Hardly anyone nowadays believes the earth is flat. Many people, however, wrongly believe that people during the Middle Ages thought the world was flat. In reality, however, the sphericity of the earth was common knowledge throughout the entire Middle Ages. The idea that people in the Middle Ages thought the earth was flat is a canard invented in the Early Modern Period by authors who wanted to portray the Middle Ages as a time of backwardness and superstitious regression.

Origins of the model of the spherical earth

There really was a time when people did believe that the earth was flat, but it was long, long before the Middle Ages. Prior to around 500 BC or thereabouts, it seems most people believed that the earth was flat like a table and that the sky was a dome covering it. This, for instance, seems to have been the worldview of the ancient Sumerians and other early Mesopotamians, the pharaonic Egyptians, and the authors of the Hebrew Bible.

Interestingly, although the authors of the Hebrew Bible seem to agree that the earth is flat, they don’t seem to have had a clear impression of what shape it is. You can find contradictions about the shape of the earth even within the same book. For instance, the Book of Isaiah 11:12 mentions there being “four corners of the earth,” which makes it sound as though the earth is flat and shaped like a square. The Book of Isaiah 40:22, however, describes the earth as a “circle”:

“It is he who sits above the circle of the earth,

and its inhabitants are like grasshoppers;

who stretches out the heavens like a curtain,

and spreads them like a tent to live in;”

The early Greeks believed that the earth was flat too. The prevailing view among the early Greeks seems to have been that the earth was disc-shaped:

- The Iliad and the Odyssey describe the world as flat, with the Underworld lying beneath the ground and Tartaros lying beneath the Underworld.

- The philosopher Anaximenes of Miletos (lived c. 586 – c. 526 BC) describes the earth in fragment 13.A.6 as “πλατεῖαν μάλα,” which means “very flat.”

- The philosopher Anaxagoras of Klazomenai (lived c. 510 – c. 428 BC) repeatedly describes the earth in his surviving fragments as “πλατείας,” meaning “flat.”

- The poet Empedokles of Akragas (lived c. 494 – c. 434 BC) describes the earth in fragment 31.A.56 as “κυκλοτερής,” which means “circular” or “disc-shaped.”

We do not know who the first person to propose the notion of the sphericity of the earth was. The Greek biographer Diogenes Laërtios, who lived in around the third century AD, cites conflicting reports in his book The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers claiming that the sphericity of the earth was discovered by the poet Hesiodos of Askre (lived c. eighth century BC), by the philosopher Pythagoras of Samos (lived c. 570 – c. 495 BC), or by the philosopher Parmenides of Elea (lived c. 515 – late fifth century BC). Here is the passage in question, as translated by R.D. Hicks:

“Favorinus says that our philosopher [i.e. Pythagoras] used definitions throughout the subject matter of mathematics ; their use was extended by Socrates and his disciples, and afterwards by Aristotle and the Stoics. Further, we are told that he was the first to call the heaven the universe and the earth spherical, though Theophrastus says it was Parmenides, and Zeno that it was Hesiod.”

All three of these reports are most likely spurious. Hesiodos’s poems have survived and they strongly indicate that he believed the earth was flat. The claim that Pythagoras discovered the sphericity of the earth seems to be based solely on a pseudepigraphical poem written long after the historical Pythagoras’s death. Finally, we know about Parmenides’s cosmology from surviving fragments of his work and from his appearance in Plato’s dialogue Parmenides and he doesn’t seem to have been a round-earther.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of a Roman marble bust of the Greek philosopher Pythagoras on display in the Capitoline Museum. The representation here is fictional; no one knows what Pythagoras really looked like.

We do know, however, that, by around the end of the fifth century BC or thereabouts, the sphericity of the earth was common knowledge among educated people in the Greek world. The Athenian philosopher Plato (lived c. 428 – c. 347 BC) explicitly describes the earth as spherical in his Phaidon 108d-109a, in which one of his speakers says this, as translated by Harold North Fowler:

“…the earth is round and in the middle of the heavens, it needs neither the air nor any other similar force to keep it from falling, but its own equipoise and the homogeneous nature of the heavens on all sides suffice to hold it in place; for a body which is in equipoise and is placed in the center of something which is homogeneous cannot change its inclination in any direction, but will remain always in the same position. This, then, is the first thing of which I am convinced.”

Plato’s student Aristotle of Stageira (lived 384 – 322 BC), whose writings were widely studied during the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance, presents several cogent arguments for the sphericity of the earth in Book Two of his treatise On the Heavens, based on empirical evidence:

- Gravity pulls all matter towards the center of the earth, which inevitably results in a planet that is roughly spherical.

- The earth always casts a circular shadow on the moon during a lunar eclipse. A sphere is the only shape that always casts a circular shadow no matter what direction the light is hitting it from.

- When a person travels north or south, the stars that are visible change, meaning the surface of the earth must be curved.

Aristotle’s evidence for the sphericity of the earth was so compelling that basically every educated person writing after him accepted the earth as spherical.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of a Roman marble bust of Aristotle. The oldest surviving argument for the sphericity of the Earth based on empirical evidence comes from Aristotle.

Perhaps the only Greek flat-earther after Aristotle who is worth mentioning is the philosopher Epikouros of Samos (lived 341 – 270 BC), a younger contemporary of Aristotle who founded his entire philosophy on the rejection of Plato and made a point to disagree with Plato on just about everything he possibly could.

Epikouros probably only embraced flat-earthism because he didn’t have access to a copy of Aristotle’s On the Heavens and he wasn’t aware of the empirical evidence for the sphericity of the earth. If he had had access to a copy of the book, I suspect he probably would have accepted that the earth is a sphere, since he firmly believed in empiricism.

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of a Roman marble bust of the ancient Greek philosopher Epikouros of Samos, who was a flat-earther

Evidence for belief in a spherical earth during the Middle Ages

Knowledge of the sphericity of the earth did not disappear with the end of classical antiquity in the fifth century AD; on the contrary, sphericity remained well-known among scholars. The Northumbrian monk Bede the Venerable (lived c. 672 – 735 AD) clearly outlines the mainstream position of medieval scholars in his treatise On the Reckoning of Time, which is that the earth is roughly a sphere. Bede writes in chapter 46, as translated by William D. McCready:

“We refer to the sphere of the earth, not that it is perfectly spherical in shape, given the great difference of mountains and plains, but that it would constitute a perfectly formed sphere if all of the lines were enclosed in the circumference of its circuit. Hence it is that the stars of the northern region are always visible to us, while southern ones never are. Conversely, these northern stars are never seen in southern regions, owing to the obstruction of the globe of the earth. The country of the Troglodytes, and Egypt, which is adjacent to it, do not see the Great and Little Bear, and Italy does not see Canopus.”

Around five hundred years after Bede, a scholar named Johannes de Sacrobosco (lived c. 1195 – c. 1256 AD) wrote an introductory astronomy textbook titled Tractatus de Sphaera, which was used for centuries after his death and has survived to the present day. In the very first chapter, Johannes states that the earth is a sphere and explains how astronomers know this. Here is his explanation, as translated by Lynn Thorndike:

“That the earth, too, is round is shown thus. The signs and stars do not rise and set the same for all men everywhere but rise and set sooner for those in the east than for those in the west; and of this there is no other cause than the bulge of the earth. Moreover, celestial phenomena evidence that they rise sooner for Orientals than for westerners. For one and the same eclipse of the moon which appears to us in the first hour of the night appears to Orientals about the third hour of the night, which proves that they had night and sunset before we did, of which setting the bulge of the earth is the cause.”

“That the earth also has a bulge from north to south and vice versa is shown thus: To those living toward the north, certain stars are always visible, namely, those near the North Pole, while others which are near the South Pole are always concealed from them. If, then, anyone should proceed from the north southward, he might go so far that the stars which formerly were always visible to him now would tend toward their setting. And the farther south he went, the more they would be moved toward their setting.”

“Again, that same man now could see stars which formerly had always been hidden from him. And the reverse would happen to anyone going from the south northward. The cause of this is simply the bulge of the earth. Again, if the earth were flat from east to west, the stars would rise as soon for westerners as for Orientals. which is false. Also, if the earth were flat from north to south and vice versa, the stars which were always visible to anyone would continue to be so wherever he went, which is false. But it seems flat to human sight because it is so extensive.”

Medieval depictions of the earth consistently show it as a sphere. For instance, below is a twelfth-century manuscript illustration from the Liber Divinorum Operum by Hildegard of Bingen, showing the earth as a sphere. Notice that the people and trees are correctly shown extending from the earth radially:

Here is a fourteenth-century illustration from a manuscript copy of L’Image du Monde, originally written by the French priest and poet Gautier de Metz in around 1246:

Another piece of evidence in support of the fact that it was commonly known that the earth is spherical during the Middle Ages is the fact that one of the primary symbols of kingship during the Middle Ages was the globus cruciger, a sphere with a cross on top of it. The sphere was supposed to represent the earth and the cross was supposed to represent Christ’s dominion over it. Clearly it must have been common knowledge that the earth was spherical, or else the globus cruciger would not have been a meaningful symbol.

As popular science historian Stephen Jay Gould summarizes in his book Dinosaur in a Haystack: Reflections on Natural History, “there never was a period of ‘flat Earth darkness’ among scholars (regardless of how the public at large may have conceptualized our planet both then and now). Greek knowledge of sphericity never faded, and all major medieval scholars accepted the Earth’s roundness as an established fact of cosmology.”

ABOVE: Photograph from Wikimedia Commons of a globus cruciger

Genuine medieval flat-earthers

There were a few people during the Middle Ages who did believe that the earth was flat. Notably, the Christian apologist Lactantius (lived c. 250 – c. 325 AD), who came from what is now Tunisia, mocked the idea of a spherical earth. He is the only writer of his era known to have done this, however.

A few centuries later, an extreme Bible literalist named Kosmas Indikopleustes (lived c. 500 – after c. 550 AD) wrote a book titled Christian Topography in which he advanced the bizarre thesis that the earth is actually shaped like the Ark of the Covenant, with a flat bottom, walls, and a lid on top. No one took his ideas seriously, though, and he was universally regarded as an eccentric crank.

It’s worth pointing out that people like Kosmas Indikopleustes still exist. Today, there are multiple organizations devoted to promoting the claim that the earth is flat, the most famous of which is the Flat Earth Society. The wiki on their official website declares:

“This website is dedicated to unravelling the true mysteries of the universe and demonstrating that the earth is flat and that Round Earth doctrine is little more than an elaborate hoax.”

“The Flat Earth Society holds that there is a difference between believing and knowing. If you don’t know something, and cannot understand it by first principles, then you shouldn’t believe it. We must, at the very least, know exactly how conclusions were made about the world, and the strengths and weaknesses behind those deductions. Our society emphasizes the demonstration and explanation of knowledge.”

Of course, all flat-earthers really need to do to find out how we know the earth is a sphere is read Aristotle’s On the Heavens, in which he explains how you can tell the earth is a sphere on your own without even looking at modern photographs taken from space.

ABOVE: Logo of the modern-day “Flat Earth Society.” Believe it or not, these clowns still exist today in the twenty-first century.

Origins of the myth of the flat earth

It is not entirely clear where the idea that people in the Middle Ages thought the earth was flat originates from, but there are scattered references to it in a few books published in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. These references primarily come from works written by authors who were vocal critics of the Roman Catholic Church and organized religion in general.

The American Founding Father Thomas Jefferson (lived 1743 – 1826), for instance, mentions the alleged medieval belief in a flat earth in a chapter of his Notes on the State of Virginia written in 1784, incorrectly stating that the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei (lived 1564 – 1642) was prosecuted by the Inquisition for saying that the earth was a sphere. Jefferson writes:

“Government is just as infallible too when it fixes systems in physics. Galileo was sent to the inquisition for affirming that the Earth was a sphere: the government had declared it to be as flat as a trencher, and Galileo was obliged to abjure his error. This error however at length prevailed, the Earth became a globe, and Descartes declared it was whirled round its axis by a vortex.”

In reality, the Catholic Church has always accepted that the earth is spherical; officially speaking, Galileo was prosecuted for claiming that the earth orbits around the sun, since the official position of the church at the time was that the sun orbits around the earth. The prosecution of Galileo, however, had a lot more to do with the fact that he had personally insulted the Pope and other prominent church authorities than it had to with actual astronomy.

In any case, the misconception that medieval people thought the earth was flat was greatly popularized by the American writer Washington Irving (lived 1783 – 1859) in his book A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, which was first published in January 1828. Irving sought to portray Columbus as a romantic hero in line with the conventional notions of heroism at the time. To show how brilliant Columbus was, Irving made up a tall tale about how people laughed at him for believing the world was spherical.

ABOVE: Daguerreotype photograph of the American writer Washington Irving, the man most directly responsible for the promotion of the misconception that people in the Middle Ages believed the world was flat, from between 1855 and 1860

As I discuss in this article I published in October 2018, the real reason why people made fun of Columbus was because his plan really shouldn’t have worked. You see, at the time, scholars actually had a very accurate idea of how large the earth was, thanks to the calculations of the Greek geographer Eratosthenes of Kyrene (c. 276 – c. 195 BC). Columbus, however, incorrectly believed that the earth was much smaller than Eratosthenes had calculated.

The scholars believed that the distance from Spain to Asia was probably about 15,000 miles. Columbus, however, believed that it was probably only around 3,000 miles. As it turns out, the scholars were right and Columbus was wrong. Fortunately, for Columbus, there turned out to be a whole continent in the Atlantic that Europeans hadn’t known existed. If the Americas hadn’t been there, he and his crew would have run out of food and supplies and would have starved to death months before they came anywhere near the coast of Asia.

Despite the fact that Irving’s book was almost completely made-up, he was already famous as an author, so it almost immediately became a bestseller. Children in grade schools across the country were routinely assigned to read it when they were learning about early European exploration of the Americas and it was widely seen as the defining book on Columbus for the rest of the nineteenth century. The book was tremendously popular in Europe as well.

By 1900, Irving’s book had sold no less than 175 print editions, including editions that were sold in both North America and Europe. Thus, Irving’s fictional story has defined how people in the United States and around the world have viewed Columbus and medieval scholars for nearly two hundred years.

In 1834, just six years after Irving’s book about Columbus was published, the claim that medieval scholars thought the world was flat saw its first appearance in a major academic publication: On the Cosmographical Ideas of the Church Fathers by the French historian Jean-Antoine Letronne, who was well-known for his strongly anti-religious views.

Letronne took a few vague and scattered references to the possibility of a flat earth from a handful of Christian writers in late antiquity and used them to argue that educated Christians throughout the Middle Ages had believed that the earth was flat. His study was deeply misrepresentative, but it proved influential nonetheless.

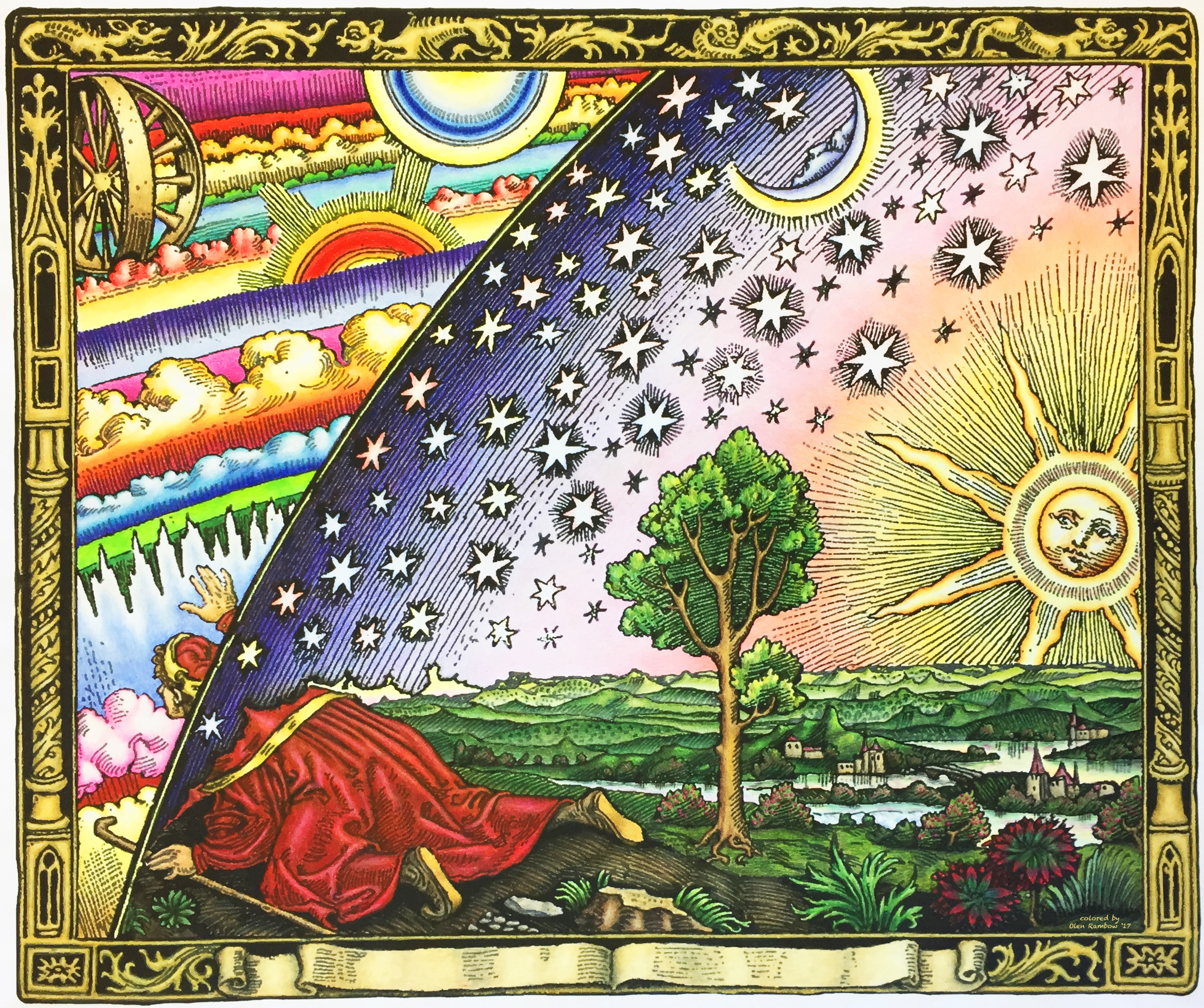

About the Flammarion Engraving

There is a certain wood engraving that has been widely shared on the internet in association with the claim that people in the Middle Ages thought the world was flat. The engraving shows a man peeking out through the dome of the sky to see the mystical workings of the universe that lie beyond. This engraving is currently the featured image for this article.

The engraving is not medieval, however; it first appeared in the book L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire (“The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology”) by Camille Flammarion in 1888. In the book, Flammarion merely describes the image as a fanciful imagining of the sky as an opaque barrier. He never claims that the image is medieval, nor does he claim that people during the Middle Ages believed that the world was flat.

Perhaps this image can teach us all a lesson: Just because something looks medieval does not mean it really is.

ABOVE: Modern colorized version of the Flammarion Engraving

People sometimes look at the round but flat medieval depictions of the world, eg the Mappa Mundi in Hereford cathedral, and a) assume that it’s meant to be a map in the modern sense of the word rather than a symbolic representation, and b) assume that it proves that medieval people thought the world was round but flat. If b) were true, modern maps of the world would be evidence that modern people believe the world to be rectangular and flat!

Many thanks from a fan of the Middle Ages! I spend a lot of time arguing that medievals were not, as a group, stupider than moderns, even if they had less factual knowledge.

That is absolutely correct. People in ancient and medieval times were every bit as intelligent as us; they merely lacked our technology and scientific knowledge. They, of course, could not have had the technology and knowledge we have today because such things are accumulative; they build over time and each new discovery must be built upon the ones that were made before it. You cannot invent the laptop computer until you have already invented all the necessary components of it. All of our knowledge today is dependent on discoveries made by our distant ancestors, including the people who lived in antiquity and the medieval period.

Biblical literatists and koran literalitists seem to have believed (believe?) the Earth was flat because the holy book said so. Paul Kruger, President of the Transvaal in the late nineteenth century, was a literalist believer in a flat Earth.

I suggest a reading of the book “Columbus The Untold Story” by Manuel Rosa (Outwater Media Group, Garfield, New Jersey, 2016). The story presented there may be twisted but it is probable – in fact more probable than accepted belief that Columbus was not aware of the size of the Earth…

I have read some of the speculation out there claiming that Christopher Columbus had actually somehow already heard about the existence of the New World before he set out on his first voyage and that he was intentionally looking for it and only pretending to be searching for a new route to the Indies. I have also, however, read much criticism of this notion. The evidence to support the idea that Columbus was intentionally looking for the New World is extremely weak and circumstantial and the traditional view that he was looking for a new route to the Indies far better fits the evidence that is currently available to us. For one thing, if Columbus had heard about the New World and he knew before he even set out on his first voyage that he was going to discover a new continent, then why on earth did he still insist, even when he was on his deathbed, that the land he had discovered was India? It is far more parsimonious to believe that Columbus genuinely believed that he had discovered a new route to the Indies.

An interesting addition to the thinking on this subject is that we (today) do not know how people in ancient times thought about the Earth. We have some indications in the few remaining ancient cultures, such as Australian Aborigines.

What is clear is that they do not think of the Earth as a distinct entity. The abstraction of ‘the planet’ from the landscape about them does not seem to be part of their thinking. As a consequence, they see themselves as part of the land and it as part of them. As there is no separation of human from the land, the idea of a distinct planet and the question of its shape are meaningless.

A more modern parallel might be the change in thinking about the human mind brought about by Sigmund Freud. Before Freud, it was difficult to discuss the human mind and the various drivers of human behavior outside a quasi-religious frame, but after Freud we have a framework for thinking about the mind in a way that allows us a connection to the anatomical reality of humans. We also have abstracted the mind from its previous context and can now think about it in ways we could not before. We can see hints of this in thinking about the planet in ancient history.

At the same time, of course, humans were navigating long distances working on the basis that the Earth was approximately spherical, even if they didn’t get to the point of making that notion explicit. Ancient people were just as intelligent as people today, but they had a different set of thinking tools and knowledge, and so they thought about things in different ways. This does not mean they thought about them any less deeply, merely differently.

Actually we have a pretty good impression of what people in the ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean worlds thought the world was like, even before they realized that the earth is a sphere, because we have ancient texts written by those peoples that contain plenty of references to their conceptions of the world. Before people realized the earth was spherical in around the early late sixth or early fifth century BC, most people seem to have thought of the earth as a flat, round surface with a series of solid domes above it.

These domes were supported on all side by mountains. (In Greek mythology, however, the dome of the sky, while held up by mountains in most places, is held up in the far west by the Titan Atlas.) These dome were usually conceived as being made of various kinds of stone or metals. The Homeric poems, for instance, which were originally composed in around the eighth century BC, refer to the dome of the sky as “bronze.” Often, especially in Near Eastern cultures, it was believed that the gods lived in a realm atop the highest of these domes known as the “Heaven of Heavens.”

Ancient peoples of the earliest times believed that, deep underground, in a dark cavern beneath the earth, lay the Underworld, which they thought was an actual, physical place, albeit one that was totally inaccessible to most of the living. They believed that both above the dome that covered the earth and beneath the Underworld lay the primeval waters of choas, out from which the earth had been born. It was believed that these waters surrounded everything, but were held back by the dome of the sky.

I recommend this excellent article, which talks about the conception of the universe described in the early books of the Hebrew Bible, which corresponds quite well with the general conception most people in the ancient world at the time had of the cosmos: https://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/ngier/gre13.htm

I believe that another piece of evidence for the non-flatness of the Earth that was accessible to the ancients was the fact that they could see the masts of a ship appearing over the horizon before the rest of the ship. I suppose this would have suggested at least some curvature, even if it didn’t amount to proof of a full sphere.

That one gets floated around a lot in popular culture, but it isn’t actually mentioned in the ancient sources and it’s not very realistic because human eyesight generally isn’t good enough to see the masts of ships sinking on the horizon. The ancient astronomer Klaudios Ptolemaios does, however, reference the fact that people on ships can observe mountains rising up out of the sea as they draw nearer. This one works better because mountains are much bigger than ships and it’s possible for people to actually see them clearly when they’re on the horizon.

Peter Gainsford, a classicist from Wellington, New Zealand, has written an excellent blog post in which he reviews the evidence for the sphericity of the earth found in ancient sources and specifically argues against the idea that it had anything to do with people seeing ships on the horizon.

Thanks for the reply. I didn’t realise that it wasn’t mentioned in the ancient sources, but that’s useful to know. I did wonder about the ability to see a ship’s mast at a distance, but I just assumed that ancient seafarers might have been more sensitized to such things. In any case, the example of mountains makes more sense.