We are all familiar with joke books in some form or another, but did you know that the oldest surviving one was written around 1,600 years ago? It is called Philogelos (Φιλόγελως; Philógelōs), which means “The Laughter-Lover” in Ancient Greek. It was probably written in the late fourth or early fifth century AD and contains 265 jokes written in a crude dialect of Ancient Greek.

Authorship of the Philogelos

The authorship of the collection is uncertain and it has been attributed to a variety of different people. The most complete surviving manuscript of it credits two authors named “Hierokles and Philagros the grammatikos.” Grammatikos could mean “scribe” or possibly “grammarian,” but the grammar of the Philogelos is generally poor, which seems to rule out any possibility that it was written by a trained scribe.

It seems more likely that Philagros was simply a well-known scholar (probably without much of a sense of humor), whose name was tacked onto the collection to lend it a greater verisimilitude of literary importance. Other manuscripts only list “Hierokles” as the author. The Souda, a tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia preserving information from a broad number of classical texts that have since been lost, attributes the Philogelos to a man named “Philistion.”

ABOVE: First page of an early printed edition of the Souda encyclopedia written in Greek. The Souda attributes Philogelos to someone named “Philistion.”

ABOVE: First page of an early printed edition of the Souda encyclopedia written in Greek. The Souda attributes Philogelos to someone named “Philistion.”

Personally, I suspect that the collection was originally anonymous and all of the claimed authors are, in fact, later misattributions. It was extremely common for copyists of anonymous texts to attribute the work they were copying to a famous scholar, even when the work obviously could not have been written by him. For instance, the Fabulae is one of only two surviving works of classical mythography (the other being the Bibliotheke of Pseudo-Apollodoros). The only surviving manuscript of it, which has since been destroyed, credited a certain “Hyginus” as the author. Presumably this was meant to refer to Gaius Julius Hyginus, a renowned grammarian who had served as the superintendent of the Palatine Library in Rome during the reign of Emperor Augustus. We now know, however, for a variety of reasons, that the Fabulae could not have possibly been written by him.

Other known joke books from antiquity

Although the Philogelos is the oldest surviving joke book, it is far from the oldest known joke book. According to the second-century AD Greek writer Athenaios of Naukratis in his book Wise Men at Dinner, King Philippos II of Makedonia (ruled 359–336 BC), the father of Alexander the Great, had requested for an Athenian social club to write down all of its members’ funniest jokes and send them to him. This collection of jokes and witty sayings described by Athenaios has not survived to the present day and, in all likelihood, had already been lost for centuries by the time Athenaios was writing. Nonetheless, it is still the oldest known joke book.

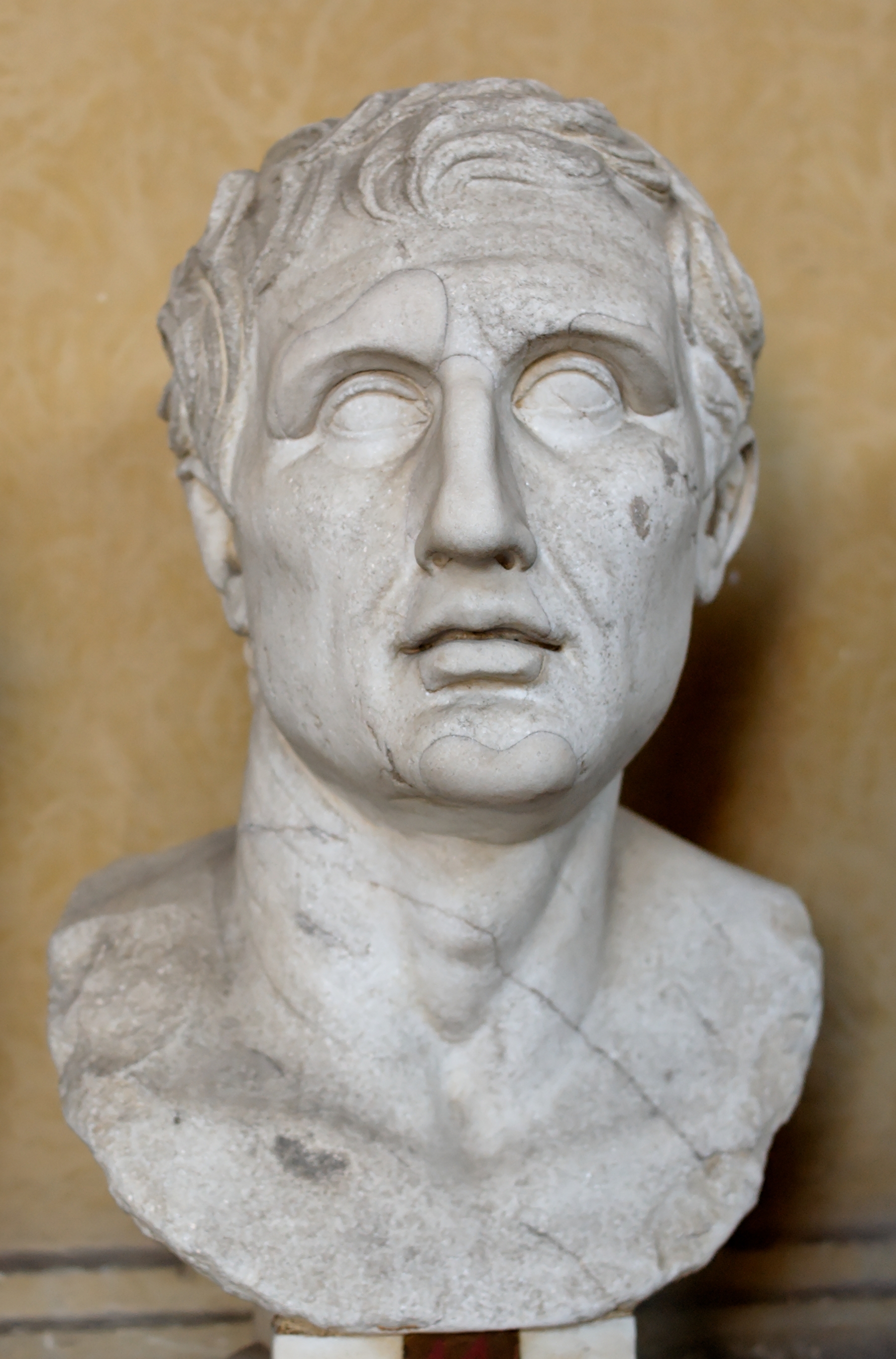

ABOVE: Marble head of King Philippos II of Macedonia, said by Athenaios to have commissioned the writing of what is now the oldest known jokebook to have existed

Other joke books are also known to have existed in antiquity. For instance, the Roman playwright Plautus (lived c. 254 – 184 BC) has his characters mention the existence of joke books on two separate occasions. This seems to indicate that such books would have been relatively well-known and commonplace.

Style and purpose of the Philogelos

The actual j0kes in the Philogelos rely heavily on stereotypes and stock characters, much like modern “dumb blond” jokes, but the stereotypes in the jokes are frequently foreign and unrecognizable to modern readers: an “absent-minded professor,” a sharp-witted cynic who spits off one-liners, a eunuch, a man with a hernia, a man with bad breath, men from the cities of Kyme, Abdera, and Sidon, a miser, and a grumpy old man.

This style of humor seems to reveal an affinity between the Philogelos and New Comedy, the style of classical comedy which originated in Athens during the mid-fourth century BC and later spread to Rome, remaining the dominant style of comedy throughout the remaining portion of the classical era. Like the Philogelos, but also similar to a modern sitcom, New Comedy relied heavily on stock characters, stereotypes, and situational irony.

The most famous representative of New Comedy and the only Greek exponent of the genre for whom any plays have survived in a nearly complete state is the Athenian playwright Menandros (lived c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC). Two of Menandros’s comedies have survived to the present day nearly complete: The Grumpy Old Man and The Girl from Samos, both of which are named after the stereotypes which the titular characters embody.

Interestingly, the “grumpy old man” stereotype recurs in the Philogelos, suggesting that it remained a common stereotype for the roughly 800 years that passed between Menandros and late antiquity. Even today, this stereotype still seems to abide, at least in some quarters.

ABOVE: Roman marble copy of a late fourth-century BC Greek bust of Menandros

As for the purpose of the Philogelos, it probably was not intended as a joke book we might be familiar with today, meant to be read straight through. Instead, according to British classical scholar Mary Beard, it was probably intended more as a “jokester’s handbook” of witty anecdotes to memorize and retell whenever an appropriate opening in conversation presented itself.

Examples of jokes from the Philogelos

Here are a few samples of some of the better jokes in the collection:

#43. When an intellectual was told by someone, “Your beard is now coming in,” he went to the rear-entrance and waited for it. Another intellectual asked what he was doing. Once he heard the whole story, he said: “I’m not surprised that people say we lack common sense. How do you know that it’s not coming in by the other gate?”

#57. An intellectual got a slave pregnant. At the birth, his father suggested that the child be killed. The intellectual replied: “First murder your own children and then tell me to kill mine.”

#115. An Abderite saw a eunuch talking with a woman and asked him if she was his wife. When he replied that eunuchs can’t have wives, the Abderite asked: “So is she your daughter?”

#187A. A rude astrologer cast a sick boy’s horoscope. After promising the mother that the child had many years ahead of him, he demanded payment. When she said, “Come tomorrow and I’ll pay you,” he objected: “But what if the boy dies during the night and I lose my fee?”

#234. A man with bad breath asked his wife: “Madame, why do you hate me?” And she said in reply: “Because you love me.”

#263. Someone needled a jokester: “I had your wife, without paying a dime.” He replied: “It’s my duty as a husband to couple with such a monstrosity. What made you do it?”

More examples of jokes from the collection can be found here.