It is certainly no secret that the film and television industry absolutely loves gladiators. In fact, the film Gladiator from 2000, directed by Ridley Scott and starring Russell Crow, has been widely credited with rekindling popular interest in the classical world in the twenty-first century. Unfortunately, almost everything Hollywood thinks it knows about gladiatorial combat is actually wrong.

Misconception #1: Gladiators were always forced to fight each other to the death.

It is true that gladiators fought each other in the arena for popular amusement, but it is not true that they always fought to the death. In fact, for most of Roman history, under most circumstances, it was actually illegal for a gladiator to kill his opponent and the Romans went to great lengths to prevent fatalities. We have no way of knowing exactly how many gladiators were killed in the arena, but it was probably a much lower number than many people today have been led to believe.

You see, contrary to what most people seem to believe, there were actually rules to gladiatorial combat and there were even referees to enforce those rules. For instance, gladiators were not allowed to strike their opponents when they were down and, if they did, they faced repercussions. Usually, a gladiator match ended when one of the gladiators submitted to his opponent, one of the gladiators was injured, or when they just became too tired to continue fighting and decided to call it a day.

ABOVE: Roman mosaic from the villa at Nenning, dating to the second or third century AD, showing a retiarius fighting a secutor in gladiatorial combat.

The reason for this is because gladiators were extremely expensive to buy, train, and maintain. Only the most physically fit slaves could even be considered to become gladiators and, once they were gladiators, they required regular workout routines, constant attention, training, and mentoring. They even had professional coaches known as lanista whose job was to prepare them for battle. Gladiator-owners always wanted a return on all that investment, so they expected their gladiators to survive to compete in as many fights as possible. Basically, if you were a gladiator-owner and half your gladiators were killed after their first fight, that would have been a massive loss on your investment. You really, really did not want that.

There was also the problem of demand. By the early first century AD, there was already vastly more demand for gladiator fights than there were gladiators available. As I mentioned before, slaves who were fit to become gladiators were difficult to come by and there was a limited supply. If every fight ended in a death, then the Romans would have quickly run out of gladiators. This would have been especially true in later centuries, as gladiator fights became more common and more extravagant. Thus, it only made sense for them to try to make the gladiators they did have last as long as possible.

Granted, some gladiators did die in the arena occasionally, but these deaths were nowhere near as common as popular culture usually makes them out to be. As I discuss in this article I have written, modern novels, films, television shows, and video games have a tendency to greatly exaggerate the level of violence that was common in the ancient world. The ancient world was still a pretty violent place by contemporary standards, but people generally didn’t just go around killing each other indiscriminately without reason.

Historians estimate that probably only around one tenth of gladiatorial games actually resulted in a single death. When gladiators did die in the arena, it was usually as the result of an accident or his opponent cheating and breaking the rule against killing. While emperors or certain other powerful figures could legally order gladiators to fight to the death, these orders generally seem to have been rare and they were, in most cases, widely frowned upon.

ABOVE: Some gladiators did die. The two gladiators marked with a Ø in this Roman mosaic from Terranova are both dead. The Ø may be intended to represent the Greek letter Θ, which may stand for the word θάνατος (thánatos), meaning “death” or “corpse”

It is important to emphasize, though, that, even if the gladiators did not fight to the death, fights could still be bloody. Obviously, you do not have to kill someone to make him bleed. Non-lethal injuries of all kinds were probably extremely common, certainly far more common than they are for modern sporting events. There are many surviving depictions showing defeated gladiators bleeding. Given that even the best medical treatment at the time was generally inadequate, it is likely that many gladiators probably died outside the arena of wounds they had suffered in it.

When fights to the death did occur, it was usually not an actual gladiator who died. The Romans commonly sentenced convicted criminals or prisoners of war to die in the arena for popular amusement. These were people who were going to be put to death anyways and whose lives were deemed unimportant.

The Romans had all sorts of horrifying and creative ways of putting people to death. Sometimes these untrained criminals and war prisoners would be forced to fight each other to the death. Other times they would be sentenced to fight unarmed and without armor against a fully armed, fully armored professional gladiator. Sometimes they would be burned alive. Other times they would be torn apart by lions or other wild animals.

The Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca the Younger (lived c. 4 BC – 65 AD) describes his own disgust at the sight of such an execution in his Moral Letter to Lucilius 7. Here is what Seneca says, as translated by Richard Mott Gummere:

“By chance I attended a mid-day exhibition, expecting some fun, wit, and relaxation, – an exhibition at which men’s eyes have respite from the slaughter of their fellow-men. But it was quite the reverse. The previous combats were the essence of compassion; but now all the trifling is put aside and it is pure murder. The men have no defensive armour. They are exposed to blows at all points, and no one ever strikes in vain. Many persons prefer this programme to the usual pairs and to the bouts ‘by request.’ Of course they do; there is no helmet or shield to deflect the weapon. What is the need of defensive armour, or of skill? All these mean delaying death. In the morning they throw men to the lions and the bears; at noon, they throw them to the spectators. The spectators demand that the slayer shall face the man who is to slay him in his turn; and they always reserve the latest conqueror for another butchering. The outcome of every fight is death, and the means are fire and sword. This sort of thing goes on while the arena is empty. You may retort: ‘But he was a highway robber; he killed a man!’ And what of it? Granted that, as a murderer, he deserved this punishment, what crime have you committed, poor fellow, that you should deserve to sit and see this show? In the morning they cried ‘Kill him! Lash him! Burn him! Why does he meet the sword in so cowardly a way? Why does he strike so feebly? Why doesn’t he die game? Whip him to meet his wounds! Let them receive blow for blow, with chests bare and exposed to the stroke!’ And when the games stop for the intermission, they announce: ‘A little throatcutting in the meantime, so that there may still be something going on!'”

Again, these are not gladiators Seneca is talking about here, but rather criminals and war prisoners sentenced to death in the arena. Nonetheless, descriptions such as Seneca’s seem to be a large part of the reason why many people have come to believe that gladiators always fought to the death.

The famous phrase “Ave Imperator, morituri te salutant!” (i.e. “Hail Emperor, we who are about to die salute you!”) was not spoken by gladiators, but rather, according to the Roman writer Suetonius in his Life of Claudius, by one particular group of criminals and captives of war who had been sentenced to die in the arena by the Emperor Claudius in 52 AD. Suetonius is the only one who mentions the phrase, though, and it was likely only a one-time occurrence, not a customary greeting. It is also possible that Suetonius may have just made the whole saying up, since he has a reputation for not being a very reliable source.

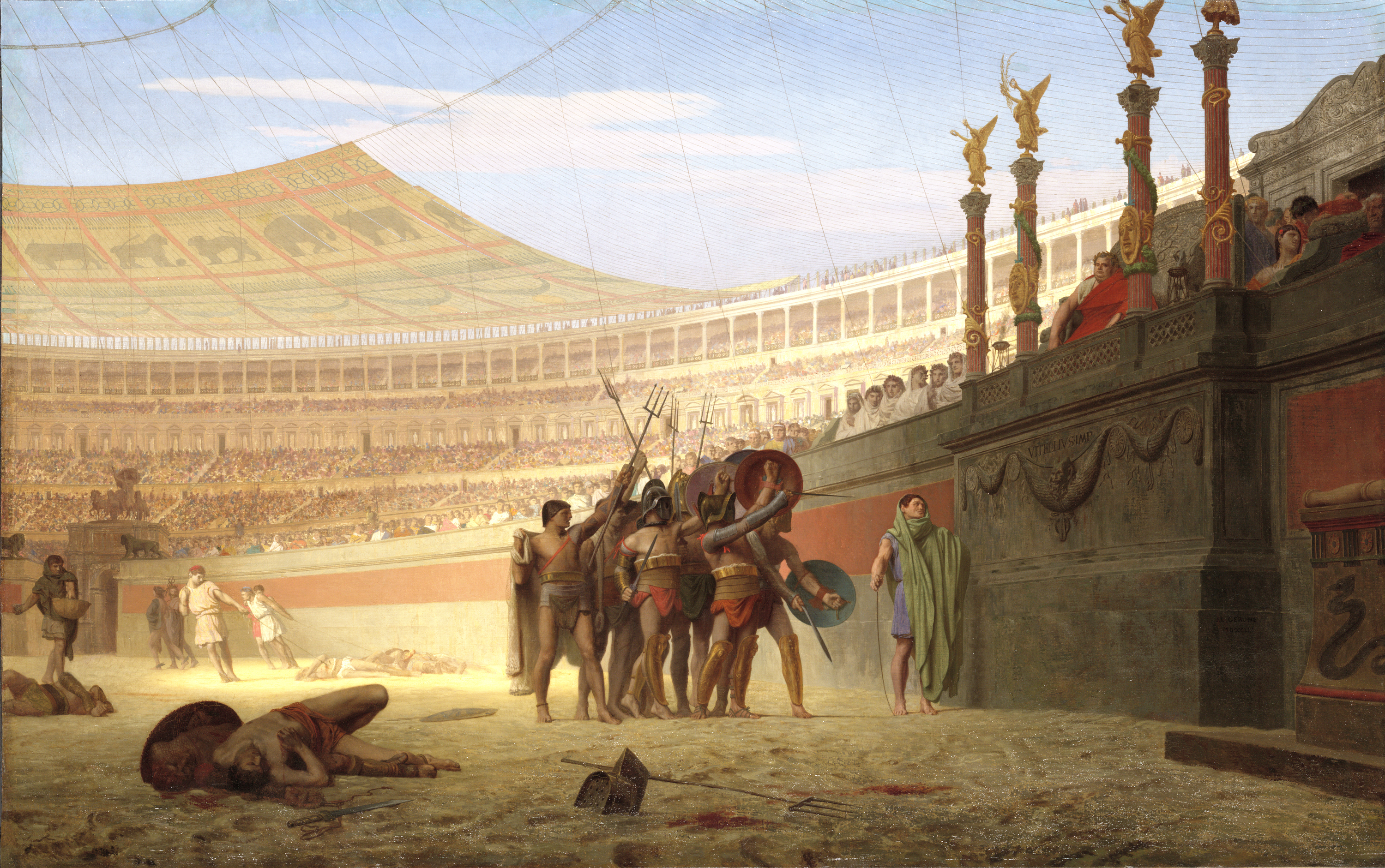

ABOVE: Ave imperator, morituri te salutant, painted in 1859 by the French Academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, depicting gladiators greeting the Roman emperor Vitellius

Misconception #2: When they were not fighting, gladiators were kept locked in filthy cages infested with rodents, were given nothing but gruel to eat, and were provided with nothing but hard stones to sleep on. If they were injured, they were left to die.

This idea, seemingly ubiquitous among modern portrayals of gladiators, is completely false. We admittedly do not know very much about what conditions were like for gladiators on a daily basis, but all the evidence we do have, which comes mostly from archaeology, indicates that gladiators were actually well-fed, well cared-for, and received adequate medical attention. They could even earn enough money to buy their own freedom. Some gladiators who did earn their own freedom still continued to fight, just for the fame and glory.

In fact, in many ways, gladiators were much more like modern celebrity athletes than the brutal killing machines they are portrayed as in Hollywood films. The portraits of famous gladiators decorated public spaces. Roman boys often played with tiny gladiator dolls.

ABOVE: Roman terracotta gladiator dolls dating to the late first century BC

Gladiators could even be sex symbols; for example, a graffito from Pompeii describes one gladiator as “decus puellarum, suspirium puellarum” (“the delight of girls, the sighed-for joy of girls”). Gladiator sweat was sold because it was believed to act as an aphrodisiac. Gladiators even endorsed products! The allure of life as a gladiator was so seductive that the Roman emperor Commodus (ruled 177 – 192 AD) actually fought as one in the arena (although his opponents always intentionally let him win).

ABOVE: Detail of a Roman floor mosaic from the town of Zliten in Libya, dating to the around second century AD, depicting various kinds of gladiators fighting

Misconception #3: Gladiator fights were nothing but people fighting in the arena in hand-to-hand combat.

Ironically, while Hollywood is usually known for exaggerating things, when it comes to the sheer spectacle of Roman gladiator fights, they have actually done the exact opposite: they have completely failed to capture just how insane these fights often were.

In historical reality, gladiator fights were massive public spectacles with so much more than just people fighting in hand-to-hand combat. The Romans were constantly thinking of new and creative ways to make the fights exciting to draw in huge crowds. Gladiators wore elaborate and often outlandish costumes that were usually very loosely based on the actual armor and weapons of various Roman enemies.

There were also different kinds of gladiators, each of which had its own unique costume, weaponry, and fighting style. The Romans enjoyed having different styles of gladiators fight each other to see who would win. Popular interest in gladiator fights was often much more about the different kinds of weapons and fighting styles than about sheer bloodshed and carnage. Everyone had their favorite kinds of gladiator and they would argue about which ones were better, much like how modern sports fans argue about which sports teams are better.

Perhaps the most utterly bizarre kind of gladiator was the retiarius, who fought bare-chested, with a heavily-armored right arm but no other armor whatsoever. He fought with a trident and net as his weapons. Retiarii were known for being small, quick, and light on their feet. Their lack of armor and unconventional weapons meant that they had to be highly trained and highly skilled. It is unclear where idea for the retiarius outfit and fighting style came from, but, by the middle of the first century AD, retiarii had come to dominate the arena.

The retiarius was so dominant in the arena that, from around 50 AD onwards, another kind of gladiator known as a secutor, or “chaser,” began to be specially trained to fight him. The secutor was basically the exact opposite of a retiarius; while the retiarius only wore armor on his left arm and had no shield, the secutor was heavily armored all over and had a large rectangular shield he used to protect himself. While the retiarius was quick and light on his feet, the secutor was slower-moving because he was wearing more armor. While retiarii relied on being highly skilled fighters, secutores relied more heavily on brute strength.

ABOVE: Scene from the Zliten mosaic showing a wounded retiarius surrendering to a secutor

Things got even more fantastical than just outlandish costumes and fighting styles. Gladiators often reenacted famous historical battles in the arena with very elaborate sets, props, and costumes while professional poets recited a poetic account of the battle. You know those “living history” battle reenactments we have today? Those are basically the modern equivalent of these types of gladiator fights, only on a much smaller scale.

Gladiators did not just fight in hand-to-hand combat against other gladiators. Some arenas, including the Colosseum, were designed so they could be filled with water, allowing gladiators to fight naval battles. The late first-century AD Roman poet Martial describes in his On the Public Spectacles 24 the astonishment of a foreigner coming to Rome and seeing a mock naval battle in the Colosseum:

“Whoever you may be, who are here a lately arrived spectator from distant lands, upon whom for the first time has shone the vision of the sacred show,—that the goddess of naval warfare may not deceive you with these ships, nor the water so like to the waves of the sea,—here, awhile since, was the dry land. Do you hesitate to believe it? look on, whilst the waves fatigue the god of war. A short interval, and you will say, ‘Here but a while since was the sea.'”

ABOVE: The Naumaquia, painted in 1894 by the Spanish historical painter Ulpiano Checa, depicting his imagining of a staged naval battle in the Roman Colosseum

Fights between human warriors and wild animals of all sorts were also extremely popular. Officially, gladiators only fought other gladiators, so trained fighters who specialized in fighting wild animals were known as bestiarii.

The more bizarre and exotic the animals were, the more exciting they were and the more likely they were to draw in crowds. We have mentions and portrayals of bestiarii fighting not only lions, but also elephants, hippopotamuses, crocodiles, hyenas, leopards, tigers, wolves, bears, rhinoceroses, ostriches, chimpanzees, and even on at least one occasion a giraffe. These sorts of exotic animals also showcased the might of the Roman Empire.

ABOVE: Detail from the Zliten mosaic showing bestarii fighting various kinds of wild animals, including bears, lions, deer, wild bulls, horses, and leopards

ABOVE: Detail from the Zliten mosaic showing a bestiarius fighting ostriches

ABOVE: Detail of a Roman floor mosaic from Bad Kreuznach, Germany, depicting a bestiarius slaying a bear

ABOVE: Another scene from the Bad Kreuznach mosaic showing a bestiarius slaying a leopard

Misconception #4: Everyone approved of gladiatorial games.

Even in antiquity, many people actually objected to gladiatorial games, seeing them as nothing more than pointless brutality. (You have to remember that, while deaths in the arena were generally not as common as they are portrayed in modern films, they did still happen and, since gladiators always fought with real weapons, non-lethal injuries were very common also.)

The Roman orator Cicero (lived 106 – 43 BC) condemned gladiator fights in a letter written in around 55 BC to his friend Marcus Marius. Cicero writes:

Why, again, should I suppose you to care about missing the athletes, since you disdained the gladiators? in which even Pompey himself confesses that he lost his trouble and his pains. There remain the two wild-beast hunts, lasting five days, magnificent—nobody denies it—and yet, what pleasure can it be to a man of refinement, when either a weak man is torn by an extremely powerful animal, or a splendid animal is transfixed by a hunting spear? Things which, after all, if worth seeing, you have often seen before; nor did I, who was present at the games, see anything the least new. The last day was that of the elephants, on which there was a great deal of astonishment on the part of the vulgar crowd, but no pleasure whatever. Nay, there was even a certain feeling of compassion aroused by it, and a kind of belief created that that animal has something in common with mankind.

While Cicero certainly had disdain for the games, Seneca the Younger, in the passage I quoted towards the beginning of this article, expressed intense, visceral revulsion towards them. Later Christian writers outright deplored them as bloody and immoral.

The early Christian writer and theologian Tertullian (lived c. 155 – c. 240 AD), a North African of Berber origin who wrote in Latin, condemned gladiatorial games in the strongest possible terms in Chapter XIX of his treatise On the Spectacles, as translated by Reverend S. Thelwall:

“We shall now see how the Scriptures condemn the amphitheatre. If we can maintain that it is right to indulge in the cruel, and the impious, and the fierce, let us go there. If we are what we are said to be, let us regale ourselves there with human blood. It is good, no doubt, to have the guilty punished. Who but the criminal himself will deny that? And yet the innocent can find no pleasure in another’s sufferings: he rather mourns that a brother has sinned so heinously as to need a punishment so dreadful. But who is my guarantee that it is always the guilty who are adjudged to the wild beasts, or to some other doom, and that the guiltless never suffer from the revenge of the judge, or the weakness of the defence, or the pressure of the rack? How much better, then, is it for me to remain ignorant of the punishment inflicted on the wicked, lest I am obliged to know also of the good coming to untimely ends–if I may speak of goodness in the case at all! At any rate, gladiators not chargeable with crime are offered in sale for the games, that they may become the victims of the public pleasure. Even in the case of those who are judicially condemned to the amphitheatre, what a monstrous thing it is, that, in undergoing their punishment, they, from some less serious delinquency, advance to the criminality of manslayers!”

The later Christian writers Lactantius (lived c. 250 – c. 325), John Chrysostom (lived c. 349 – 407 AD), and Augustine of Hippo (lived 354 – 430 AD) also condemned the gladiatorial contests as heinous and immoral.

Eventually, after Rome converted to Christianity, gladiatorial games were outlawed entirely. In 399 AD, the Emperor Honorius closed the schools for gladiators and, in 404 AD, he banned gladiator fights entirely, bringing an end to the centuries-long history of the games.

Misconception #5: Gladiator games were the most popular form of public entertainment in ancient Rome.

Despite their disproportionate prominence in modern films and television, gladiator fights were actually never the most popular form of public entertainment in ancient Rome. For one thing, the Colosseum itself, the largest arena of its kind, could only seat roughly 50,000 people, which means that only around five percent of the estimated one million people living in the city of Rome at its height could even fit in it when it was completely full.

Additionally, many of the seats in Colosseum were reserved for specific people, such as the emperor, Senators, Vestal Virgins, and other prominent individuals. These seats were reserved, regardless of whether the people they were reserved for actually came to the show or not, meaning that the actual number of people able to attend any given gladiatorial match must have been considerably lower than the number of people who could conceivably fit into the seating area of the Colosseum.

The Circus Maximus, the horse-racing stadium in the city of Rome, could hold more than twice as many people as the Colosseum. The ancient Romans, much like architects today, designed seating areas based on how many people they thought the area would need to be able to hold. Therefore, the fact that the Circus Maximus could seat twice as many people as the Colosseum would seem to indicate that horse and chariot races were roughly twice as popular as gladiatorial games.

Strangely, though, we see far more depictions of gladiators in modern popular culture than horse races, perhaps because people today find horse and chariot races less exciting than the idea of slaves being forced to fight each other to the death for popular amusement. The irony is that we so often think of the ancient Romans as being so barbaric, yet we are the ones who have the disproportionate fixation with gladiator fights.

ABOVE: Imaginative painting of what the Circus Maximus might have looked like at its height from around 1638, painted by the Italian painters Viviano Codazzi and Domenico Gargiulo

Misconception #6: A “thumbs-down” from the editor, the authority supervising the match, meant a fallen gladiator was supposed to die and a “thumbs-up” meant he would be allowed to live.

While it is true that, during some events, the editor could signal to a gladiator to kill his fallen opponent, the signal to do this was not a “thumbs down” gesture. This misconception arises from a mistranslation of the Latin phrase pollice verso, which literally means “with a turned thumb.” Scholars debate exactly what this phrase means, but it probably did not mean a “thumbs down.” Instead, it probably referred to some kind of thumb-to-the-side gesture.

Likewise, the sign for a gladiator to spare his opponent was not a “thumbs up,” but rather a closed fist (pollice compresso; “with a compressed thumb”). The only reason why the “thumbs up” gesture has become so widely believed to have been the sign used to indicate a gladiator could live is probably because of the gesture’s prominence in our own culture today.

Summary

I know I have covered a lot in this post, so here is a quick recap of the main points:

- In the Roman Empire, gladiators did not always, or even usually, fight to the death. Gladiators were a major investment for their owners and the supply of gladiators was vastly lower than the demand for gladiator fights. Therefore, measures were taken to try to ensure that gladiators, especially popular ones, lasted as long as possible. Some gladiators did die sometimes and gladiatorial combat was certainly not a bloodless sport, but the massive death toll usually portrayed in Hollywood films is greatly exaggerated.

- Gladiators, far from being brutally mistreated, were given the best food and medical care available and the more popular ones were treated by the Roman people like major celebrities.

- Gladiators fights were massive spectacles. Gladiators often wore outrageous costumes and had distinctive fighting styles. They were not always just two people fighting in hand-to-hand combat either; there were also naval fights, reenactments of major historical battles, and fights with all kinds of wild animals captured from all over the Old World.

- Not everyone approved of gladiator fights. Many people, especially early Christians, saw gladiator fights as heinous and immoral.

- Gladiatorial games, despite their disproportionate influence in modern popular culture, were never the most popular form of public entertainment in ancient Rome.

- A “thumbs-down” was not the sign for a gladiator to kill his opponent, nor was a “thumbs-up” a sign for him to let him live.

Thank you for clarifying these blood sports. While I accept all the facts, I wanted to propose a thought experiment: if someone gossipy like Suetonius were the only source to talk about naval battles in the Colosseum, would we believe him, or dismiss it? Because it’s still a little hard to get my head around it: the labor, the cost, the time involved in flooding the arena (and preventing leaks!), then draining it later and restoring it to normal use, and all without modern equipment.

Naval battles in the Colosseum were definitely a real thing. We have numerous ancient sources that refer to them and I believe there is also archaeological evidence from the Colosseum itself that shows it was designed so it could be filled with water.

Right. I said I accept that. My point was that if a semi-reliable source were *the only source,* would we be tempted to dismiss is as apocryphal because it seems hard to believe?