We have all heard that our country was founded on the idea that “all men are created equal.” That is certainly what Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Unfortunately, ideas are often quite different from actions. The vast majority of the Founding Fathers of the United States of America owned slaves and, for many of them, their public statements stood in stark contrast with their own private actions and beliefs. Nonetheless, their views on the issue of slavery were actually quite diverse and many of them changed their views on the subject over the courses of their lives. In this article, we will examine the unvarnished truth of some of the major Founding Fathers’ views on slavery.

Benjamin Franklin

In his younger days, Benjamin Franklin (lived 1706 – 1790) was a slave-owner himself. He also published wanted posters for runaway slaves in his newspaper. To his credit, though, Franklin did also publish a series of anti-slavery tracts written by the Quaker Ralph Sandiford. This, however, does not necessarily indicate that Franklin at this point in his life was opposed to slavery, since he often printed views he did not agree with.

As he grew older, Benjamin Franklin became increasingly jaded about the institution of slavery. He eventually became a stalwart abolitionist and spent the final years of his life actively campaigning against slavery. Unfortunately, at least initially, his motives for wanting to abolish slavery were not particularly progressive; in fact, he did not care about blacks’ wellbeing at all. Instead, he argued that slavery needed to be abolished because it made white people lazy.

Franklin argued that having slaves to do all their work for them would cause white people to become less willing to do things for themselves. In one essay written in 1751, Franklin warned: “Slaves also pejorate the Families that use them; the white Children become proud, disgusted with Labour, and being educated in Idleness, are rendered unfit to get a Living by Industry.” He repeatedly referred to people with black skin using racist language and at one point called all blacks “sullen, malicious, and revengeful.”

Finally, in the last few years of his life, Franklin finally seems to have come to the conclusion that black people, like all other people, deserved to be free. He wrote a letter to the Pennsylvania Assembly arguing that extra funds should be put towards aiding in the betterment of free blacks and, in February of 1790, only two months before his death, he even wrote a letter to Congress arguing for the abolition of slavery on the grounds that it was hypocritical for Americans to speak of “equal liberty” while blacks “…in this land of Freedom are degraded in to perpetual Bondage, and who amidst the general Joy of Surrounding Free men are groaning in servile subjection…” Unfortunately, the letter was never given much attention and Benjamin Franklin died two months after it was written.

ABOVE: Portrait of Benjamin Franklin from around 1785 by Joseph Duplessis. Although he himself had once owned slaves, Franklin became a strong proponent of abolitionism in his later years.

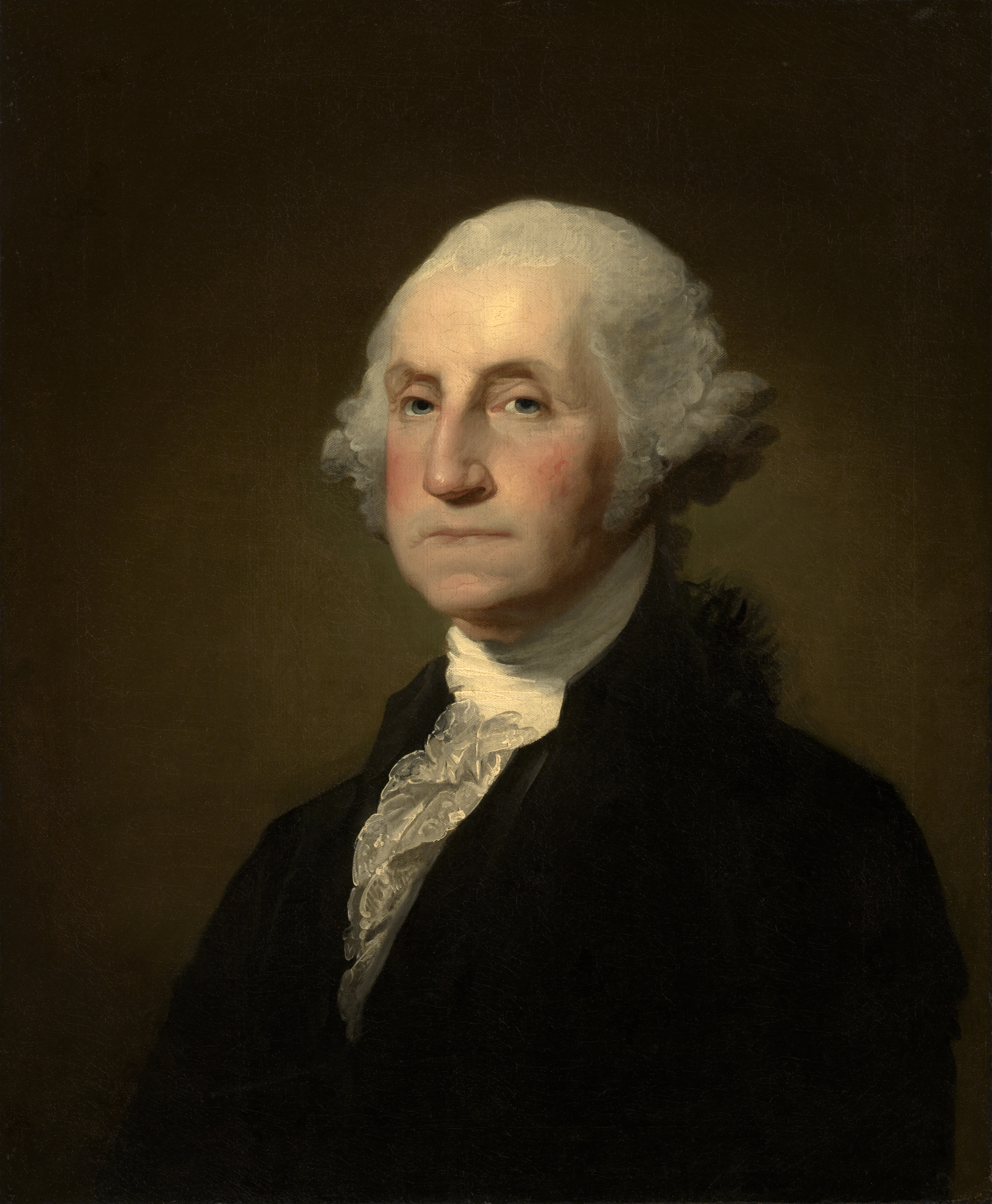

George Washington

George Washington (lived 1732 – 1799), the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and first president of the United States under the Constitution, was a lifelong slave-owner. In fact, George Washington owned no less than 317 slaves at the time of his death. His ownership of slaves began when his father died when he was only elven years old, leaving him with ten slaves.

If George Washington ever had any doubts about the morality of slavery, he never expressed them in writing. Nonetheless, somewhat surprisingly, George Washington posthumously set all of his slaves free in his will, making him the only American president ever to set all of his slaves free.

Accounts of General Washington’s treatment of his slaves vary wildly. Richard Parkinson, one of Washington’s neighbors, wrote that more Washington treated his slaves “…with more severity than any other man.” Contrarily, however, one foreign visitor to Washington’s plantation remarked that Washington treated his slaves “…far more humanely than do his fellow citizens of Virginia.”

The rumors that George Washington once had an affair with one of his slaves are completely false; in fact, there is currently absolutely no evidence whatsoever to indicate that George Washington ever partook in any kind of marital infidelity.

ABOVE: Portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart from 1797. Washington owned hundreds of slaves over the course of his lifetime, although he did set all of them free after his death in his will.

Thomas Jefferson

Like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson (lived 1743 – 1826), the author of the Declaration of Independence and third president of the United States, was a slave-owner for his entire adult life. Hypocritically, despite the fact that he himself owned slaves, Jefferson authored numerous treatises in which he unambiguously condemned slavery as immoral. He deplored slavery as a “moral depravity,” an “abominable crime,” and a “hideous blot.” He even claimed that it was the greatest threat to fledgling American democracy.

Jefferson supported the gradual abolition of slavery, believing that slavery could not simply be abolished all at once. Like many of the other Founding Fathers, Thomas Jefferson believed that slavery would eventually die out on its own without any form of government intervention.

Yet, somehow, even as he wrote these things, Jefferson himself still owned over 600 slaves at his plantation at Monticello, located just outside Charlottesville, Virginia. In fact, Jefferson himself only ever set a few slaves free over the course of his entire lifetime. Unlike Washington, Jefferson did not even set his slaves free in his will.

Furthermore, Jefferson also firmly believed that black people were inherently inferior to white people, at one point calling them “as incapable as children.” He insisted that, once they were freed, all blacks would need to be deported back to Africa so that the United States would be able to become a racially homogenous society.

It is true that, after the death of his wife Martha in 1782, Thomas Jefferson did engage in a long-term sexual relationship with her half-sister, his slave Sally Hemings. At first, the historical evidence to support the affair was rather scanty. Jefferson is said to have treated Sally Hemings’s children with special favoritism and even set them free once they were fully grown. In fact, the only slaves he ever freed in his entire life were all Hemingses. Furthermore, all the Hemings children were said to have been especially pale-skinned in contrast to Jefferson’s other slaves. Sally Hemings was said to have been exceedingly beautiful and she is said to have born a strong resemblance to her half-sister Martha Jefferson.

ABOVE: A lewd political cartoon from c. 1804, mocking Thomas Jefferson’s notorious affair with his slave Sally Hemings

All of Sally Hemings’s children were born during the period when Jefferson and her were together. In his Farm Book, Thomas Jefferson seems to have intentionally omitted the name of the father of Sally Hemings’s children, but kept meticulous records of the names of the fathers of all his other slaves. Finally, even though one of his political opponents publicly claimed in 1802 that Jefferson had had relations with Sally Hemings, Jefferson himself never publicly denied the allegation.

For years, historians dismissed the alleged affair as nothing but a piece of anti-Jefferson propaganda. The affair, however, began to gain credibility in the mid-twentieth century. Then, in 1998, a DNA test revealed that there was indeed a genetic connection between the patrilineal Jefferson line and Sally Hemings’s youngest son, Eston Hemings, who was born at Monticello in 1808. Since the results of the DNA test were made public, most scholars have come to accept that Eston Hemings was indeed Thomas Jefferson’s son.

ABOVE: Portrait of Thomas Jefferson from 1800 by Rembrandt Peale. Jefferson railed against slavery in numerous treatises, condemning it as immoral, yet he himself owned over 600 slaves and only ever set a handful of them free.

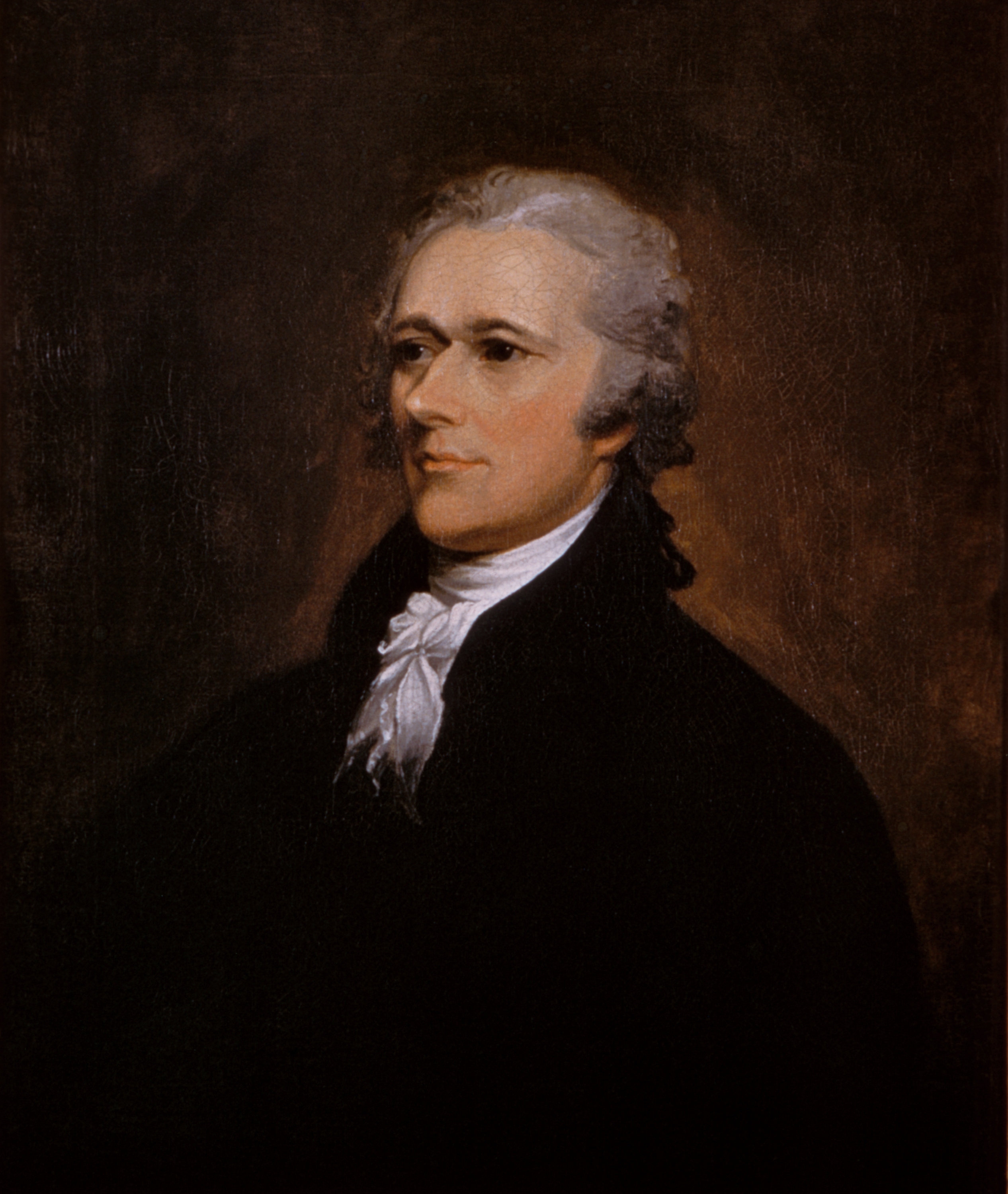

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (lived 1755 or 1757 – 1804), the author of fifty-one of The Federalist Papers and first Secretary of the Treasury of the United States, has been portrayed by modern biographers and by popular culture as something of an abolitionist icon. Unfortunately, the truth does not live up to the legend; in historical reality, Hamilton’s views were not nearly so progressive as many of his biographers have asserted.

For one thing, it is highly probable, although not certain, that Alexander Hamilton actually owned slaves himself. There are several entries in his personal financial records that seem to indicate him having purchased slaves. Furthermore, his own grandson Allen McLane Hamilton testified: “It has been stated that Hamilton never owned a negro slave, but this is untrue. We find that in his books there are entries showing that he purchased them for himself and for others.”

Additionally, in 1780, Hamilton married into the Schuyler family, one of the most prominent slaveholding families in New York. If he had really been an ardent abolitionist like his biographers (not to mention to popular musical Hamilton) portray him, he would have certainly objected the Schuylers’ ownership of slaves. Instead, however, he never raised any protests whatsoever about their slaveholding status and even seems to have taken pride in the fact that he was married into a family that was wealthy enough to own slaves.

At the same time, however, Alexander Hamilton was a member of the New York Society for the Promotion of the Manumission of Slaves. This, however, proves very little. The Society was a comparatively moderate organization, which allowed its members to remain slaveholders. It is probable that the only reason Hamilton joined the society to begin with was because many members of the group were New Yorkers of high status and Hamilton likely saw it as simply an occasion to rub elbows with members of the wealthy elite.

In any case, all that the Society actually advocated was that people ought to free their own slaves, not that they should be required by law to do so. The society supported “manumission,” not abolition. Finally, although Hamilton was actively involved in the Society, his attendance at their meetings was infrequent and he seems to have seldom discussed his involvement in the society with non-members.

In 1779, Hamilton supported a plan proposed by his friend John Laurens that would allow slaves to join the Continental Army and be granted their freedom in exchange. On 14 March, Hamilton wrote a letter to John Jay defending Laurens’s plan. For the most part, he defends the plan from a strategic standpoint, arguing that it would give the Continental Army an advantage. He does, however, briefly say that he supports the plan partly out of sympathy for the enslaved black people who could gain their freedom from it:

“An essential part of the plan is to give them their freedom with their muskets. This will secure their fidelity, animate their courage, and I believe will have a good influence upon those who remain, by opening a door to their emancipation. This circumstance, I confess, has no small weight in inducing me to wish the success of the project; for the dictates of humanity and true policy equally interest me in favour of this unfortunate class of men.”

For more information about Alexander Hamilton’s views on slavery, you can read this article I wrote about him.

ABOVE: Portrait of Alexander Hamilton from 1805 by John Trumbull. Hamilton’s alleged support of abolitionism has been greatly exaggerated by modern biographers and by popular culture.

John Adams

The only major Founding Father who is known for certain to have never owned a single slave is John Adams (lived 1735 – 1826), the second president of the United States under the Constitution. John Adams viewed slavery as undeniably wrong and immoral, but he was nonetheless strongly opposed to the idea of immediately abolishing it. Like Jefferson and Hamilton, Adams supported the gradual, voluntary manumission of slaves by own their masters, without government interference.

On January 24, 1801, John Adams wrote a letter to Church Churchman and Jacob Lindley, two abolitionists who had mailed him an abolitionist tract written by the Quaker abolitionist writer Warner Mifflin (lived 1745 – 1798). This letter is perhaps the most explicit statement of John Adams’s long-held stance on the issue of slavery. In the letter, John Adams explains that he has always detested slavery and regarded it as a moral abomination, but that he regards abolitionists like Mifflin as “…produc[ing] greater violations of Justice and Humanity, than the continuance of the practice [of slavery itself].”

In other words, John Adams says in the letter that, although he has always hated slavery, he hates abolitionists even more and sees the movement for the immediate abolition of slavery as an even greater threat to liberty and human rights than slavery itself. This notion seems absolutely bizarre to most people today. How on earth could wanting to free all slaves be seen as a greater threat to liberty and human rights than slavery?

Well, John Adams, like virtually all of the other Founding Fathers, firmly believed in the inalienable right of every free man to his own property. Slaves were property; they belonged to their masters. From John Adams’s viewpoint, forcing all masters to free their slaves would have meant depriving them of their natural right to their own property. This was far from a minority viewpoint among northerners at the time. Indeed, at the time, abolitionists were widely seen as dangerous and subversive radicals seeking to maliciously deprive men of their natural rights to their own properties.

Nonetheless, John Adams vehemently emphasizes in the letter, “I have always employed freedmen, both as Domesticks and Labourers, and never in my Life did I own a Slave.” Like Thomas Jefferson, John Adams wrongly believed that slavery would simply eventually die out on its own without the government having to intervene. In the letter, he states that “[t]he Abolitionism of Slavery must be gradual and accomplished with much caution and circumspection.”

ABOVE: Portrait of John Adams by Gilbert Stuart. Adams was one of the few Founding Fathers who never owned slaves, but he was nonetheless strongly opposed to abolitionism.

Summary

Of the major Founding Fathers—the ones most of us can immediately name off the tops of our heads—all of them but John Adams owned slaves at some point in their lives. Of them, only Benjamin Franklin at the very end of his life could accurately be called an ardent abolitionist and, even then, at least initially, his reasoning for wanting slavery abolished seems to have been motivated more out of concern for white people’s laziness than for the wellbeing of the slaves themselves.

Washington and Jefferson, as wealthy Virginia plantation-owners, owned hundreds of slaves and both set very few of them free during their own lifetimes, although Washington did set all of his slaves free in his will. Even Alexander Hamilton was far from the abolitionist hero he is portrayed as by modern biographers and by popular culture and, in all likelihood, he probably owned at least a few slaves himself.

I am not writing this article to make the Founding Fathers out to be horrible people; on the contrary, I think that they did many great and admirable things. Nonetheless, I do wish to remind everyone that they were not gods, but rather very deeply flawed human beings who were guilty of more than a little hypocrisy when it came to writing about human rights.

ABOVE: Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States, painted in April 1940 by Howard Chandler Christy, depicting the artist’s romanticized vision of what the signing of the United States Constitution in Independence Hall in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787 might have looked like

FURTHER READING

https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/franklin

http://www.austincc.edu/history/cronin.html

http://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/slavery/

http://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/slavery/ten-facts-about-washington-slavery/

https://www.monticello.org/site/plantation-and-slavery/thomas-jefferson-and-slavery

http://www.umbc.edu/che/tahlessons/pdf/historylabs/Where_Did_Thomas_Jefferson_Stand_on_the_Issue_of_Slavery.PrinterFriendly.pdf

https://www.monticello.org/site/plantation-and-slavery/thomas-jefferson-and-sally-hemings-brief-account

http://www.history.com/topics/sally-hemings

https://www.varsitytutors.com/earlyamerica/early-america-review/volume-15/hamilton-and-slavery

https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/early-republic/resources/john-adams-abolition-slavery-1801

IMAGE CREDITS

The featured image for this article is an illustration from 1832 depicting slaves unloading ice in Cuba. This image is in the public domain in the United States of America. This image was retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

One thing the artical makes clear is that poblic figures of early Amirica attained to a level of rhetorical literacy that is unmatched today. For instance, the diction fallacy whereby we are to believe that jadedness about slave ownership is tantanount to opposition to that institution!