranted insolence, aggression, or violence characteristic of an act that violates or implies intention to violate the natural order of the cosmos as ordained by Zeus and the other gods.”

The classic example of an act of hubris is the story of how the hero Bellerophon tried to fly up to Mount Olympos on the back of the winged horse Pegasos, presumably to proclaim himself a god. Then Zeus sent a gadfly to sting Pegasos, causing him to buck Bellerophon off his back. Bellerophon fell into a thorn bush and it gouged out both his eyes, leaving him permanently blind. Then he lived out the rest of his miserable days on the Fields of Aleion.

Obviously, this act of trying to fly up to Mount Olympos is motivated by excessive pride, but that is not what matters for making it an act of hubris. What makes it an act of hubris is that it is an act of aggression against the gods—indeed, the ultimate act of aggression—and it violates the natural order of the universe.

For the ancient Greeks, it was very important to remember that a human being is not a god. (That is probably what the Delphic Maxim γνῶθι σεαυτόν, or “Know thyself,” is about, by the way.) For a human being to try to ascend to Olympos is the ultimate attempt to violate of the natural order.

ABOVE: Attic red-figure epinetron, dating to c. 425 – c. 420 BC, depicting Bellerophon on the back of Pegasos slaying the Chimera

But this is not the only way something can be considered an act of hubris. Engaging in acts of wanton violence against other people is also engaging in acts of hubris. Let us say you just waltz into Thebes and stab some random guy you run into on the street; that is an act of hubris, because it is an act of insolence, aggression, and violence that goes against the natural order, which holds that you are not supposed to just randomly stab people for no reason. Here, your act of stabbing the guy may not be motivated by pride at all, but it is still hubris.

I think the reason why people keep misinterpreting hubris as “excessive pride” is because today we generally tend to think a lot about the feelings that motivate a person to do something and their psychology, but the ancient Greeks were more interested in what a person actually did. Why they did it was not as important. Of course, part of the reason may also come from the misinterpretation of this quote from Aristotle’s Rhetoric:

“Hubris consists in doing and saying things that cause shame to the victim… simply for the pleasure of it. Retaliation is not hubris, but revenge… Young men and the rich are hubristic because they think they are better than other people.”

According to Aristotle, then, hubris is a form of sadistic cruelty most often engaged in by people who think they are better than everyone else. My guess is that people at some point read this passage and, for some reason, mistook Aristotle’s explanation of why people commit acts of hubris for the definition of hubris itself.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of a Roman marble copy of a bust of the Greek philosopher Aristotle by the sculptor Lysippos, dating to around 330 BC

Misconception #5: The word hamartia refers to a “tragic flaw” in the protagonist’s personal character that leads to his ultimate downfall.

The word hamartia comes from the Ancient Greek noun ἁμαρτία (hamartía), which, in turn, comes from the Ancient Greek verb ἁμαρτάνειν (hamartánein), meaning “to miss the mark” or “to go off course.” For over a century, the word hamartia has been commonly interpreted in English as referring to a “tragic flaw” in the protagonist’s personal character that leads to his ultimate downfall.

It is now generally agreed among scholars, however, that this is an egregious misinterpretation of the word. The word hamartia refers not to a flaw in the protagonist’s personal character, but rather to an error of some kind in the protagonist’s actions or judgment. There is a subtle, but highly significant distinction here. A “tragic flaw” as we are used to thinking about it is when there is something wrong with the hero’s personal character, but a hamartia is an action or decision the protagonist makes.

Thus, while English teachers are used to teaching students that Oidipous’s “tragic flaw” in the play Oidipous Tyrannos is his hubris, this is actually a doubly wrong interpretation, because, first of all, a hamartia is not a “tragic flaw,” but rather a mistake in action or judgment. Oidipous makes several hamartiai in Oidipous Tyrannos, but his greatest is his failure to realize that Polybos and Merope are not his real parents. Again, this is an action or a decision, not a character trait.

Second of all, while Oidipous certainly displays immense pride in Oidipous Tyrannos, whether or not he actually commits any acts of hubris is debatable. His desire to avoid fulfilling the oracle’s prediction that he will murder his father and marry his mother is perfectly natural, perfectly expected, and not at all hubristic.

If any of Oidipous’s actions can truly be considered hubris, then it is not his effort to avoid fulfilling the oracle’s prediction, but rather the violent act of killing his father Laios on the road to Thebes, which I at least would consider an act of wanton and unnecessary violence that transgresses against the natural order.

ABOVE: The Murder of Laius by Oedipus, painted in 1867 by the French historical painter Joseph Blanc

Furthermore, as I noted above, not all protagonists in ancient Greek tragedies commit a hamartia. The idea that every tragedy should include a hamartia originates from Aristotle’s Poetics, in which Aristotle cites Oidipous Tyrannos and the lost tragedy Thyestes by Euripides as what he considered to be model tragedies in regards to having a hamartia. Aristotle did this, however, because he personally thought tragedies should include a hamartia, not because they always actually did.

Misconception #6: The tragedy of Oidipous has a special resonance because all men have a secret, inner desire to murder their fathers and have sex with their mothers.

The so-called “Oedipus complex” is an idea that was originally proposed in 1899 by the Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud (lived 1856 – 1939) in his book The Interpretation of Dreams. In case you have been fortunate enough to have not been taught Freud’s ridiculous blather, according to Freud, all young male children secretly harbor jealousy and resentment towards their fathers and lust after their mothers.

This is known as the “Oedipus complex,” named after the character of Oidipous in Sophokles’s Oidipous Tyrannos. According to Freud, this complex is usually resolved by the child coming to identify himself with his father and adopting his father’s manners. Freud claimed that failing to resolve this complex in childhood could lead to all sorts of horrifying mental disorders in adulthood, such as neurosis, homosexuality, pedophilia, and masturbation. Freud writes in Chapter V of The Interpretation of Dreams:

“His [i.e. Oidipous’s] fate moves us only because it might have been our own, because the oracle laid upon us before our birth the very curse which rested upon him. It may be that we were all destined to direct our first sexual impulses toward our mothers, and our first impulses of hatred and violence toward our fathers; our dreams convince us that we were. King Oedipus, who slew his father Laius and wedded his mother Jocasta, is nothing more or less than a wish-fulfilment- the fulfilment of the wish of our childhood. But we, more fortunate than he, in so far as we have not become psychoneurotics, have since our childhood succeeded in withdrawing our sexual impulses from our mothers, and in forgetting our jealousy of our fathers. We recoil from the person for whom this primitive wish of our childhood has been fulfilled with all the force of the repression which these wishes have undergone in our minds since childhood. As the poet brings the guilt of Oedipus to light by his investigation, he forces us to become aware of our own inner selves, in which the same impulses are still extant, even though they are suppressed.”

This whole notion has absolutely no scientific evidence to support it and Freud basically just made it up. Freud lived back in the early days of psychology, before Ivan Pavlov and before Karl Popper when basically all you needed to say to call something “psychology” was essentially, “You know what, I have no evidence to support this, but it sounds about right to me.”

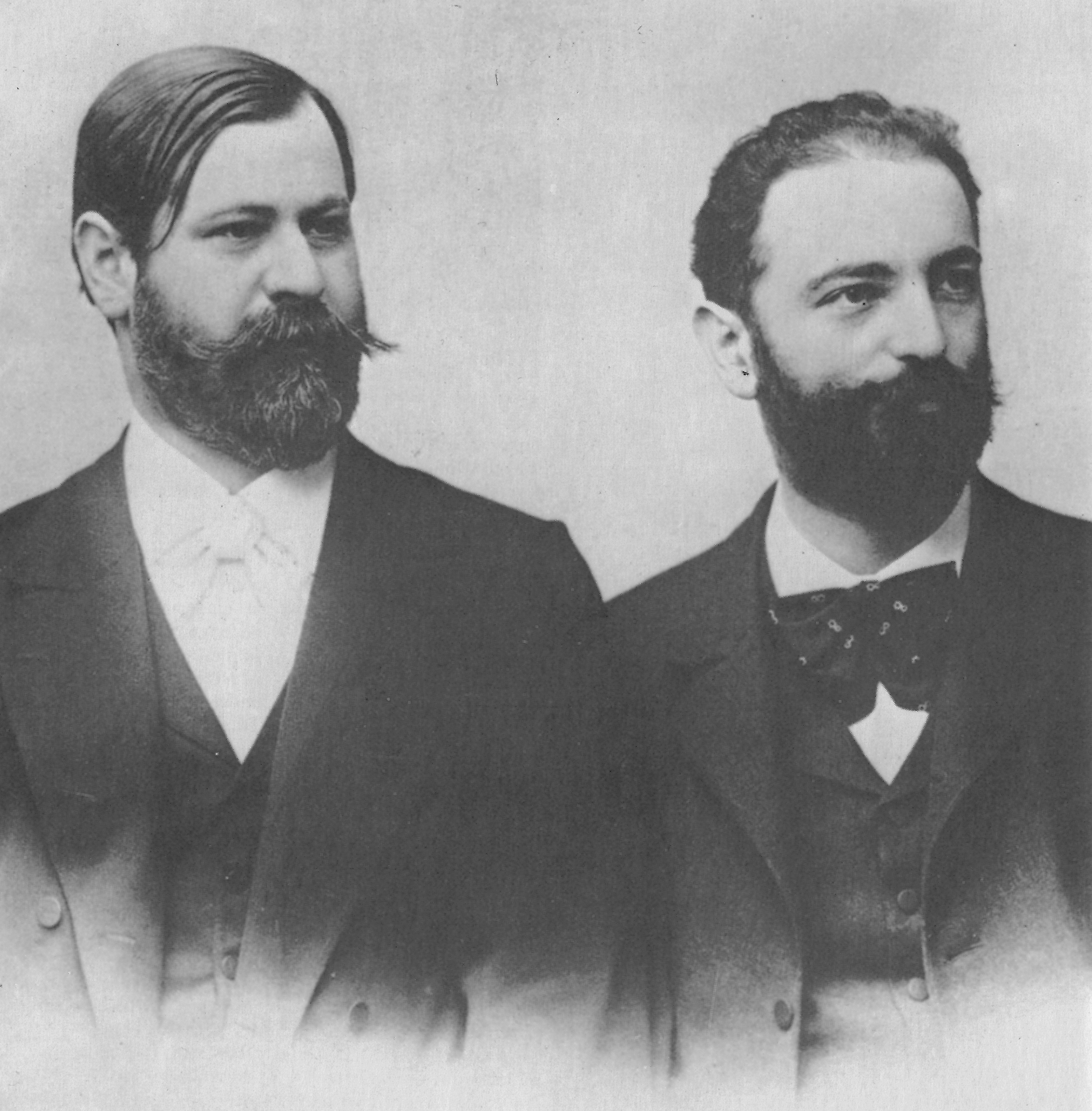

Just to give you an impression of how wildly unscientific psychology was during Freud’s time, one of Freud’s closest friends and colleagues was the German otorhinolaryngologist Wilhelm Fleiss (lived 1858 – 1928), who honestly and sincerely believed that the nose was actually the location of the mind, not the brain. Fleiss was a certifiable nutcase, but his ideas were highly influential on Freud. Freud took from Fleiss, for instance, the idea of “innate bisexuality” and even called Fleiss “the Kepler of biology.”

ABOVE: Photograph of Sigmund Freud with his friend Wilhelm Fleiss, who believed that the nose was most important organ in the body for understanding thought

The field of psychology has obviously come a long way since Freud’s time and Freud’s notion of the “Oedipus complex” was long ago discarded, but, for some reason, Freudian psychoanalysis is still popular among literary critics, even though it is complete nonsense. It also remains popular among members of the general public.

In any case, even if the Oedipus complex was a real thing, there is absolutely nothing in the text of Sophokles’s tragedy Oidipous Tyrannos that even remotely seems to imply Oidipous has a subconscious desire to murder his father and marry his mother. On the contrary, in the play, Oidipous does everything he can to avoid murdering his father and marrying his mother. He desperately doesn’t want to do it.

The only reason why Oidipous does end up murdering his father and marrying his mother is because he makes a hamartia (i.e. a mistake in action); he wrongly assumes that his parents are the king and queen of Corinth and fails to consider the possibility that his parents might be someone else, like, say, the king and queen of Thebes. The tragedy is not about Oidipous trying to resist a subconscious desire and failing; it is about Oidipous making a huge mistake and reaping the consequences of that mistake.

Furthermore, at the end of the play, when Oidipous finally discovers that he has indeed murdered his father and married his mother, he is so disgusted and distraught at his own actions that he gouges out both his eyes. Does that sound like something that someone who secretly wanted to do what he did all along would do?

The story of Oidipous is not relatable because all men secretly desire to murder their fathers and have sex with their mothers, but rather because Oidipous goes on a mission to find out the truth and discovers something truly horrifying about himself that he never knew. Even though his case is far more extreme than anything most of us have ever done, we still can relate because we have all found out things about ourselves at various points in our lives that we do not like.

ABOVE: Photograph of the Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud taken in around 1921. Freud was a certifiable crank with all kinds of nutty ideas.

Misconception #7: In Sophokles’s Oidipous Tyrannos, Oidipous is a helpless victim of fate ordained by the gods to murder his father and marry his mother.

Most English students who read Oidipous Tyrannos in high school English class are taught that the play is fundamentally about fatalism; essentially, they are taught that Oidipous is a helpless victim of fate and that he simply could not have avoided his fate because the gods had ordained it.

This is not a correct or useful interpretation of the play either. Everything that Oidipous does in the play, he does of his own free will; he just does not always realize what he is doing. Do you know how we know? Because he outright says so. Towards the end of the play, Oidipous declares, as translated by Albert S. Cook:

“It was Apollo, my friends, Apollo,

who fulfilled my evil, these my evil

sufferings. But the murderous hand that

struck me was no one’s but my own,

wretch that I am!”

The oracle’s prediction that he will murder his father and marry his mother is nothing more than an accurate prediction of future events. The oracle does not in any way “force” Oidipous to fulfill the prophecy. As the scholar E. R. Dodds explains in an excellent article titled “On Misunderstanding the ‘Oedipus Rex,'” the ancient Greeks believed simultaneously that people make their own choices, but also that the prophecies of oracles are always correct. They saw no contradiction between these two ideas.

In other words, the oracle accurately foretells what Oidipous will do simply because oracles always accurately foretell the future, not because the oracle’s warning “forced” Oidipous to do anything. Dodds also notes that it is precisely the way Oidipous’s own actions lead to his downfall that make his story so compelling and, if we reduce him to a mere puppet of fate, then we lose something important in the story.

Conclusion

Here is a summary of the main points I have explained in this article:

- Ancient Greek tragedy is not defined as a genre by the protagonist dying or suffering a downfall at the end, but rather by the fact that the plays are centered around important figures, such as gods, heroes, kings, and mythological figures and are always set in the distant, mythological past or in a distant, foreign land.

- Ancient Greek comedy changed significantly over the course of its history and can actually be divided into three phases: Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, and New Comedy.

- Hubris is not “excessive pride,” but rather extreme and unwarranted insolence, aggression, or violence characteristic of an act that violates or implies intention to violate the natural order of the cosmos as ordained by Zeus and the other gods.

- A hamartia is not a “tragic flaw,” but rather an error in action or judgement.

- The so-called “Oedipus complex” is pure pseudoscience; the story of Oidipous is relatable not because every man secretly desires to murder his father and have sex with his mother, but rather because Oidipous goes on a mission to discover the truth and uncovers something very disturbing about himself in the process, something we all can relate to more-or-less.

- In Oidipous Tyrannos, Oidipous is not a helpless “victim of fate” ordained by the gods to do what he does; he does it all of his own volition, but in ignorance of what he is really doing, and the oracle merely accurately predicts it in advance.