Everyone thinks they know history, but there are a lot of facts about history, specifically about the chronology of events, that may surprise you: from events that people think should have happened in different time periods that actually happened around the same time to events that people think happened in the same time period that really happened hundreds, if not thousands, of years apart. Here are just a few particularly mind-bending examples that will change how you think of history:

#1. The founding of the University of Oxford predates the Aztec Empire by centuries.

The University of Oxford was founded in the late eleventh century AD and there is definite historical record that classes were already being taught there in around the year 1096. The university grew considerably after King Henry II of England banned English students from studying at the University of Paris in 1167 and it soon gained a reputation as the most prestigious center of higher education in England.

By sharp contrast, the Mexica (the people who made up the ruling nation of the Aztec Empire) first arrived in central Mexico in the mid-1200s, at a time when the University of Oxford was already thriving. They founded their capital city of Tenochtitlan on the site of present-day Mexico City in around 1325 and they crowned their first tlatoani (“ruler”) Acamapichtli in around 1375. Their empire did not become dominant in the region until the 1400s.

That means that a university renowned today as one of the greatest in the world and a center of forward thought and intellectual progress is actually centuries older than an empire that is best known to most westerners today for the large number of human beings they sacrificed.

ABOVE: Illustration from the Aztex Codex Mendoza, dating to between 1529 and 1553, depicting a human sacrifice

#2. The height of the witchcraft hysteria in western Europe happened during the height of the so-called “scientific revolution.”

Today, most people wrongly believe that the witch trials happened during the Middle Ages (c. 476 – c. 1453 AD). This idea could not be any further from the truth. In ironic reality, any accusation of witchcraft during the Middle Ages was far more likely to result in the person making the accusation being punished or executed than the person being accused.

Throughout almost the entirety of the Middle Ages, the official position of the Catholic Church was that witches did not exist and that belief in witchcraft was an ignorant pagan superstition. Consequently, anyone who believed in witchcraft was deemed guilty of heresy and was liable to be punished as such if the person persisted in this view after being warned to abandon it. A person who openly claimed to be a practitioner of magic could be tried for heresy.

It was not until the late 1300s that belief in witchcraft even became accepted as potentially orthodox and it was not until the early 1500s that it became considered mainstream. The witchcraft hysteria actually reached its peak in the late 1500s and early 1600s and continued until the end of the seventeenth century. Do you know what also happened during that time period? The Northern Renaissance and the so-called “scientific revolution.” William Harvey, William Shakespeare, Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, Galileo Galilei, René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, John Locke, Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, Isaac Newton, and Montesquieu all lived during the height of the witch trials.

To us looking back on it, it seems baffling that the same era that produced so many original thinkers and the birth of modern science was also an era when thousands of people were being tried and executed for witchcraft. To reconcile this, people naturally assume that witch-trials must have instead belonged to an earlier era, one which is already notorious for its alleged barbarism: the so-called “Dark Ages.”

For more misconceptions about the witch trials, here is a link to a much more extensive article I wrote on the subject back in October 2018.

ABOVE: Nineteenth-century woodcut depicting a witch burning

#3. Cleopatra actually lived closer to the present day than to the time of the pyramid-builders.

In popular culture, events from ancient history tend to get lumped together. This is mainly because, unfortunately, most people know very little about ancient history. Many people imagine “ancient Egypt” as having a history something similar to the span of modern United States history: just a few hundred years or so. Others imagine something closer to the span of English history: maybe 1,500 years or so. In reality, the history of ancient Egypt was incredibly longer and more complex than most people realize. Ancient Egyptian civilization emerged in the late fourth and early third millennia BC and changed drastically over the course of its roughly 4,500-year history.

The earliest Egyptian pyramid with smooth sides is the Bent Pyramid at Dahshur, which was built during the reign of Pharaoh Sneferu, who ruled c. 2613 – c. 2589 BC. The Great Pyramid at Giza was built during the reign of the Pharaoh Khufu, who ruled c. 2589 – c. 2566 BC. By contrast, Cleopatra was born in early 69 BC and died on either August 10 or August 12, 30 BC at the age of thirty-nine. That means that Cleopatra lived closer to the twenty-first century than to the time of the pyramid-builders by hundreds of years.

Just consider this: the complex world in which Cleopatra lived in the first century BC—where different civilizations were in close contact with each other, Egypt was thoroughly permeated by Greek culture, and the Roman Empire was growing ominously in the west—would have been equally (if not even more) foreign to the pyramid-builders of the twenty-sixth century BC as our world in the twenty-first century AD would be to her. Yet, for some reason, most people just lump everything that happened over the course of ancient Egyptian history together into one box and call it “ancient Egypt.”

ABOVE: Contemporary realistic portrait head of Kleopatra VII Philopator of Egypt (i.e. “Cleopatra”) from the Altes Museum in Berlin Germany

#4. There were still at least a few woolly mammoths alive on earth at the time when the Pyramids of Giza were being built.

Woolly mammoths went regionally extinct in most areas between 14,000 and 10,000 years ago, but small, isolated populations survived until much later. The last known population of living woolly mammoths on the Eurasian mainland was in the Kyttyk Peninsula of Siberia. This population died off around 9,650 years ago.

A small population of woolly mammoths survived on St. Paul Island off the coast of Alaska until around 3600 BC, just a few hundred years before the invention of the earliest form of cuneiform writing by the Sumerians in Mesopotamia in around 3200 BC. The very last woolly mammoths survived on Wrangel Island off the coast of Siberia until between roughly 2000 and 1700 BC—between roughly 4,000 and 3,700 years ago.

As I mentioned above, the Great Pyramid of Giza was constructed sometime between roughly c. 2589 and c. 2566 BC during the reign of the pharaoh Khufu. The Pyramid of Khafre was constructed sometime roughly between c. 2558 and c. 2532 BC. The Pyramid of Menkaure was constructed sometime roughly between c. 2532 and c. 2510 BC. That means that all three of the major pyramids of Giza predate the last of the woolly mammoths. This should give you an impression of both just how old the pyramids are and how recently woolly mammoths really went extinct.

ABOVE: Model of a woolly mammoth from the Royal BC Museum in Britain. The last woolly mammoths died out after the pyramids were built.

#5. The first color photograph that could permanently retain its coloration was taken during the first year of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency.

The first color photographs were taken in the early 1800s. These early color photographs relied on purely chemical processes and the colors on these quickly faded and vanished within a few days. The first color photograph that could permanently retain its coloration was taken in 1861, the same year Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as president of the United States, by the English photographer Thomas Sutton (lived 1819 – 1875) under the direction of the renowned Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell (lived 1831 – 1879) using the method Maxwell had first proposed in a paper he had published in 1855.

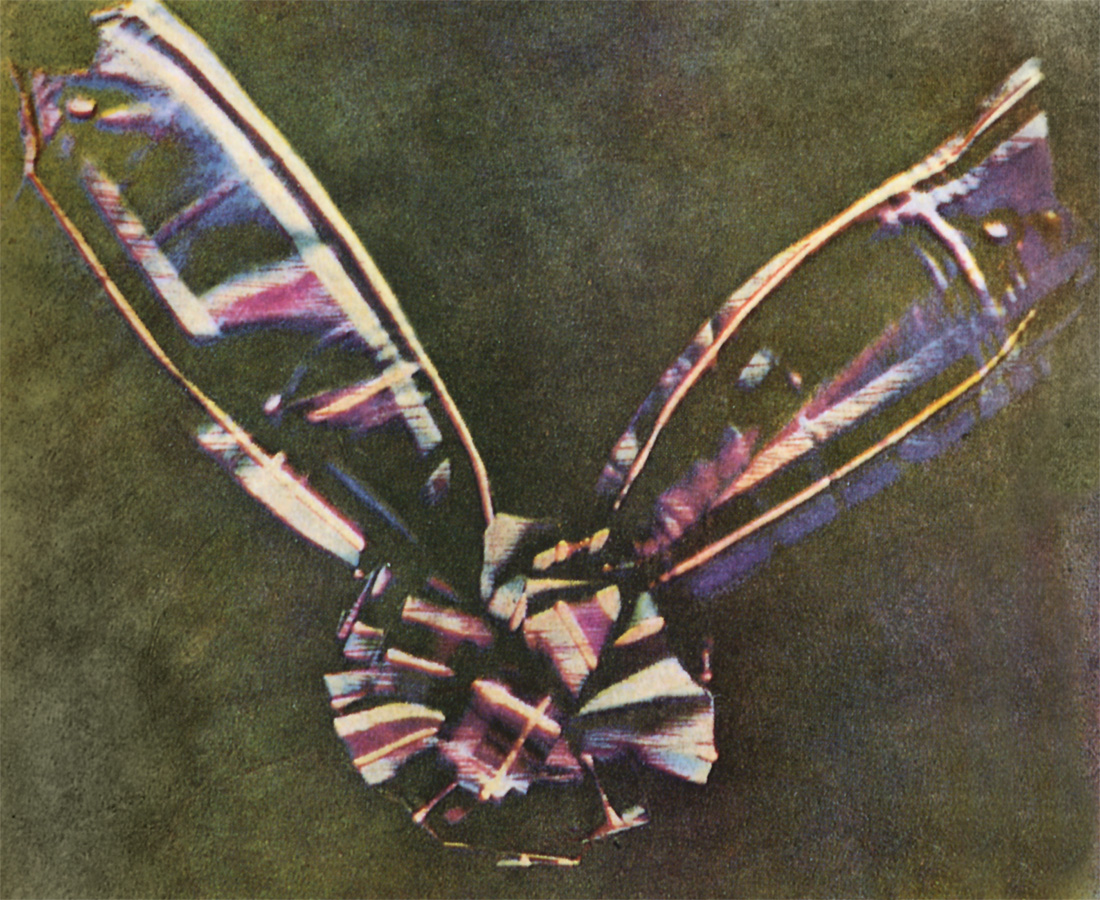

The photograph was of a tartan ribbon. Under Maxwell’s guidance, Sutton produced this photograph by taking three black-and-white photographs of the ribbon through a green filter, a blue filter, and a red filter. He then projected all three images superimposed onto a screen, thus producing a color image. Here it is, the very first permanent color photograph:

Color photography grew more sophisticated over the years and, by the beginning of the twentieth century, people were taking remarkably high quality color photographs. Between 1905 and 1915, the Russian photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky (lived 1863 – 1944) travelled throughout the Russian Empire taking color photographs that look almost downright modern.

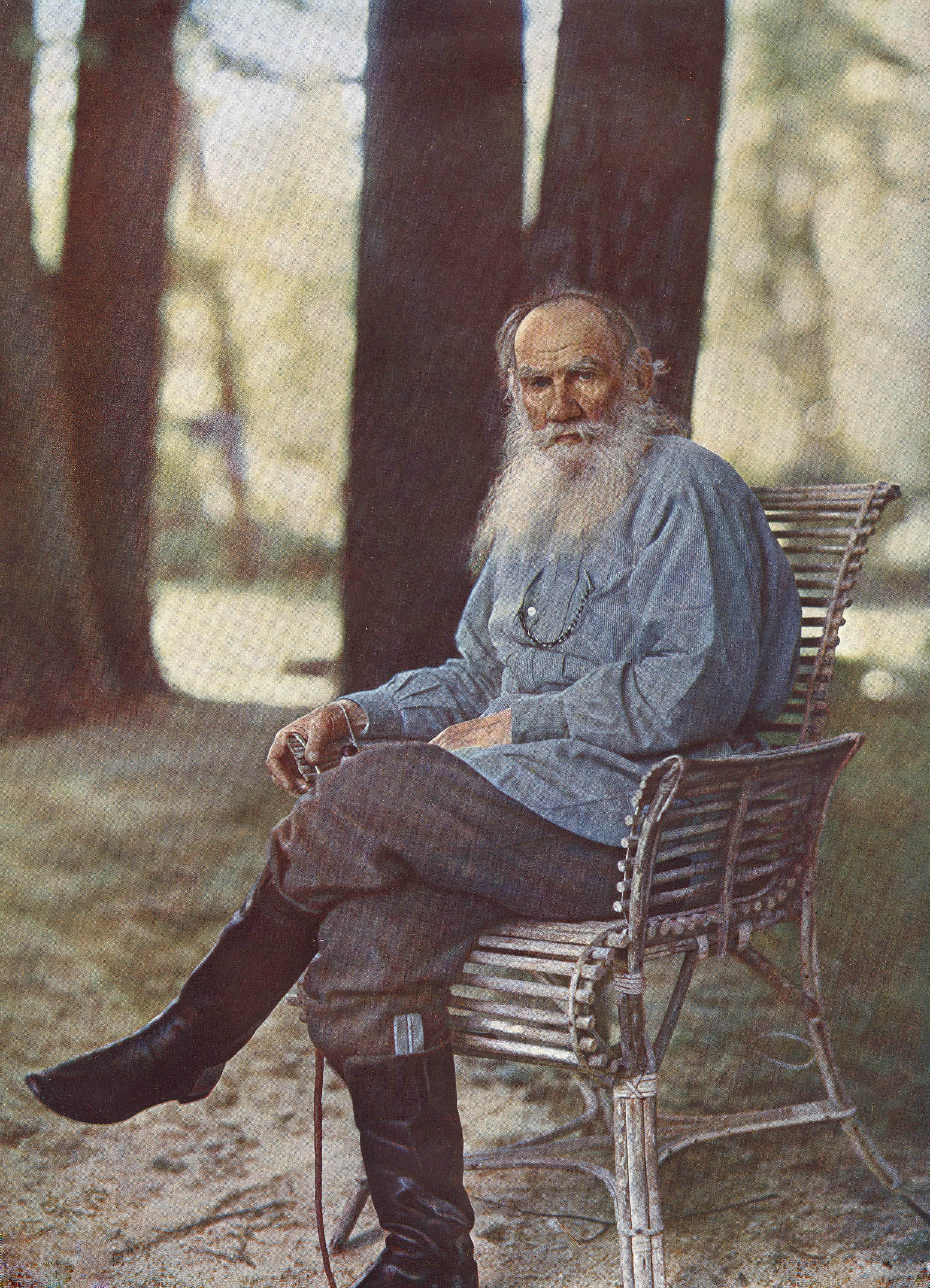

Here is a color portrait of the famous Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy (lived 1828 – 1910), author of the novel War and Peace, taken by Prokudin-Gorsky on May 23, 1908:

Here is a photograph of Alim Khan, the emir of Bukhara, taken by Prokudin-Gorsky in 1911:

Here is a photograph taken by Prokudin-Gorsky of Jewish children with their rabbi in Samarkand:

Here is a photograph by Prokudin-Gorsky of an Italian woman dressed in formal attire:

#6. If you were born before 2007, slavery was legal in at least one country within your lifetime.

While many people wrongly believe that slavery ended in the 1800s, slavery actually still exists today in various forms. In fact, until just twelve years ago, slavery was actually legal in some parts of the world. The last country to formally abolish slavery was Mauritania, which did so in 2007. Take a moment to process that fact. This means that, within the lifetime of almost everyone reading this, slavery was actually still officially legal in a country which, at that time, is estimated to have had a population of roughly 3.313 million people.

Now slavery is officially illegal in every country on earth. Unfortunately, that does not mean that slavery is gone. Even today in the twenty-first century, there is still an estimated roughly 40.3 million people who are currently being illegally held in various forms of slavery worldwide. Slavery is still a major, current problem; nowadays, though, most people use the more euphemistic-sounding name “human trafficking” to refer to what is essentially still slavery.

ABOVE: Illustration from c. 1866 showing Arab slave traders in Mozambique leading their captives along the Ruvuma River

Scientifically speaking, there is no such thing as a “white race.” Some people may have paler or darker skin than others, but the color of a person’s skin is just one very superficial trait. In the 1970s, the American geneticist R. C. Lewontin found that there is actually greater genetic diversity within so-called “racial groups” than there is between them. It is possible for a “black” man to have more genetically and physically in common with a “white” man from Europe than another “black” man. Since then, other geneticists have confirmed his findings. The problem is that racialists latch onto a tiny handful of obvious physical features and ignore all the other traits.

The notion of a “white race” is a cultural concept that was invented in the Early Modern Period to justify the enslavement and mistreatment of people of African descent. No one prior to the Early Modern Period ever identified as “white” in a racial sense. Furthermore, the definition of who counts as “white” has shifted greatly over the course of history. For instance, in the nineteenth century, there were many people who did not consider the Irish “white.”

For instance, in 1899, the English racist H. Strickland Constable published a book titled Ireland from One or Two Neglected Points of View in which he explicitly argued that the inhabitants of Ireland were Africans and that they were therefore racially inferior creatures deserving of subjugation. This idea is expressed implicitly in many other sources from the time period. Today, though, virtually everyone regards the notion of the Irish not being “white” as ridiculous.

We should entirely dispose of the ridiculous notion that there is a “white race”; it is a totally arbitrary classification based on incredibly superficial physical features. All human beings belong to the same race and all human beings have inherent value.

I think this exchange demonstrates the extent to which you have drunk the alt-right Cool Aid; when I say that “race” is a social construct and that all human beings have inherent value—both of which are views that have been widely accepted among liberals and progressives in this country for over half a century—you can find no other response but to accuse me of trolling, because these ideas are apparently so alien to you that you cannot imagine someone like me would seriously argue for them. I assure you, though, that I am not trolling.

E. Harding is a terrible human being Spencer.

You’d be within rights to delete him and his racialist twaddle.

You might want to review some of the other science out there – the first migrants, 10000 years ago to the British Isles had dark skin and possibly blue eyes. However they are directly genetically linked to people in area where those early remains were found – Cheddar in Somerset. There’s a strong case for traits such as fair skin being acquired as a response to the environment. In extreme latitudes the lack of sunlight means that melanin is disadvantageous, so levels in the skin fall over the generations. And as Spencer says the whole notion of race is illusory – and he’s absolutely right that there is more genetic diversity in Africa than the rest of the world so indeed a Western European and a Han Chinese person might share more genes in common than two people from different parts of Africa. As for the Celts being ‘related’ to eastern Europeans explaining ‘a ton’ what exactly are you implying?

This whole line of argument is, in any case, a complete cul de sac. Scientific racism was a neat 19th century ruse to justify colonialism. There are no hard genetic boundaries between one group of humans and another. We all blend in. Pfft.

Slavery was legal in at least one country that had a registered Internet TLD (Top Level Domain).

Dear Mr. McDaniel,

Speaking of the sources and references you use:

(1) Do you use various fact-based sources like Britannica and/or World Book Encyclopedia (i.e. physical print or online) in your research process?

(2) I learned in my American history class during high school (circa 1995-1997), that we had black-and- white photography during the 1860’s. But, I honestly had no idea that color photography was being used as early as the 1900’s.

Thanks again for another great article.

Fin.